Watch 2 megamouth sharks caught on video for the 1st time ever

This rare video, showing two megamouth sharks swimming off the coast of San Diego, is scientists' 'only knowledge' of the sharks' social lives.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

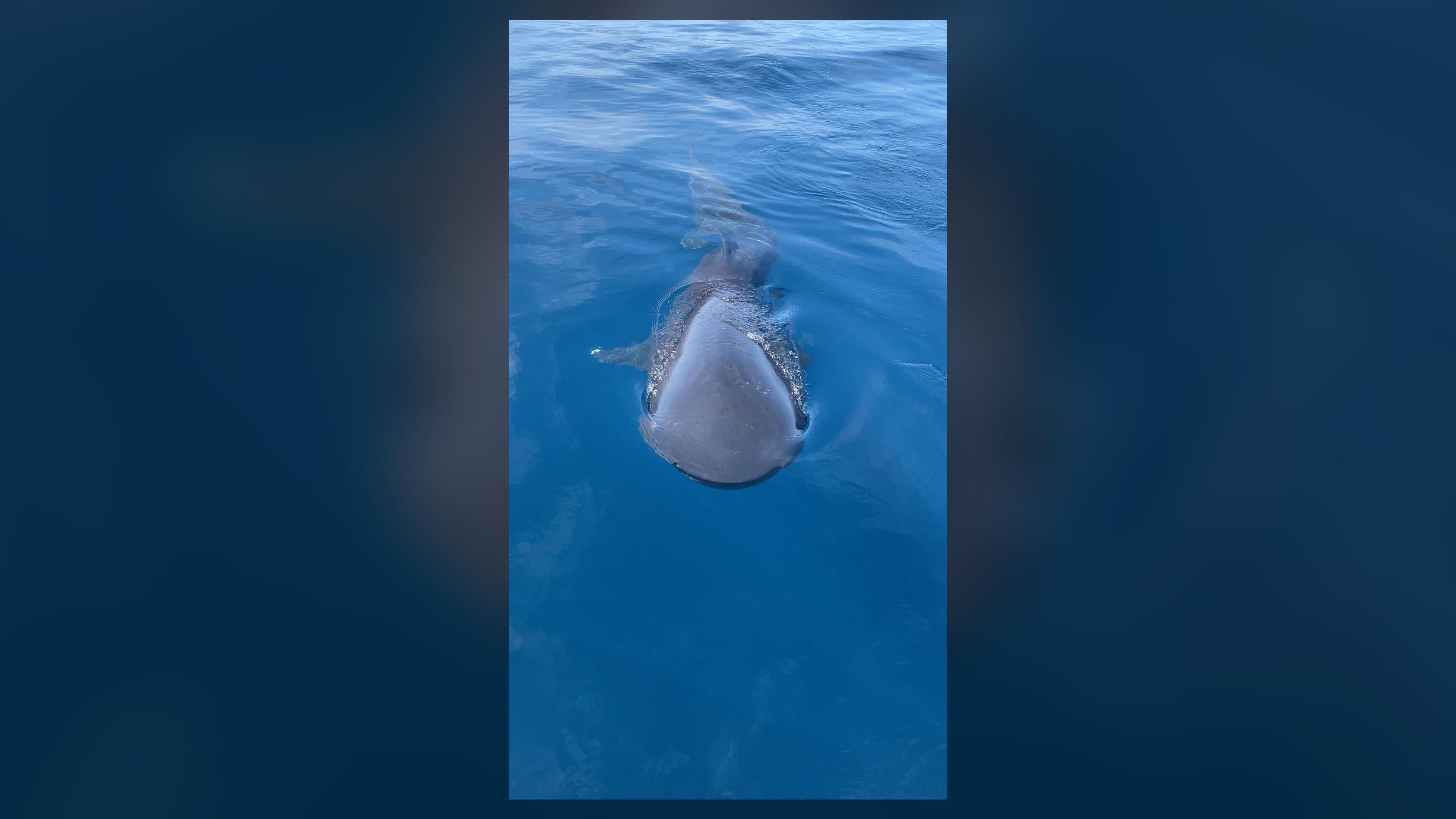

Stunning new footage shows a pair of extremely elusive megamouth sharks (Megachasma pelagios) swimming together off the coast of San Diego.

The video, captured by fishers in early September 2022, may show the deep-dwelling beasts in a courtship ritual and is one of just a handful of sightings of the creatures alive. In the 50 years since the species was discovered, there have been just 273 sightings, most involving sharks caught in fishing gear. Only five megamouth sharks have been spotted swimming freely in the wild. Never before had two been seen swimming together.

Now, a new study analyzing the footage suggests that the two sharks were engaging in courtship or mating behaviors.

"The curiosity of these fishermen benefited the field as a whole," study lead author Zachary Skelton, a graduate student at the University of California, San Diego, told Live Science. "The 10 minutes the fishermen had with the sharks contains the only knowledge we have on megamouth shark sociality."

The elusive megamouth shark can grow to be 18 feet (5.5 meters) in length and weigh up to 2,679 pounds (1,215 kilograms). These bulbous-headed creatures are filter feeders that sift food from the water captured in their enormous mouths. Yet, despite their size and distinctive features, megamouth sharks evaded detection until 1976.

Related: The biggest sharks in the world

"It's pretty darn rare to see one, let alone two at a time swimming at the surface during the day," Christopher G. Lowe, director of the Shark Lab at California State University Long Beach, who was not involved in the study, told Live Science in an email. To better understand megamouth shark behavior, Skelton and colleagues analyzed the footage in light of whatever they could find in the literature on the social behaviors of other filter-feeder sharks, such as basking sharks (Cetorhinus maximus) and whale sharks (Rhincodon typus). "Because the encounter was so brief, we had to heavily rely on other studies and species to try and make sense of why the sharks were at the surface, why they were together, and why at that specific place," Skelton said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Visible male sex organs known as claspers suggested the smaller of the two sharks was male. And although the team could not confirm the sex of the other shark, they determined that it was probably female, based on a lack of obvious claspers and a series of scars on its back similar to the mating scars found on female sharks from other species.

Given that the male was closely following the putative female shark and that neither shark was seen attempting to feed, the researchers concluded that the footage likely reflects a courtship display. The results were published March 13 in the journal Environmental Biology of Fishes.

"This anecdotal observation has all the hallmarks of precopulatory mating behavior," Carl Meyer, an associate researcher at the Shark Research Lab at the Hawaii Institute of Marine Biology who was not involved in the study, told Live Science in an email. "We still know comparatively little about the biology and ecology of megamouth sharks so this observation is an interesting addition to our understanding of this species."

Neil Hammerschlag, director of the Shark Research & Conservation Program at the University of Miami, who was not involved in the study, was similarly impressed. "The paper does a good job of speculating what could be occurring," he told Live Science in an email. "The social behavior of [megamouth] sharks is still a bit of a black box to scientists, and observations like these are exciting, generating a bunch of questions and theories that can be further studied."

Joshua A. Krisch is a freelance science writer. He is particularly interested in biology and biomedical sciences, but he has covered technology, environmental issues, space, mathematics, and health policy, and he is interested in anything that could plausibly be defined as science. Joshua studied biology at Yeshiva University, and later completed graduate work in health sciences at Cornell University and science journalism at New York University.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus