Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Like a pair of Velcro stripper pants, gecko tails come off easy. The lizards have pre-formed score lines in their tail that allow them to quickly rip off their tails when a predator has grabbed it, according to a new study.

The gecko tails, which were described Wednesday (Dec. 19) in the journal PLoS One, essentially stick to the body of the animals with adhesive forces.

"The tail contains 'score lines' at distinct horizontal fracture planes where the tail may be released as a response to predation," the authors wrote in the article. "These scores penetrate all the way through the tissue where the structural integrity is maintained by adhesion forces."

While scientists have long known that geckos and other amphibians shed their tails to evade predators (and then regenerate them later), exactly how has been steeped in mystery. One possibility was that the lizards had special fast-acting chemicals that essentially broke down connective tissue that held the tail on. But it wasn't clear how chemicals could do that so quickly. [The 10 Weirdest Animal Discoveries of 2012]

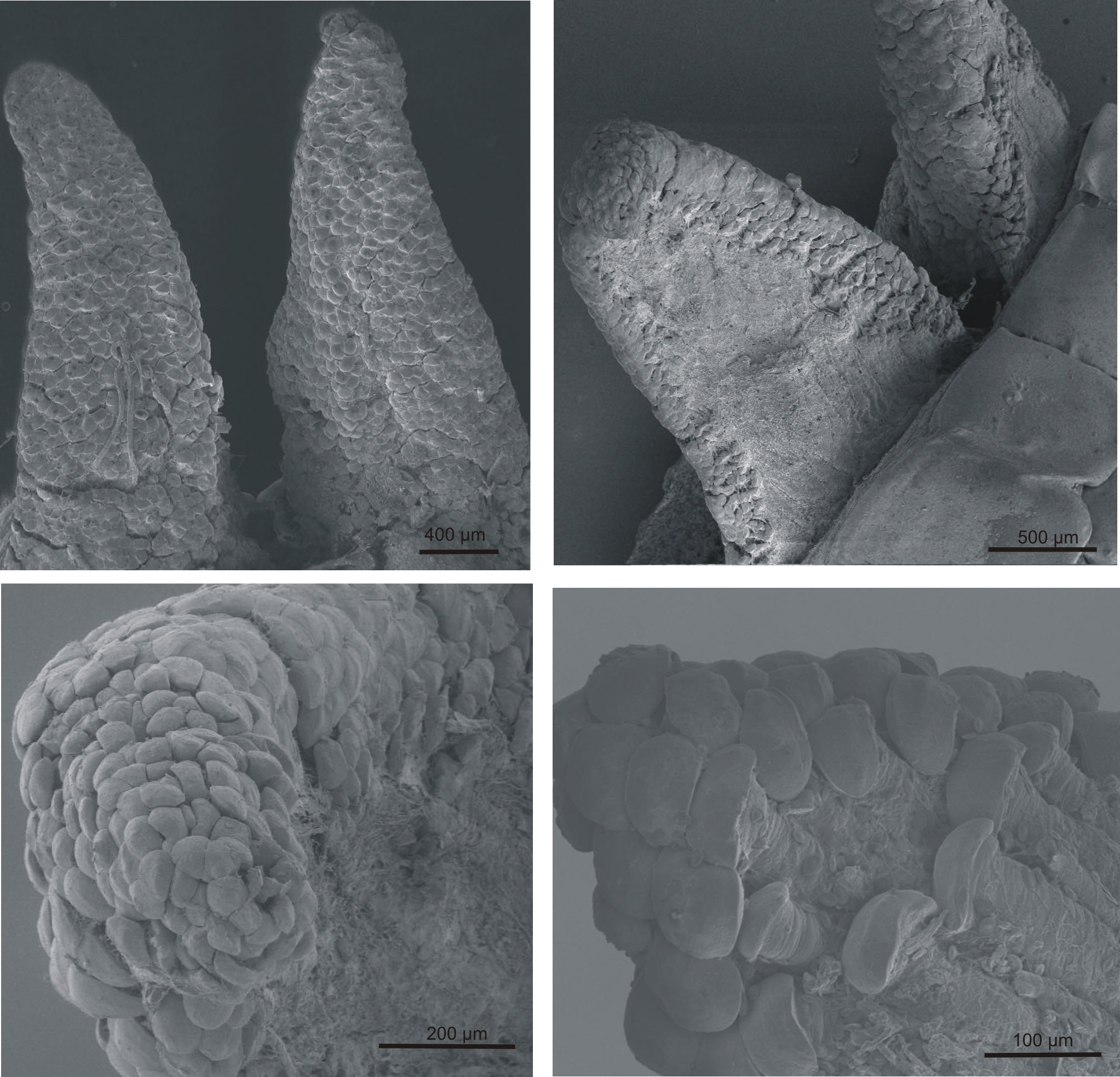

They found the gecko tail had zigzag lines that separated segments of the tail, forming a "precut" line. When the geckos shed their tail, they left behind a pointy, crown-shaped stump. At the stump, the team was able to see bizarre, mushroom-shaped structures. Those structures, the team hypothesizes, form to reduce the adhesive, or sticky, forces and allow the gecko tail to rip off.

The team also conducted a chemical analysis and found the lizards don't use enzymes to cut off their tails.

Instead, the gecko tail probably sticks on using adhesive forces, or the stickiness that occurs between two unlike molecules. That chemical "glue" would allow the lizards to quickly shed their tail without causing permanent damage. Because geckos can regenerate their tails, it's a good strategy to evade a predator. Geckos already use mysterious adhesives for their sticky feet, so it's not all that surprising that sticky forces would play a role in other parts of their body, the authors wrote.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"The segmentation permits the release in an orchestrated manner, a design that facilitates the lizard's ability to shed its tail easy and quickly without employing a slow protease-based degradation of connective tissue," the researchers wrote.

Follow LiveScience on Twitter @livescience. We're also on Facebook & Google+.

Tia is the editor-in-chief (premium) and was formerly managing editor and senior writer for Live Science. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Wired.com, Science News and other outlets. She holds a master's degree in bioengineering from the University of Washington, a graduate certificate in science writing from UC Santa Cruz and a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin. Tia was part of a team at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that published the Empty Cradles series on preterm births, which won multiple awards, including the 2012 Casey Medal for Meritorious Journalism.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus