Artificial Cilia Mimic Micro Movement

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

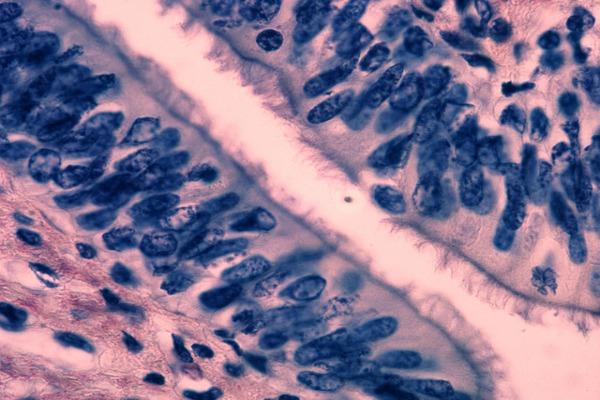

The microscopic, hair-like structures called cilia act like the engines of cellular biology. They use a coordinated wave motion to propel bacteria, clean out your lungs and even move eggs from the ovaries into the uterus. How cilia managed that coordination continued to confound, until a team of researchers built their own artificial version.

By assembling an basic cilia from biological building blocks, researchers from Brandeis University have developed a new approach to understanding how cilia works, which could lead to their implementation into micro-bots and other nanotech devices. "We've shown that there is a new approach toward studying the beating," said Associate Professor of Physics Zvonimir Dogic. "Instead of deconstructing the fully functioning structure, we can start building complexity from the ground up."

Previous experiments hoped to discover which component of cilia dictated that coordination by eliminating components of the cilia system one by one. Dogic and his team went the other route, building the cilia up from scratch one piece at a time.

The researchers built an experimental system comprised of three main components; microtubule filaments — tiny hollow cylinders found in both animal and plant cells, motor proteins called kinesin, which consume chemical fuel to move the microtubules and a bundling agent that causes those filaments to form into bundles.

The team found out that under a particular set of conditions these very simple components spontaneously organize into active bundles that beat in a periodic manner. In addition to observing the beating of isolated bundles, the researchers were also able to assemble a field of bundles that spontaneously synchronized their beating patterns into traveling waves.

Armed with this information, they hope to do further research to see how cilia can be used in other capacities outside the human body.

This story was provided by InnovationNewsDaily, a sister site to LiveScience. Follow InnovationNewsDaily on twitter @News_Innovation, or on Facebook.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus