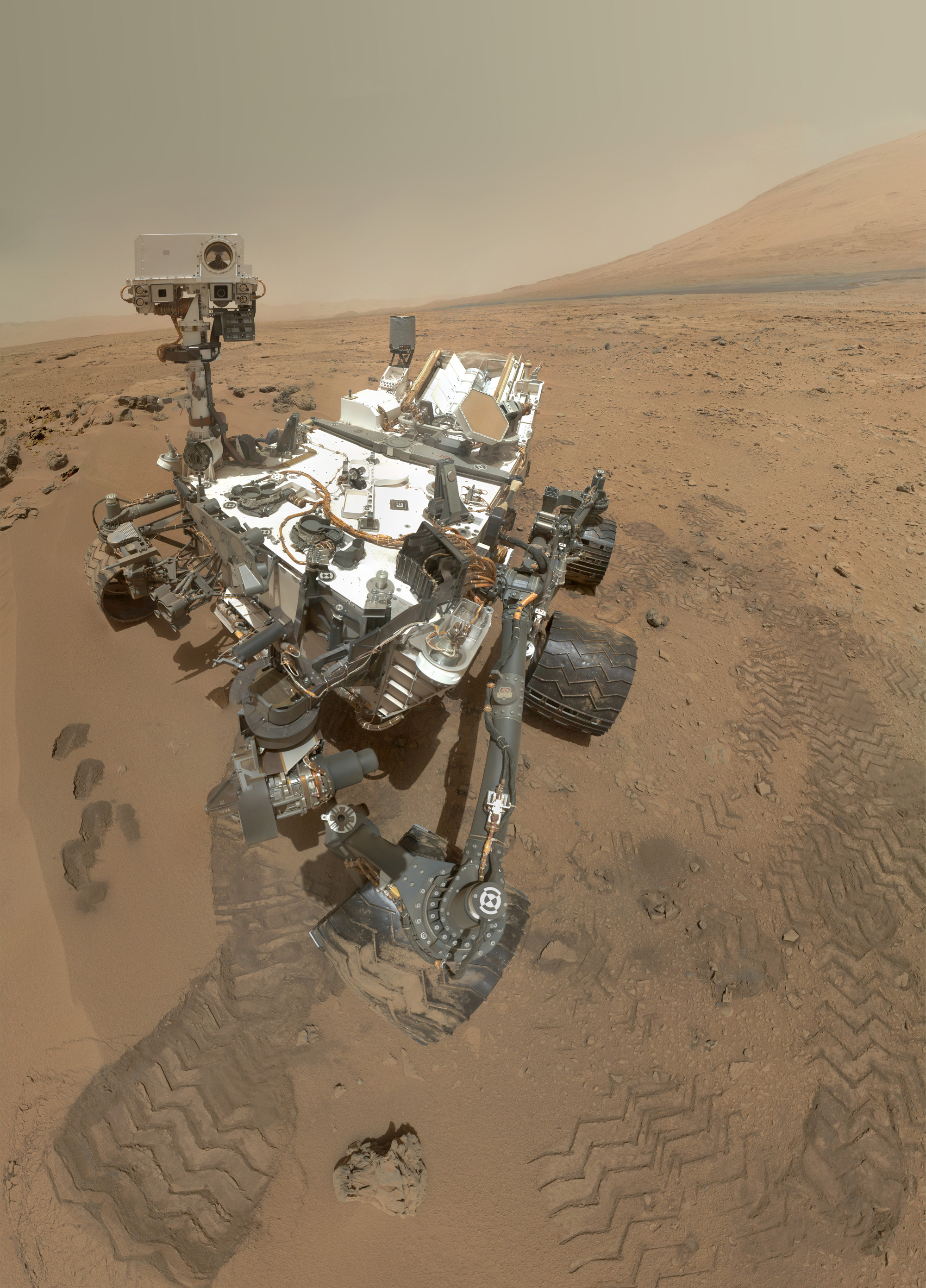

Radiation levels at the Martian surface appear to be roughly similar to those experienced by astronauts in low-Earth orbit, NASA's Mars rover Curiosity has found.

The rover's initial radiation measurements — the first ever taken on the surface of another planet — may buoy the hopes of human explorers who may one day put boots on Mars, for they add more support to the notion that astronauts can indeed function on the Red Planet for limited stretches of time.

"Absolutely, astronauts can live in this environment," Don Hassler, of the Southwest Research Institute in Boulder, Colo., told reporters during a news conference today (Nov. 15).

Hassler is principal investigator of Curiosity's Radiation Assessment Detector instrument, or RAD. RAD aims to characterize the Martian radiation environment, both to help scientists assess the planet's past and current potential to host life and to aid future manned exploration of the Red Planet. [Video: Curiosity Takes First Cosmic Ray Sample on Surface]

Since Curiosity landed on Mars in August, RAD has measured radiation levels broadly comparable to those experienced by crewmembers of the International Space Station, Hassler said. Radiation at the Martian surface is about half as high as the levels Curiosity experienced during its nine-month cruise through deep space, he added.

The findings demonstrate that Mars' atmosphere, though just 1 percent as thick as that of Earth, does provide a significant amount of shielding from dangerous, fast-moving cosmic particles. (Mars lacks a magnetic field, which gives our planet another layer of protection.)

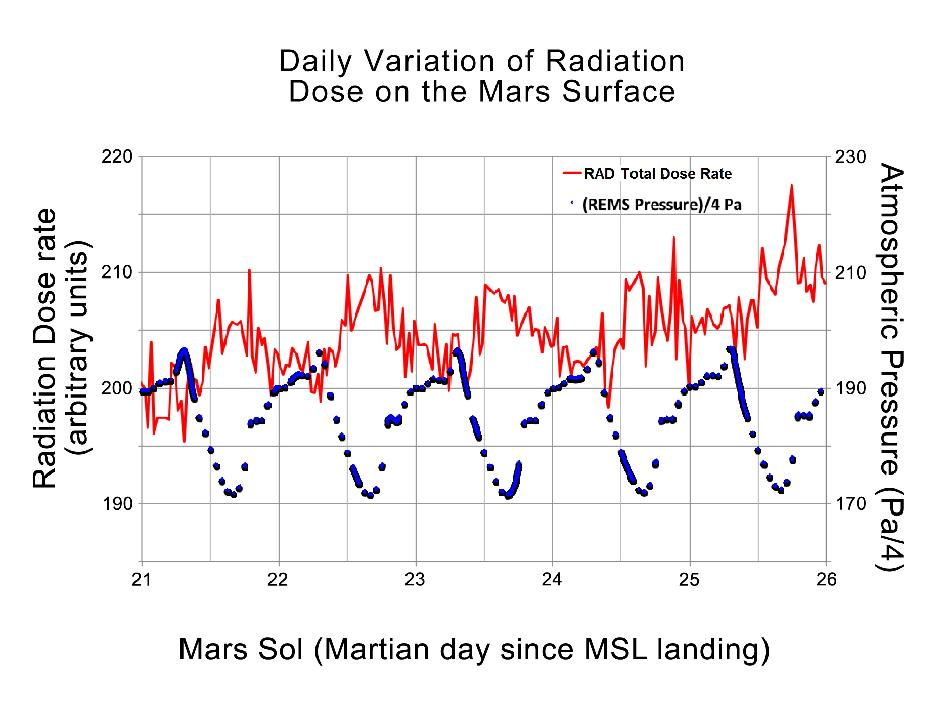

The $2.5 billion Curiosity rover is getting a bead on the nature of this shielding. RAD has observed that radiation levels rise and fall by 3 to 5 percent over the course of each day, coincident with the daily thickening and thinning of the Martian atmosphere, researchers said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Hassler stressed that RAD's findings are preliminary, as Curiosity is just three months into a planned two-year prime mission. He and his team have not yet put hard numbers on the Martian radiation levels, though they plan to do so soon.

"We're working on that, and we're hoping to release that at the AGU meeting in December," Hassler said, referring to the American Geophysical Union's huge conference in San Francisco, which runs from Dec. 3-7. "Basically, there's calibrations and characterizations that we're finalizing to get those numbers precise."

The real issue for human exploration, he said, is determining how much of a radation dose any future astronauts would accumulate throughout an entire Mars mission — during the cruise to the Red Planet, the time on the surface and the journey home.

"Over time, we're going to get those numbers," Hassler said.

One key to understanding the big picture will be documenting the effects of big solar storms, which can blast huge clouds of charged particles into space. Curiosity flew through one such cloud on its way to Mars but has yet to experience one on the surface, Hassler said.

RAD is just one of Curiosity's 10 different science instruments, which it's using to determine if the Red Planet could ever have supported microbial life. During today's press conference, researchers also detailed some initial findings about the Martian atmosphere, including interesting wind patterns and details about daily changes in atmospheric density.

"If we can find out more about the weather and climate on present-day Mars, then that really helps us to improve our understanding of Mars' atmospheric processes," said Claire Newman of Ashima Research in Pasadena, Calif., a collaborator for Curiosity's Rover Environmental Monitoring Station instrument. "That gives us much more confidence when we try to predict things like what Mars may have looked like in the past."

This story was provided by SPACE.com, a sister site to Live Science. Follow SPACE.com senior writer Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwallor SPACE.com @Spacedotcom. We're also on Facebook and Google+.