Satellite Spies California Fire's Scars

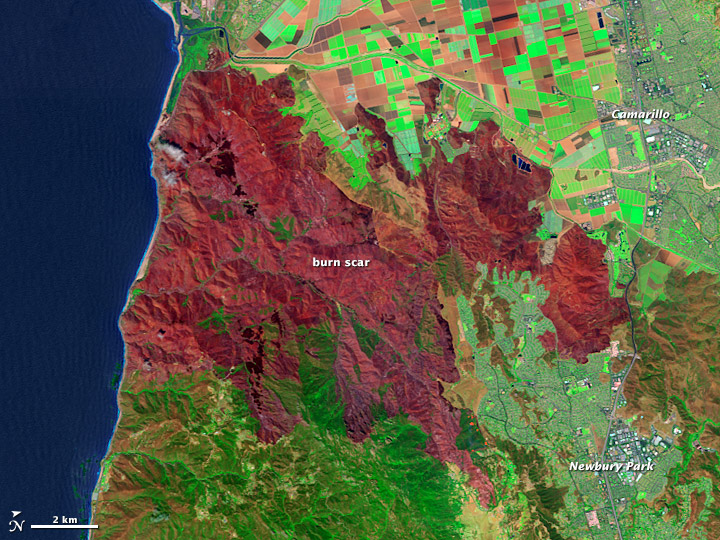

A fire that swept through 240,000 acres in Southern California over the past week is visible from space in a new image from a NASA satellite.

The Springs Fire rushed through scrubland in Ventura County, Calif., starting on May 2, triggering hundreds of evacuations and threatening the towns of Camarillo and Newbury Park. Strong winds and low humidity helped fan the flames.

Firefighters brought the blaze under control within a week, and only 16 buildings were damaged, according to NASA's Earth Observatory. But after a fire, danger still remains — particularly the threat of landslides in areas where vegetation has burned off.

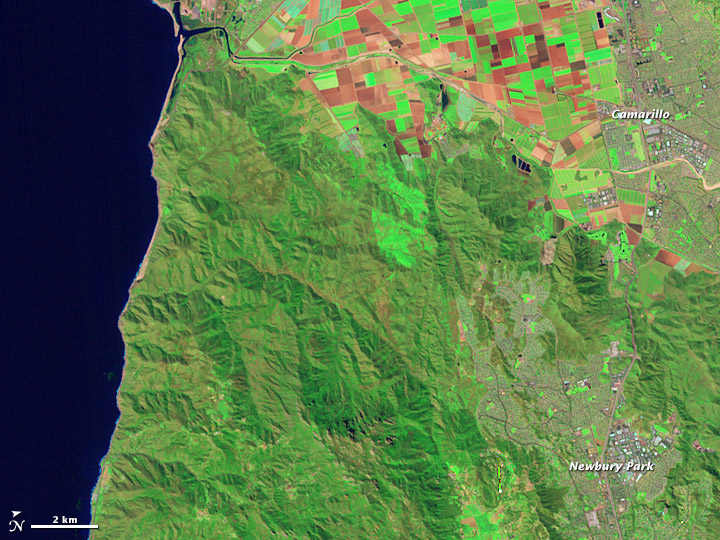

That's where satellite imagery comes in. The Landsat Data Continuity Mission, NASA's eighth Landsat satellite, launched this February and passed over the Springs Fire burn area on May 4. Burned areas appear in red, with the darkest maroons representing the worst-affected spots. Unburned vegetation is green and plowed farmland is brown. An earlier image from 2010 shows the landscape before the Springs Fire blazed through.

Burned Area Emergency Response (BAER) teams use this imagery to pinpoint problem areas for erosion and water run-off.

"Having a new Landsat satellite on orbit is critically important," Randy McKinley, a U.S. Geological Survey geographer who makes burn maps, told NASA's Earth Observatory. "We have to deliver our maps to the BAER teams within a week for them to be most useful, and our odds of getting timely high-quality cloud and smoke-free image acquisitions just went up dramatically."

The new satellite passes over most wildfire areas at least every eight days, McKinley said. That's twice as often as earlier satellites. The satellite also collects about 400 images per day compared to 250 from earlier versions.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Follow Stephanie Pappas on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.com.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.