Caribbean to Get Tsunami Warning System as Scientists Fret

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Last month's tsunami-causing earthquake in Indonesia has scientists exploring seafloors and fault lines in an effort to predict where and when a similar disaster could occur. While it is unlikely that such a catastrophe will strike the Atlantic Coast of the United States, there is growing concern that a series of earthquakes could trigger tsunamis in the Caribbean.

Meanwhile, the U.S. government today outlined plans to expand its Pacific tsunami warning system to the Caribbean, as well as the Gulf of Mexico and even the Atlantic.

On average, a major earthquake shakes the Caribbean every 50 years. A dozen earthquakes of magnitude 7.0 or greater have occurred in the last 500 years, each capable of creating a tsunami. Most recently, in 1946, a magnitude 8.1 earthquake produced a tsunami that killed a reported 1,600 people.

The clockwork-like nature of this area has scientists asking when, not if, another tsunami will strike.

In a study published Dec. 24, 2004 in the Journal of Geophysical Research, geologists Uri ten Brink of the U.S. Geological Survey in Woods hole and Jian Lin of the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution report that the danger of tsunami causing earthquakes in the Caribbean should be taken seriously and call for the implement of better warning systems.

"The threat of major earthquakes in the Caribbean, and the possibility of a resulting tsunami, are real even though the risks are small in the bigger picture," said ten Brick, adding, "It has happened before, and it will happen again."

The danger lies at the bottom of two undersea trenches, the Hispaniola Trench and the Puerto Rico Trench, which at 27,362 feet below sea level is the deepest point in the Atlantic Ocean. Both trenches create what are called subduction zones, where an oceanic plate collides and sinks below a continental plate. Because these two trenches are deep and seismically active, they are ripe for producing tsunamis.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Hispaniola is at double the risk of this type of natural disaster. In addition to the offshore Hispaniola Trench, the Septentrional fault zone, which runs through the highly populated Cibao valley in the Dominican Republic, is also capable of producing strong earthquakes. Heavy activity in one fault zone could start a chain reaction in the neighboring zones, causing even more destruction.

"Our results indicate that great subduction zone earthquakes, which often occur in the deep trenches off shore, have the potential to add stress or trigger earthquakes on other types of faults on the nearby islands," said Lin.

While the Atlantic Coast is relatively risk free, the same cannot be said for the Pacific Northwest. The Cascadian subduction zone, a 680-mile fault line that runs 50 miles offshore from Northern California to Southern British Columbia, is geographically similar to the Caribbean trenches, except its quakes are much more powerful. In an earlier article, scientists speculated that the entire fault line could rupture simultaneously, causing a magnitude 9.0 earthquake and tsunamis like those seen in Indonesia.

The lead wave of the Indonesian tsunami traveled at 500 mph. Should the Puerto Rico Trench, which runs parallel to Puerto Rico's coast line a mere 75 miles offshore, produce a similar wave, it could reach land in less than 10 minutes. Early warning systems could provide residents a short, but crucial, window of time to prepare for the worst.

"We don't want people to overreact, just make them aware of the potential risk of such rare and yet deadly events so they are prepared," said Lin.

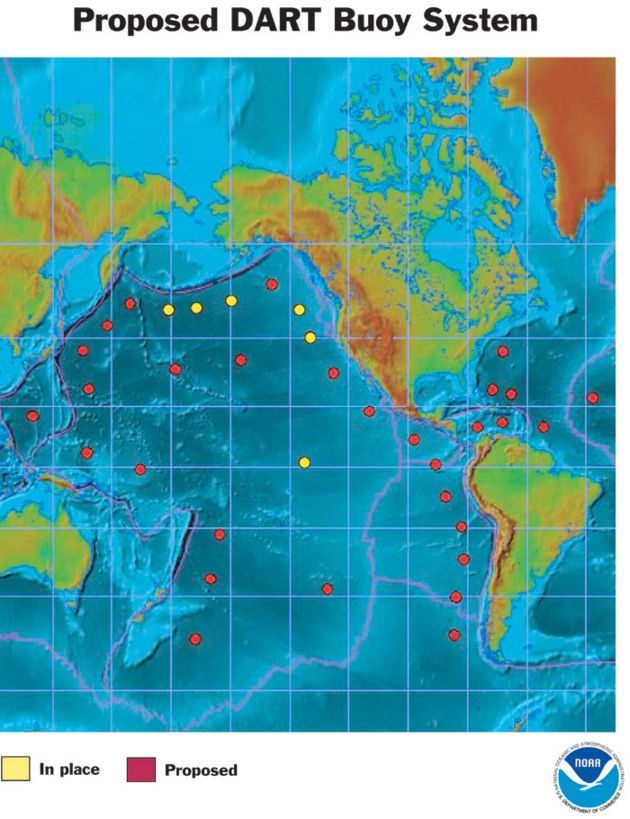

U.S. officials announced Friday that the existing Pacific tsunami detection and warning system would be expanded to cover a broader range of the Pacific, and it will be extended to include the Caribbean, the Gulf of Mexico, and areas of the Atlantic that could affect the U.S. coast.

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) will deploy 32 new buoys for a fully operational, broader tsunami warning system by mid-2007. The total cost is $37.5 million.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus