Behind a Visionary: The Science of Steve Jobs

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

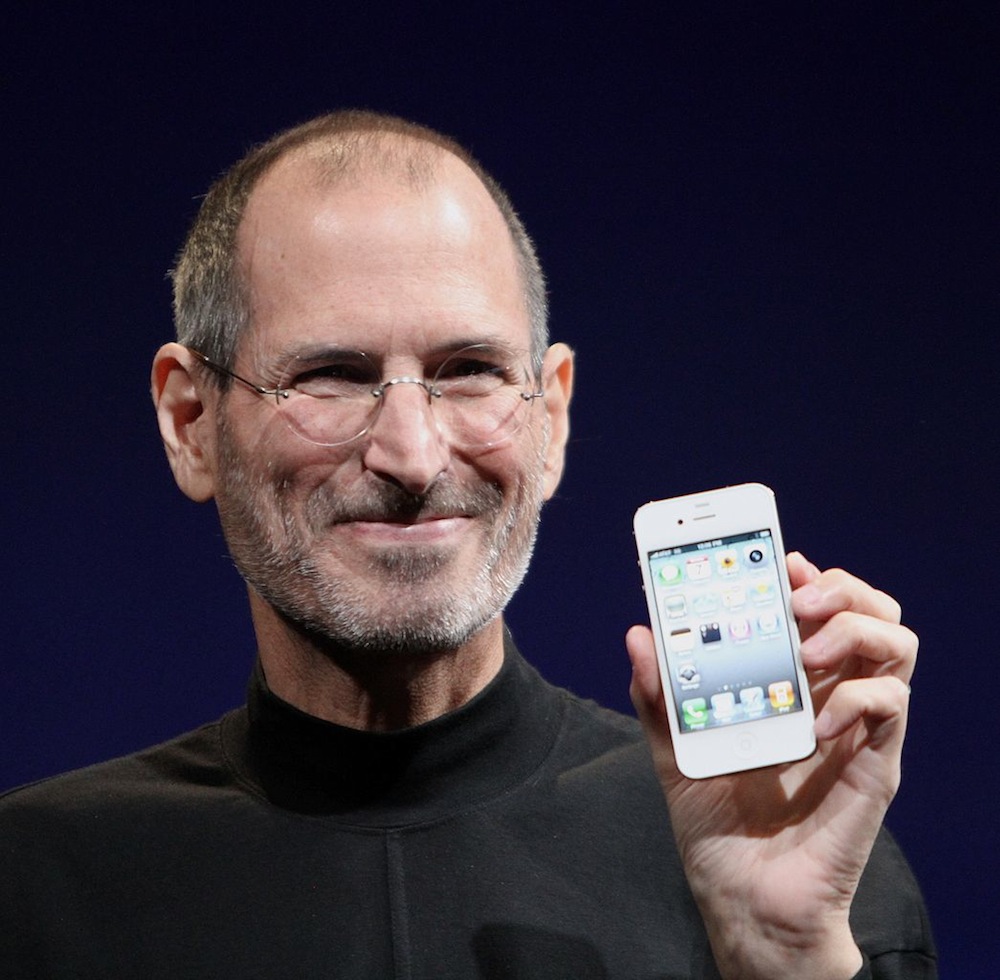

The death of Apple's Steve Jobs on Wednesday (Oct. 5) triggered an outpouring of mourning and celebration. As newspaper obits remembered Jobs as a "visionary" and the "Henry Ford of the computer industry," fans converged on Apple stores across the country to leave notes, bouquets and actual apples.

It's hard to imagine this sort of grief for most other CEOs — would the loss of the head of General Electric or Exxon Mobile spur 10,000 tweets per second? — but Jobs had a combination of smarts, entrepreneurship and salesmanship that linked him closely with Apple and its products. Exactly how a visionary like Jobs develops, however, is still something of a mystery. Social scientists say that talent like Jobs' is neither inborn nor learned, but rather a combination of the two. And while intelligence is key, creativity and charisma matter, too.

"With somebody like Steve Jobs, you're talking about a constellation of personality and intellectual ability factors, and then the role of the environment that he selected for himself can't be underestimated," Michigan State University psychology Zach Hambrick told LiveScience. [19 Greatest Modern Thinkers]

"It's a dynamic process," Hambrick said. "He surrounds himself with really bright people who further elevate his thinking and his expertise and knowledge."

Brainy abilities

The genesis of extraordinary talent is a long-running debate in psychology, Hambrick said. One view holds that experts are born with innate talents that rocket them to the top. Other psychologists have argued that practice and experience overshadow inborn abilities.

The answer is likely somewhere in between. The importance of practice is "undeniable," Hambrick said. "Exceptional levels of performance are almost never reached without at least 10 years of practice and preparation."

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

But even among the dedicated, innate intelligence seems to matter. A 2007 study published in the journal Psychological Science found that even among the smartest people, small differences in intelligence matter for achievement. In that study, Vanderbilt psychologist David Lubinski and his colleagues compared long-term success among people who scored in the top percentile of the SAT math test at age 13. They found that 13-year-olds who scored in the 99.9 percentile of the test were 18 times more likely to get a doctorate in math or science than those who scored "only" in the 99.1 percentile.

