Satellite Radar Could Predict Deadliest Eruptions

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

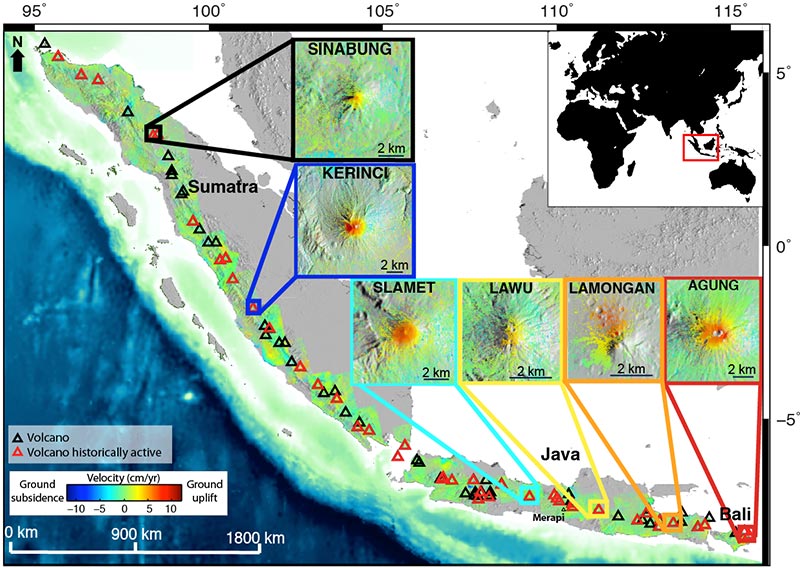

The world's deadliest and largest volcanic eruptions happen in Indonesia. Future eruptions in this jungle-filled region could be better predicted by using satellite radar to detect swelling magma near the summit of those volcanoes, a new study suggests.

To search for evidence of imminent eruptions, scientists monitored surface changes at 79 volcanoes with technology called Synthetic Aperture Radar Interferometry (InSAR). The data were gathered between 2006 and 2009 by the Japanese Space Exploration Agency's ALOS satellite.

The researchers found that six volcanoes in Indonesia "inflated" during the study period — and three of these later erupted. One was the thought to be dormant: Mount Sinabung, which inflated 3 inches (8 centimeters) in 2007 and 2008 before erupting in 2010. More than 17,500 people were evacuated.

"If we could have had this data in real-time, we could have had an idea that this was not a dormant volcano," said study author Estelle Chaussard, a doctoral student at the University of Miami in Coral Gables, Fla.

Watching magma move

Remote sensing by satellite could be a valuable tool for predicting eruptions in Indonesia, including its largest island Sumatra, Chaussard told OurAmazingPlanet.

The nation is home to 13 percent of the world's most active and lethal volcanoes, but threats such as tigers and thick jungle vegetation make ground-based GPS monitoring nearly impossible.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"I'm hopeful in the future we could use InSAR are a forecast tool," Chaussard said. "With this type of survey, we are able to see the big picture. You can detect the behavior of volcanoes with time, even if you are in jungle conditions, where you don't have ground monitoring."

When molten rock travels though underground passages beneath a volcano, the ground above it changes, with some areas inflating as magma moves upward and others deflating as a magma chamber empties.

Indonesian volcanoes are covered by thick vegetation, and in general, radar bands can't penetrate such plant life. The ALOS used a special radar band to collect its data. While that satellite is now defunct, a replacement, ALOS-2, is planned for launch in 2013.

The study is the first time several volcanoes were monitored simultaneously using this technology. Researchers have detected pre-eruption deformation by satellite before, for instance, on individual volcanoes in Alaska and Hawaii.

Eyes in the sky, hazards on the ground

Geophysicist David Sandwell, who was not involved in the study, told OurAmazingPlanet that InSAR technology could also be useful for monitoring volcanoes in other remote areas such as in the Aleutian Islands, where eruptions interfere with overseas flights. "No one can get there because it's so far away," said Sandwell, a professor at Scripps Institute of Oceanography in San Diego, Calif.

InSAR combines two or more radar images of a ground location in a way that allows scientists to make very precise measurements of changes between images.

However, further research is needed to see whether the study's results may apply beyond Indonesia, Chaussard said. Indonesian volcanoes have very shallow magma reservoirs — located 0.5 to 2 miles (1 to 3 kilometers) directly below the summit — which make measuring summit inflation a good method of predicting eruptions.

Not all volcanoes in the study showed inflation before blowing their tops, the researchers noted. Mount Merapi spewed hot gas and ash in 2007 and 2008, with no previous surface changes. Merapi may have an open conduit of magma, rather than a constricted magma chamber, the researchers said.

Reach Becky Oskin atboskin@techmedianetwork.com. Follow her on Twitter @beckyoskin. Follow OurAmazingPlanet on Twitter @OAPlanet. We're also on Facebook and Google+.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus