How did Earth get its name?

It has an Anglo-Saxon origin, but the story gets complicated.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

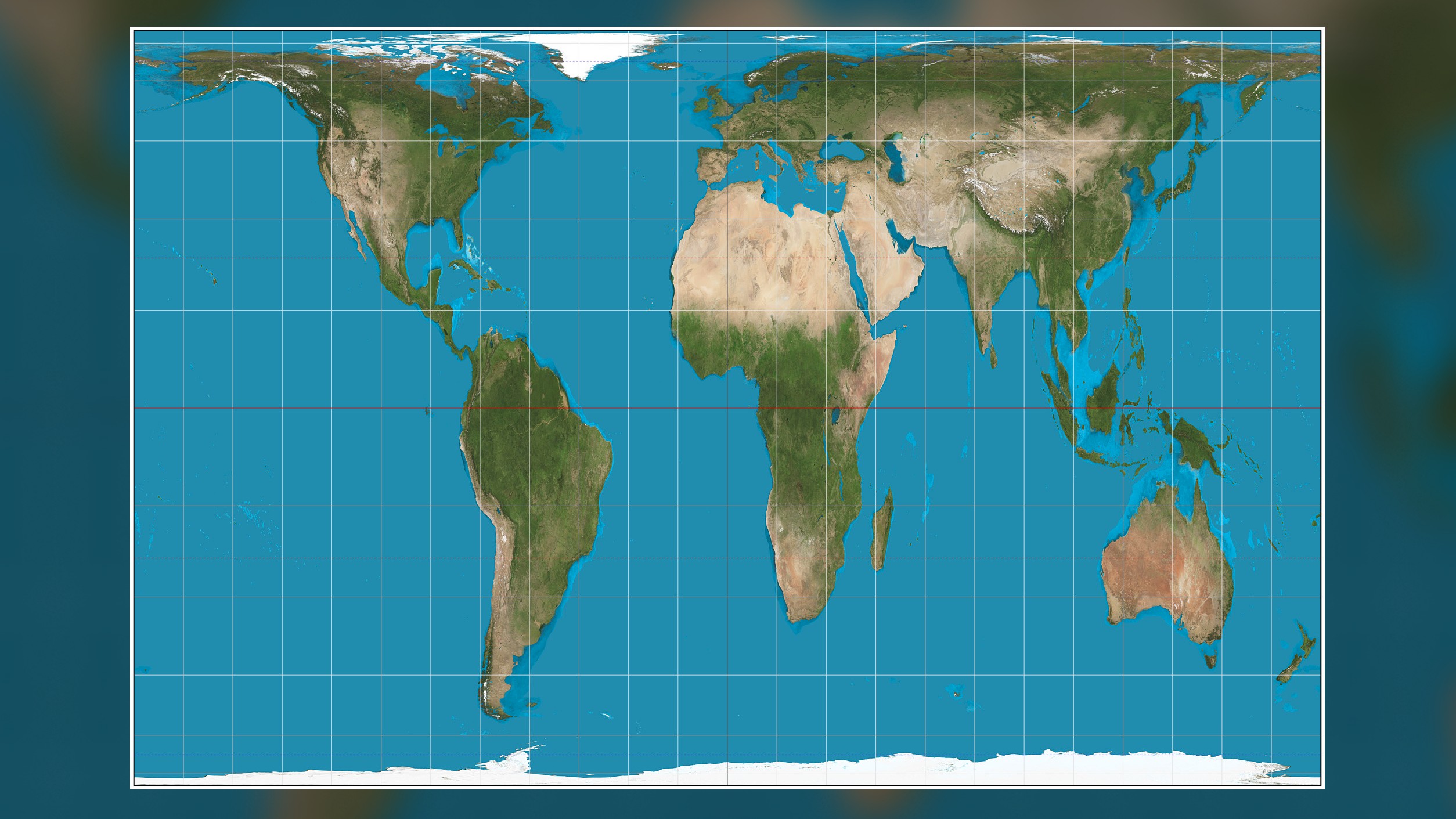

Whether you call our planet the Earth, the world or a terrestrial body, all of these names have an origin story deep in history.

Like many names of solar system objects, Earth's original namer is long lost to history. But linguistics provide a few clues. Ertha is an approximate spelling for "the ground" (meaning, the ground upon which we stand) in Anglo-Saxon, one of many ancestor languages to English.

"Anglo-Saxon" is a modern term to refer to a cultural group who lived within modern-day England and Wales shortly after the Roman Empire collapsed, between the fifth century and the Norman Conquest of 1066.

The identities of people were complex, and different individuals likely had different associations depending on their family, their history and the land upon which they lived, scientists say. Ertha, like the other names to represent our planet and other ones, must be understood in this context.

Related: What would happen if Earth suddenly stopped spinning?

Ertha in Anglo-Saxon "means the ground on which you walk, the ground in which you sow your crops," said freelance archaeologist and historian Gillian Hovell, who is known as "The Muddy Archaeologist."

Ertha also links to a place in which life emerges and perhaps even to the ancestors who are buried in the ground, Hovell said. But sometimes the name can change its meaning depending on the culture.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Other modern popular terms for "Earth" come from Latin. Terra means land — again, the land on which you are standing, farming or otherwise interacting with, Hovell said. That's where we get the modern-day English words "terrestrial," "subterranean," "extraterrestrial" and so forth.

Orbis was used when authors wanted to talk about Earth as a globe. "They knew it was a globe," Hovell said of the ancient Romans, who closely followed Greek science; the Greek Eratosthenes measured our planet's circumference in 240 B.C.

"It was a globe of lands," Hovell said of the orbis meaning; orbis is the root word of the modern-day "orbit." There was yet another term, mundus, which was meant to describe the whole of the universe.

"The world is everything that contains us [humans], but it was quite obviously separate from the planets," Hovell said of mundus. Mundus is reflected in the modern-day French term monde (world), the Italian mondo, the Spanish mundo and the Portuguese mundo, among other "Romance language" ancestors of Latin.

The Roman author Pliny the Elder (Gaius Plinius Secundus), who wrote a large set of volumes on natural history in the first century, used mundus quite a bit in his observations, Hovell said. It is also from Pliny that we get a lot of the terminology used to name planets through the International Astronomical Union, although each culture has its own traditions and monikers.

The tradition of planet naming used by the Romans dates as far back as the Babylonians at least. Babylonia was a complex state in parts of modern-day Iraq and Syria best remembered for its king, Hammurabi, who today is closely associated with a law code created under his reign.

Babylonia persisted from about 1900 through 539 B.C.; the region was then taken over by the Persians (then the Achaemenid Empire). The Persians became the great enemy of the Greeks, but the two empires also shared a lot of intercultural knowledge. This is how the Greeks incorporated some of the gods from Persia, Hovell explained.