Likewise, Hambrick and his colleagues have found that even among people who diligently practice, innate intelligence makes a difference in how well they'll perform. The research, to be published in the journal Current Directions in Psychological Science, reveals that even the most dedicated musicians are better at playing new music on the spot when they score high in working memory capacity.

Working memory is like the brain's desktop, Hambrick said. Closely related to general intelligence, working memory is the brainpower a person can dedicate to consciously processing information. For a musician sight-reading music, working memory allows the person to play one measure while looking ahead to the next notes on the page.

In fact, no matter how much the person practices, Hambrick and his colleagues found, working memory capacity explains 25 percent of the differences in sight-reading ability. Because intelligence and working memory are strongly controlled by genetics, the takeaway message is that brains matter. [10 Things You Didn't Know About the Brain]

"Basic abilities and capacities might limit the upper level of performance that a person can achieve," Hambrick said. "And this is above and beyond the large contributions to performance of practice."

Creativity and personality

Intelligence and working memory may even be connected to another of Jobs' much-lauded traits: creativity. People who have strong working memories also tend to be creative, Hambrick said, though it's not known whether one causes the other. It's possible that working memory influences creativity by giving people more mental "desktop space" to hold ideas and make new connections, he said.

But intelligence and working memory aren't the whole story.

"We all probably know people who are smart, who have a high level of what we call fluid intelligence, the ability to solve novel problems, to think and reason analytically," Hambrick said. "And yet, they're not creative."

That's where personality comes in. By many accounts, Jobs was a demanding person. His colleague Jef Raskin once said he would have made "an excellent king of France." Jobs controlled his image (and Apple's) strictly, and journalists who covered the company often described its CEO as "prickly."

But Jobs was also an outside-the-box type who drew inspiration from Zen Buddhism, experimented with psychedelic drugs in his youth and dropped out of college to visit an ashram in India. Jobs once said of Microsoft founder and competitor Bill Gates, "I wish him the best, I really do. I just think he and Microsoft are a bit narrow. He'd be a broader guy if he dropped acid once or gone off to an ashram when he was younger."

Jobs may have had a point. A recent study found that even one dose of hallucinogenic mushrooms can permanently alter personality, making people more open to new experiences. An "open" personality is associated with creativity, said study researcher Katherine MacLean, a postdoctoral researcher at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine.

That's not to say that Jobs' drug experimentation led him to greatness: "A lot of people around his age went to India, got into meditation and dropped acid," MacLean told LiveScience. "But they didn't become him."

Jobs was almost certainly an open, creative person before he experimented with psychedelics, MacLean said. People who sign up for her research group's studies on psilocybin, the hallucinogen in mushrooms, tend to be more open than the general population already. Young Jobs was likely the same way. [Trippy Tales: The History of 8 Hallucinogens]

"I think he's a classic example of someone who was very high in these things to begin with," MacLean said.

Ego of a visionary

One more factor played into Jobs' success: self-promotion and a strong personality.

"He's a tough, prickly interview," CNN blogger Philip Elmer-Dewitt told U.K. newspaper The Times in 2009. "And he's always selling. Hard."

Jobs' talent at persuasion was so renowned that it got its own name: The "reality distortion field." Apple Vice President Guy "Bud" Tribble coined the term in 1981 to describe how Jobs could convince anyone of anything.

Jobs wasn't afraid to talk up his products. "Today, Apple is going to reinvent the phone," Jobs told an audience at the 2007 rollout of the iPhone. Likewise, the iPad would be "magical and revolutionary," he told reporters at a press conference in 2010.

"Jobs was successful at making himself the brand at Apple," said Darren Treadway, a professor of organization and human resources at the University at Buffalo. "It's almost as if individuals love Jobs because his products let them be more unique and important."

Jobs was savvy about his "celebrity CEO" status, Treadway told LiveScience, using his political skills to control his message and cement Apple's reputation for innovation.

He also backed up his charismatic presentations with strong products, said Michelle Bligh, a professor of organizational behavior at Claremont Graduate University. But charisma has a dark side, too, Bligh told LiveScience. Jobs, with his reported habit of parking in handicap-designated spots (before his illness) and tyrannical tendencies at work, was no exception, Bligh said.

"As long as [charismatic leaders] still have the allure of being successful and famous, people are willing to overlook a lot of flaws," she said. People become even more willing to turn a blind eye after a leader's death, she added. [Read: 10 Most Memorable Steve Jobs CEO Moments]

Strangely, part of Jobs' charisma may not have come from him, but from his situation. He returned to Apple during a time when the company was in disarray and responded with a charismatic communication style: dominant, dramatic and decisive. Those attributes might not have played well in a more stable company, Bligh said. Similarly, she said, President George W. Bush was viewed as more charismatic right after the 9/11 terrorist attacks, even though the only thing that had changed was the situation, not the man.

Jobs also had a knack for appealing to the tech demographic that adored his products.

"In another context, he wouldn't necessarily be perceived as charismatic as he was to the nerdy, we-can-change-the-world Silicon Valley set," Bligh said. "If you're in that environment, he looks like the nerdy messiah that is going to help us turn this company around and change the world — and really did."

You can follow LiveScience senior writer Stephanie Pappas on Twitter @sipappas. Follow LiveScience for the latest in science news and discoveries on Twitter @livescience and on Facebook.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus