Flesh-Eating Bacteria's Rise Tied to Antibiotic Cream

After getting a cut, many Americans will reach for a tube of over-the-counter antibiotic cream to ward off infection. But that widespread habit, a new paper suggests, may be contributing to the rise of one of the most concerning strains of drug-resistant bacteria.

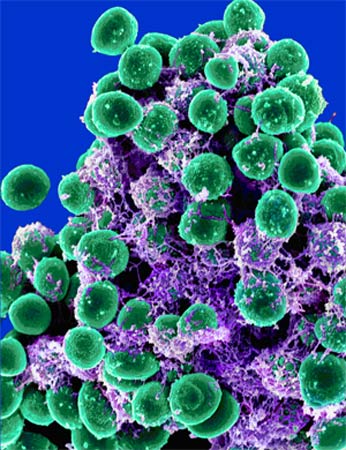

Japanese researchers looked at 261 samples of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), including 21 samples of the USA300 strain, a type of MRSA that has gained attention for its spread, its frequent presence in the community as well as the hospital, and its link to necrotizing fasciitis, also known as flesh-eating disease.

They found that while other MRSA strains were somewhat susceptible to some combination of the antibiotics bacitracin and neomycin — which are typically found in over-the-counter creams — only the USA300 strains were resistant to both. The authors said this may mean that overexposure to those antibiotics is what led to USA300's resistance.

"People should understand that triple antibiotic [ointment] is not almighty, and avoid preventive or excessive use of this ointment," said study author Masahiro Suzuki, a bacteriologist at the Aichi Prefectural Institute of Public Health in Nagoya, Japan.

How the USA300 strain arose

The origin of the USA300 strain has remained unknown, in part because, unlike other MRSA strains, it appears to have evolved outside of hospitals.

"Over the past decade or so, it's really emerged as the leading cause of skin and soft tissue infections in the community," said Dr. Henry Blumberg, a professor of infectious disease at Emory University who has studied USA300 at Grady Memorial Hospital in Atlanta.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

While other antibiotic-resistant bacteria arose in hospitals, where antibiotic use is common, and then spread out into communities, USA300 was first found in community infections, and spread from there.

"Now it's causing hospital infections," he said. "Now the lines are a little more blurry between the community and hospital."

Because USA300 is in the community, a number of groups are particularly susceptible to the strain, including children, gay men, prison inmates, military recruits, tattoo recipients and athletes, the study said.

But Blumberg said, "I think we're beyond that. These groups may have higher risk, but these things spread throughout the population."

Suzuki similarly told MyHealthNewsDaily that "all USA residents have a risk for USA300 infections anytime and anywhere, and should be careful to keep cuts and scrapes clean and covered, avoid contact with other persons' infected skin, wash hands frequently, avoid sharing personal items to minimize risk of infection."

Are antibiotic creams to blame?

While he agreed the bacteria are a threat, Blumberg said he was somewhat skeptical of the authors' hypothesis that over-the-counter ointments are driving the presence of USA300.

"They have a theory that use of topical, over-the-counter creams and antibiotics select this USA300 clone and that's why it's emerged," Blumberg said. "They haven't proved it."

Blumberg said that he is hesitant about the theory because "from my experience, most of the patients we see haven't used topical antibiotics." But, he said, "I think it's an interesting theory. It would be interesting to see if this was widespread in a bigger collection of USA300 isolates."

While USA300 is resistant to a number of drugs, it remains treatable — for now.

"In point of drug resistance, USA300 is not dangerous," Suzuki said, "because most USA300 strains are susceptible to not only [the antibiotic vancomycin] or other anti-MRSA agents but also clindamycin, aminoglycosides or sometimes quinolone. However, I'm afraid that USA300 [will acquire] resistance to other antimicrobial agents in the future, because USA300 now caused not only community-associated but healthcare-associated infections."

While most MRSA cases can still be treated from a range of antibiotics, that may not always be the case, as the strains develop resistance over time.

"It's kind of like an arms race, and the bugs are winning," Blumberg said. "If you look at the number of new antibiotics that are being developed in the pipeline, it's very limited."

"We're at the point where we're starting to see organisms that are resistant to every antibiotic we have, and we're not going to get a lot of new ammunition," he said. "I don't think the public and policy makers are really aware — I don't think people are aware of how bad the situation is with multi-drug resistant organisms. We can't treat people because the organisms have become resistant to everything."

The study appears in the October issue of the CDC's journal Emerging Infectious Diseases.

This story was provided by MyHealthNewsDaily, a sister site to LiveScience. Follow MyHealthNewsDaily on Twitter @MyHealth_MHND. Find us on Facebook.