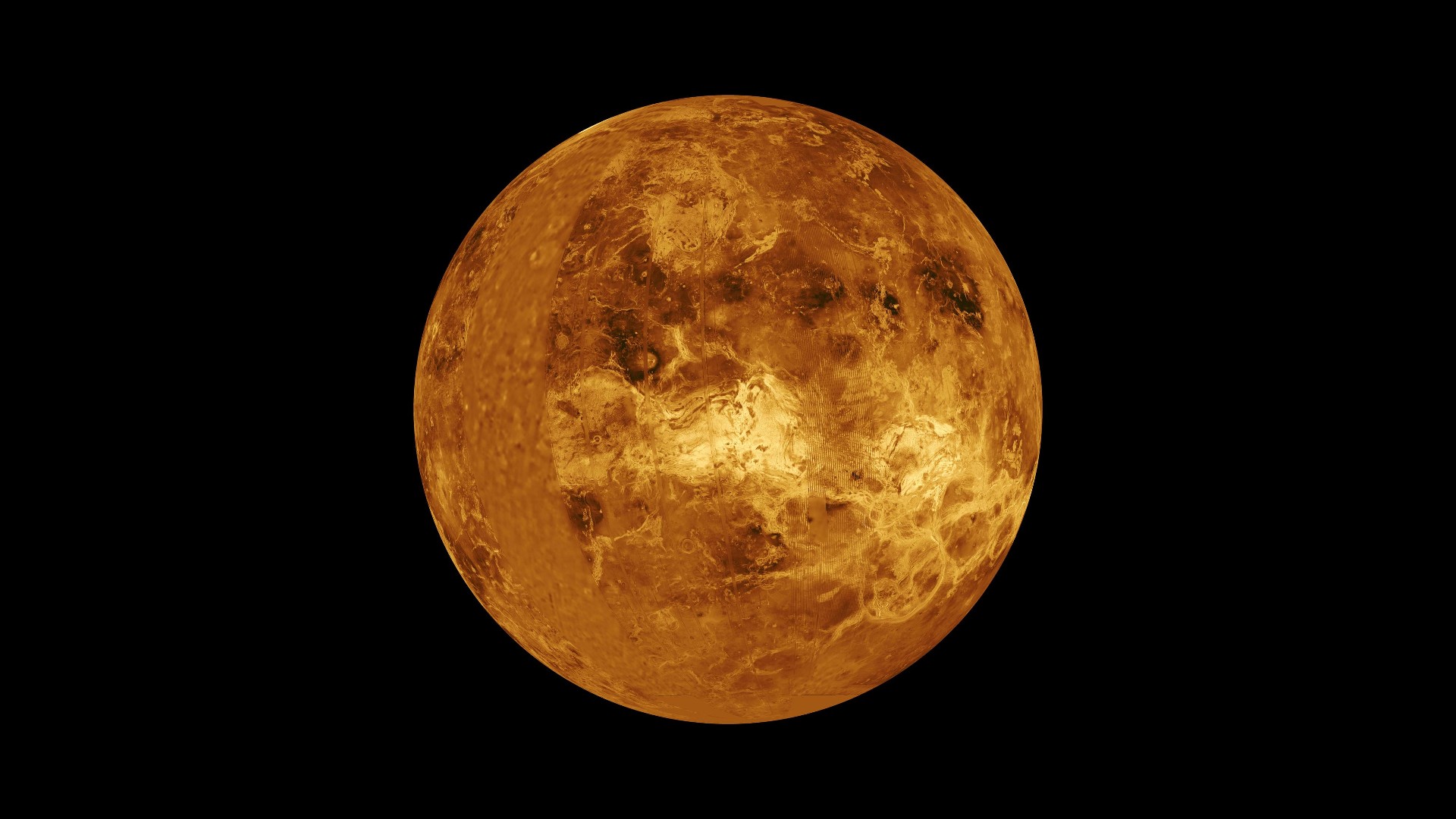

Then when the Romans came to the fore, they integrated traditions from the regions they touched — including Greece — into their own pantheon of gods. This allowed for a goddess of love from Babylonia, Ishtar, to become Aphrodite under the Greeks and Venus under the Romans, for example. (This is a very simplified chronology, however, as Roman gods and goddesses had attributes based on their location, celestial timings and other factors, and the same is likely true of other traditions they integrated, historians say.)

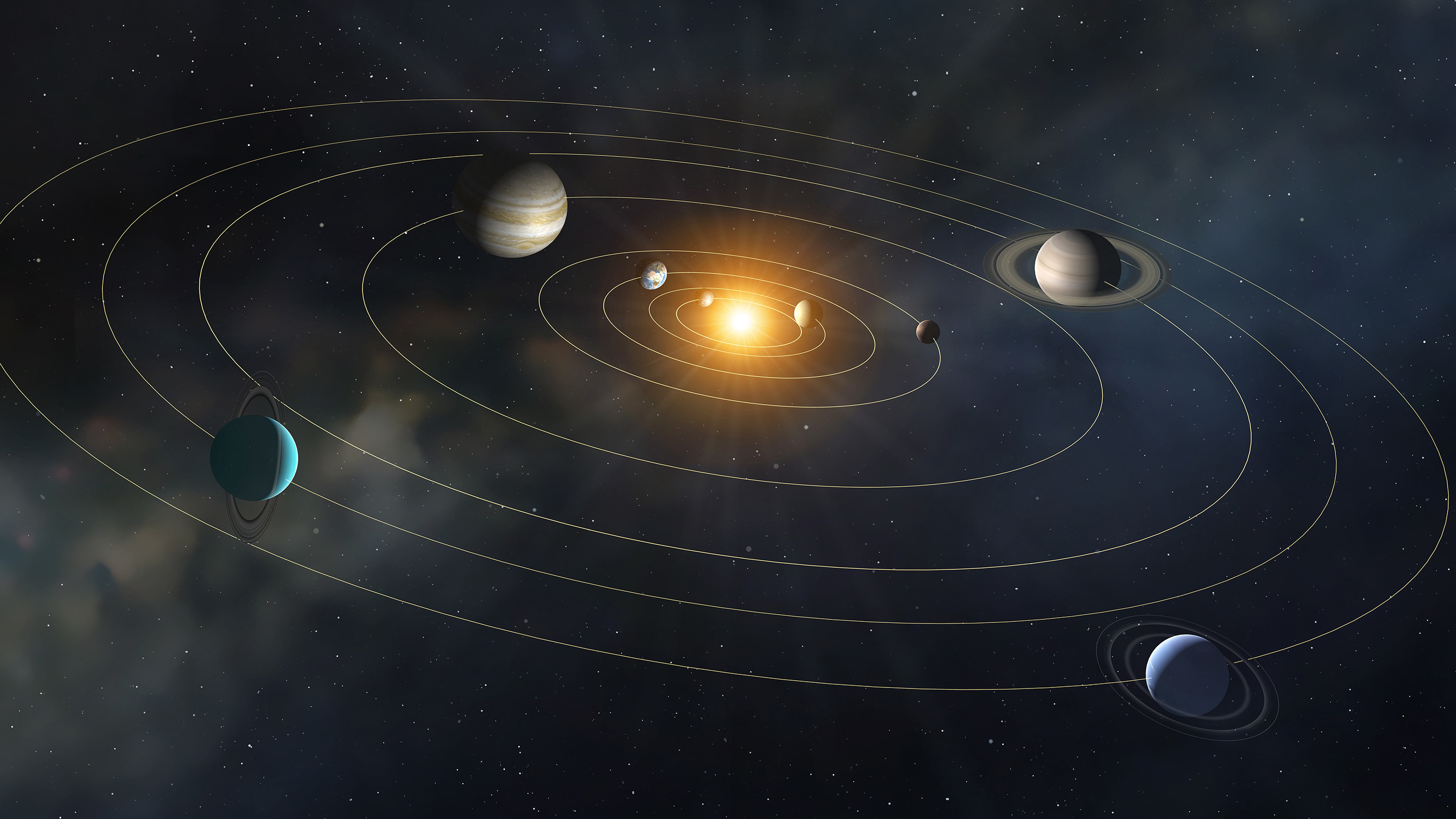

The Greek term for planets means something like "wandering ones" or "wanderer," according to the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum. The Romans gave these planets names based on how they appeared to the naked eye in the sky, centuries before telescopes were available. But these names aren't always universal, either.

Pliny the Elder sometimes called Mercury by another god's name, Apollo, because Apollo was closely associated with the sun, Hovell said. Mercury himself was a messenger of the gods and associated with travelers, among many other connotations.

The planet named after Venus — whose associations include the goddess of love — was sometimes called Lucifer, the "light-bringer" (light is lux in Latin). This was the name the planet might take in the morning, when it rises at dawn. The Romans, Hovell said, understood Venus rises in the morning or the evening, but the planet's name could change depending on the attributes on display.

Mars, Pliny once wrote, is "burning with fire." Pliny thought that Mars was very close to the sun, as he and other Romans of the day were following Ptolemy's geocentric model that put Earth at the center of the universe.

Jupiter's bright appearance was associated with the king of the gods, and Saturn (who came after Jupiter in the geocentric model) is Jupiter's father under Roman mythology, which again borrows from older traditions, Hovell said.

Incidentally, the people who named Uranus, Neptune and Pluto centuries later, in the early telescopic age, tried to carry on this tradition of godly associations to be consistent with how the Romans did it. But even this practice was not universal. For example: Uranus was almost named after George III when its discoverer, German-born British astronomer William Herschel, sought a way to thank his financial backer, according to NASA.

Originally published on Live Science.

Elizabeth Howell was staff reporter at Space.com between 2022 and 2024 and a regular contributor to Live Science and Space.com between 2012 and 2022. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, speaking several times with the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus