How We Hear: Mystery Unraveled

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Scientists have figured out how trap doors and tunnels in your ears translate sound and movement into hearing and balance. The finding could one day help reverse genetic deafness and restore hearing lost by construction workers and concert-goers.

A protein from a gene called TRPA1 turns mechanical sound into electrical information for the brain, the study found.

"This could allow for the development of new gene therapies for deafness and balance disorders in the next five to ten years," said neuroscientist Jeffrey Holt of the University of Virginia, who led the research.

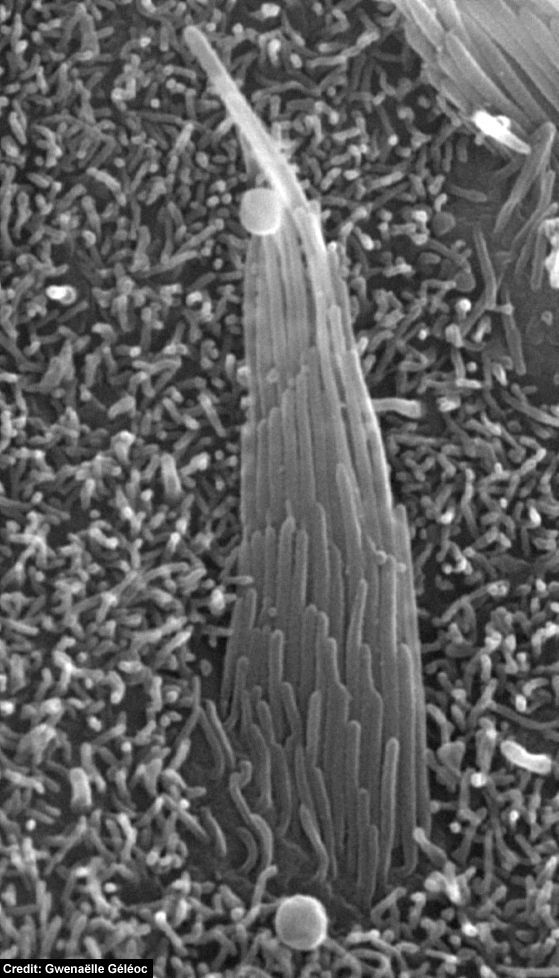

Here's how hearing works, Holt's team found: Inside the cell membrane of the hairs of the inner ear the protein forms a channel like a donut.

"When sound strikes the protein the hole pops open like a trap door, an electrical signal is generated which is relayed to the brain for interpretation," Holt explained.

Different structures are responsible for hearing and balance in the ear, but they both depend on the tiny hairs where the proteins reside to interpret stimulus. According to Holt the inner ear is a good candidate for gene therapy since it is isolated -- scientists would not have to introduce changes to the entire body.

The protein has both the donut structure and a spring portion that enables the hair cells to be "sensitive to movement as small as the diameter of a gold atom," Holt told LiveScience.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Cochlear amplification, the process that allows the ear to be sensitive to soft tones and specific frequencies, might also result from the TRPA1 protein. The amplification could result from the channels of the protein opening and closing in unison. It's like a child on a swing set, Holt said. When a child pumps her legs alone she go to a certain height, but when she pumps in concert with someone pushing her, she can go much higher.

Using mouse embryos as models, researchers were able to isolate the stage of development when the inner ear hairs were formed. That led to the isolation of the TRPA1 protein.

The discovery was detailed in the Oct. 13 online edition of the journal Nature.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus