Life's Extremes: Outgoing vs. Shy

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

In this weekly series, LiveScience examines the psychology and sociology of opposite human behaviors and personality types.

We all know them: The exuberant, outgoing glad-handers who relish a social gathering, and the reserved, shy wallflowers who might not attend the event at all.

On a given day, of course, any one of us might want to throw a spontaneous party or have some quiet alone time. But in terms of overall sociability, most of us fall within a middle range somewhere between gregarious and shy.

Article continues belowA minority of people, however, cannot get enough social interaction, and some outright dread it.

As for how we come to have such varied personalities as adults, science increasingly supports what many of us would suppose: A combination of "nature" (innate biology) and "nurture" (environment and upbringing) shape our modes of behavior. [Read: Personality Predicted By Size of Different Brain Regions]

"It's the old [saying], 'Biology is not destiny,'" said Nancy Snidman, director of research in the Child Development Unit at Children's Hospital Boston. "There's a lot of variability in the system, which also means flexibility."

Born this way

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Long-term studies tracking infants through early adulthood have suggested that we are born with predispositions to respond to the environment in a particular way.

Psychologists refer to this built-in responsivity as "temperament." (The familiar labels of introvert (preferring solitary activity) or extrovert (seeking social excitement) fall under this category.) [Read: Brains of Introverts Reveal Why They Prefer to Be Alone]

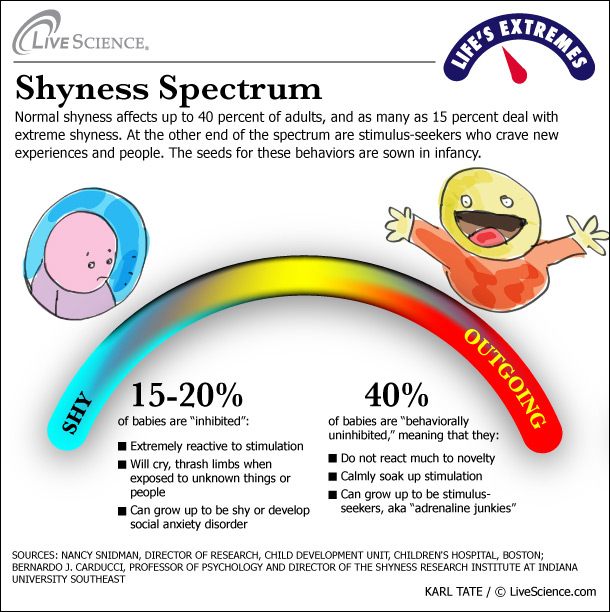

Temperament-wise, Snidman and her colleagues have seen that about 40 percent of babies are "behaviorally uninhibited," meaning they do not react much when shown novel stimuli. "They will sort of sit there and take in novelty in a calm way," said Snidman.

Another 15 to 20 percent of infants are on the opposite, inhibited side of the behavior continuum. When presented with unknown lights, sounds, objects or people, this latter group "is extremely reactive," said Snidman, and these babies will thrash their arms and legs about, cry or show other signs of behavioral arousal. [Read: Personality Set for Life By 1st Grade]

On into adulthood

These unruffled or anxious bassinet portraitures speak to future personalities. Those who calmly soak up stimulation, for instance, are likely to continue to want to do so. "If you're outgoing and relaxed and like new adventures, you're probably going to stay that way," said Snidman.

But stimulation-seeking can go too far. The 5 percent or so of kids who go on to develop attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) tend to come from the behaviorally uninhibited pool. "Some of those kids are understimulated and go looking for risky behavior and stimulation," said Snidman.

It's little surprise then that ADHD in teens and adults has been tied to many adverse life outcomes, such as higher incidences of car crashes and crime. Some studies have found that nearly half of prison inmates have ADHD (often undiagnosed and untreated).

From hesitant to hermitic

As for that overstimulated 15 to 20 percent of infants who as toddlers still hold onto their mothers' legs, a small percentage of them cower on into adolescence, said Snidman.

At least that's the picture in the United States, where sociability is culturally valued over solitude. "There is a lot of pressure in the U.S. not to remain with that [inhibited] temperament," noted Snidman.

But "normal" shyness is quite common, affecting about 40 percent of adults, according to Bernardo J. Carducci, professor of psychology and director of the Shyness Research Institute at Indiana University Southeast. "Shy people will go to parties, bars, art openings, public places — they don't have a problem going, they have a problem performing," Carducci said.

Some of these individuals — perhaps as high as 15 percent of the population — cross the border from typical shyness and social awkwardness into so-called social anxiety disorder. Carducci described sufferers of this malady as "people who can get on a bus, go to work and hold down jobs, but have trouble in social situations and won't go to them."

At the farthest end, people with full-fledged social phobia "have trouble leaving their house," Carducci said, due to persistent feelings of humiliation coupled with extreme shyness. About 2 percent of the U.S. adult population has this severe form, according to the National Institutes of Mental Health. (Another very similar mental illness, called avoidant personality disorder, is also recognized within psychiatry, and affects perhaps 5 percent of adults.) [What Really Scares People: Top 10 Phobias]

Medications, including selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), can help, underlining the biological component of personality.

Neuro-personality

A myriad of biochemicals influence the way we act, including whether we shy away from or run toward stimulating activity.

"Introverts tend to have a more sensitive nervous system, and because they react stronger they withdraw to minimize stimulation," said Carducci. He offered the analogy of a loudspeaker blaring music: "[Introverts] move away from a speaker to reduce noise, and they do that because the internal volume control in their brain is set a little higher. With extraverts, it's set a little lower."

Among the key factors impacting this sensitivity, Carducci said, is the level of monoamine oxidase (MAO) in the brain. This enzyme breaks down neurotransmitters, such as serotonin, which cells use to communicate. "MAO is like a brake system in a car," Carducci said. Extraverts tend to have lower amounts of MAO, thus they are more go-go than introverts.

One part of an introvert's brain that is jazzed up, however, is the amygdala, according to functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) studies. The amygdala plays a role in generating feelings of fear.

Genes, with influences from the environment, determine the form and function of our brains and bodies. But discrete genes for gregariousness or reclusiveness have not turned up, nor are they expected to, as personality and behavior are a complex interplay of what's in us and around us, so to speak.

And while we cannot "will" our hair to be a different color or our frames to grow a few inches taller, we can consciously modify our behaviors to become less attention-craving or clammed up.

"You can practice and get better on a day-to-day basis," said Carducci. "Even if you have an inhibited temperament, it doesn't mean you have to be that way."

Follow LiveScience for the latest in science news and discoveries on Twitter @livescience and on Facebook.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus