Small Earthquakes May Cause Surprisingly Big Tsunamis

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Mysterious small tremors in the most earthquake-prone areas on Earthmay be the cause of surprisingly large tsunamis, researchers say.

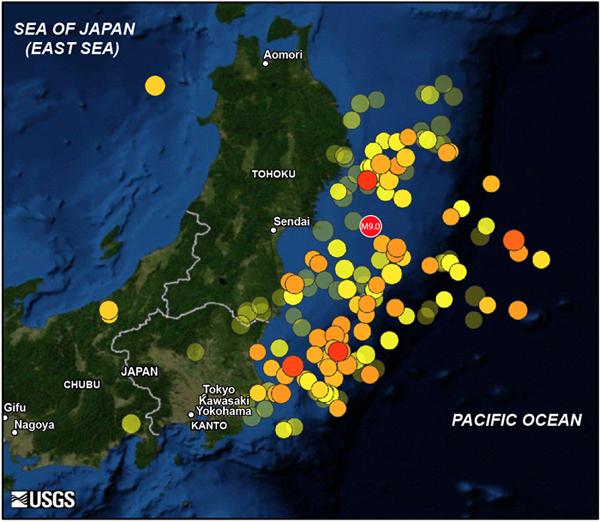

These findings might also shed light on the huge tsunami generated by the disastrous magnitude 9.0 quake that hit Japan in 2011.

Nearly all of the 10 largest recorded earthquakes on Earth happened along subduction zones, where one of the tectonic plates making up the planet's surface is diving beneath another. The shallow regions of these zones are often not seismically active by themselves, but occasionally strange tremors are recorded from these locales that are rich in very-low-frequency seismic waves.

These shallow areas also seem to be home to so-called tsunami earthquakes, which generate tsunamis far stronger than one would expect for the amount of seismic energy they release. The Keicho quake of 1605 that caused disastrous tsunamis in Japan and killed thousands might have been one such earthquake.

To see if there were any links between the very-low-frequency events and tsunami earthquakes seen in the shallows of subduction zones, scientists in Japan used three ocean-bottom seismometers to analyze a swarm of very-low-frequency events in 2009. These occurred in the shallowest parts of the Nankai Trough, a part of a subduction zone near southwestern Japan that is rocked by giant earthquakes every century or so — most recently in 1946, when a magnitude 8.2 event killed an estimated 1,300 people.

The researchers discovered that the very-low-frequency quakes — ranging from magnitudes of 3.8 to 4.9 — can last 30 to 100 seconds. This is unusually long when compared with the 1-to-2 second duration of ordinary earthquakes with comparable magnitudes.

Although these very-low-frequency quakes get their name from seismic waves detected on land, the researchers discovered these events are actually rich in high-frequency waves as well. High-frequency waves tend to weaken with distance as they go through matter, which is why land seismometers did not detect these waves but ocean seismometers closer to the quakes did. The long duration of the quakes and the high-frequency waves now seen from them suggest these events may be caused by fluid seeping into fractures in the rock, making it easier for parts of the earth to slip past each other and generate tsunami earthquakes.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

These findings suggest that authorities should keep a closer eye on the shallow areas of subduction zones. For instance, the huge tsunamis generated by the magnitude 9.0 quake that struck Japan in 2011 might be due in significant part to a slip in the shallow parts of the Japan Trench lying east of the country's main island.

"It is very important for us to monitor continuously seismic activities close to the trench," researcher Hiroko Sugioka, a seismologist at the Japan Agency for Marine-Earth Science and Technology at Yokosuka, told OurAmazingPlanet. "It is mitigation against unexpectedly large tsunami disasters."

The scientists detailed their findings online May 6 in the journal Nature Geoscience.

Follow OurAmazingPlanet for the latest in Earth science and exploration news on Twitter @OAPlanet and on Facebook.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus