More humans are growing an extra blood vessel in our arm that 'feeds' our hands, study shows

Picturing how our species might appear in the far future often invites wild speculation over stand-out features such as height, brain size, and skin complexion. Yet subtle shifts in our anatomy today demonstrate how unpredictable evolution can be.

Take something as mundane as an extra blood vessel in our arms, which going by current trends could be common place within just a few generations.

Researchers from Flinders University and the University of Adelaide in Australia have noticed an artery that temporarily runs down the center of our forearms while we're still in the womb isn't vanishing as often as it used to.

That means there are more adults than ever running around with what amounts to be an extra channel of vascular tissue flowing under their wrist.

"Since the 18th century, anatomists have been studying the prevalence of this artery in adults, and our study shows it's clearly increasing," says Flinders University anatomist Teghan Lucas.

"The prevalence was around 10 percent in people born in the mid-1880s compared to 30 percent in those born in the late 20th century, so that's a significant increase in a fairly short period of time, when it comes to evolution."

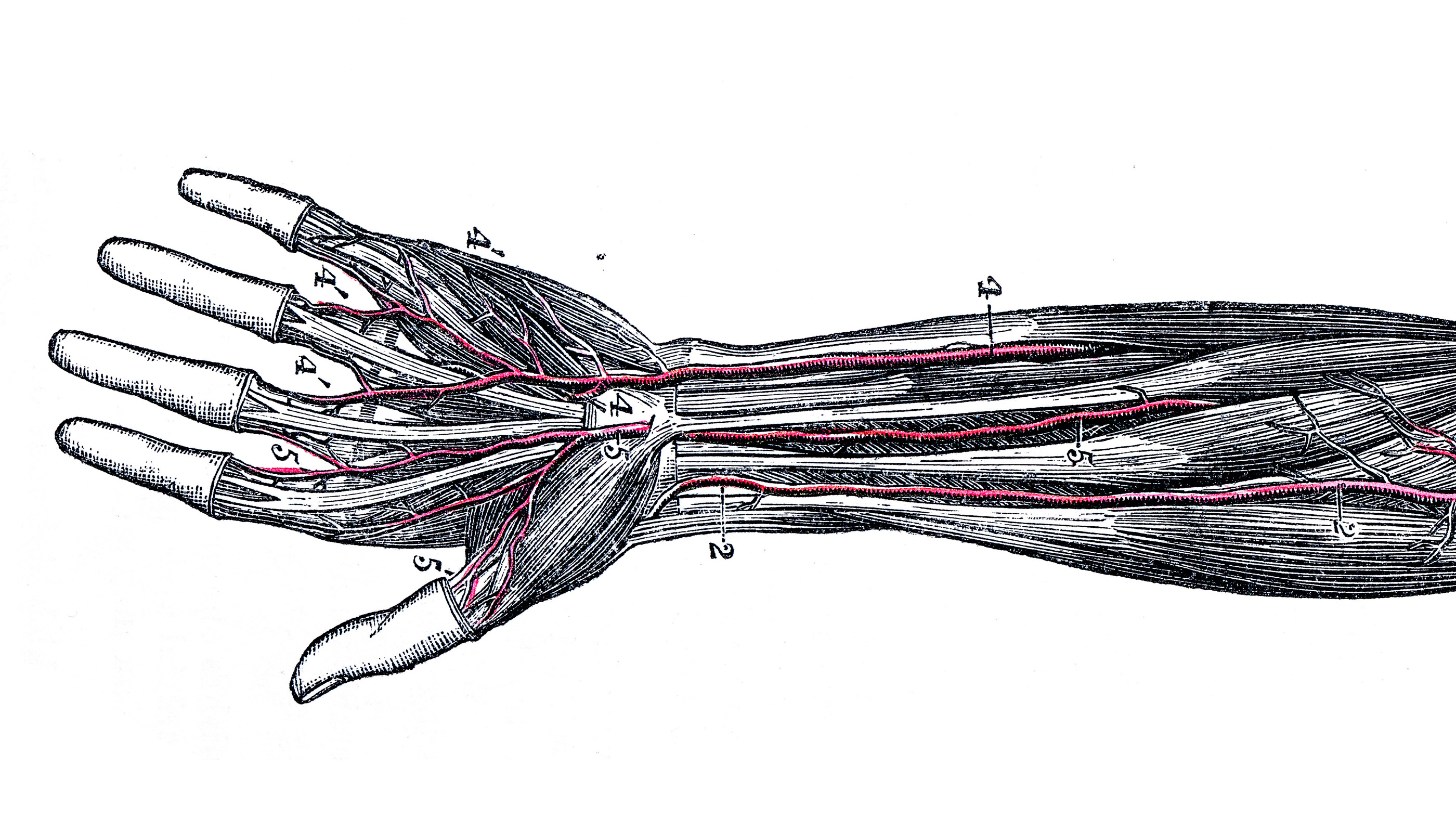

The median artery forms fairly early in development in all humans, transporting blood down the center of our arms to feed our growing hands.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

At around 8 weeks, it usually regresses, leaving the task to two other vessels – the radial (which we can feel when we take a person's pulse) and the ulnar arteries.

Anatomists have known for some time that this withering away of the median artery isn't a guarantee. In some cases, it hangs around for another month or so.

Sometimes we're born with it still pumping away, feeding either just the forearm, or in some cases the hand as well.

To compare the prevalence of this persistent blood channel, Lucas and colleagues Maciej Henneberg and Jaliya Kumaratilake from the University of Adelaide examined 80 limbs from cadavers, all donated by Australians of European descent.

The donors raged from 51 to 101 on passing, which means they were nearly all born in the first half of the 20th century.

Noting down how often they found a chunky median artery capable of carrying a good supply of blood, they compared the figures with records dug out of a literature search, taking into account tallies that could over-represent the vessel's appearance.

The fact the artery seems to be three times as common in adults today as it was more than a century ago is a startling find that suggests natural selection is favoring those who hold onto this extra bit of bloody supply.

"This increase could have resulted from mutations of genes involved in median artery development or health problems in mothers during pregnancy, or both actually," says Lucas.

We might imagine having a persistent median artery could give dextrous fingers or strong forearms a dependable boost of blood long after we're born. Yet having one also puts us at a greater risk of carpal tunnel syndrome, an uncomfortable condition that makes us less able to use our hands.

Nailing down the kinds of factors that play a major role in the processes selecting for a persistent median artery will require a lot more sleuthing.

Whatever they might be, it's likely we'll continue to see more of these vessels in coming years.

"If this trend continues, a majority of people will have median artery of the forearm by 2100," says Lucas.

This rapid rise of the median artery in adults isn't unlike the reappearance of a knee bone called the fabella, which is also three times more common today than it was a century ago.

As small as these differences are, tiny microevolutionary changes add up to large-scale variations that come to define a species.

Together they create new pressures themselves, putting us on new paths of health and disease that right now we might find hard to imagine today.

This research was published in the Journal of Anatomy.

This article was originally published by ScienceAlert. Read the original article here.

Mike McRae is a part-time Journalist at ScienceAlert. He has been telling science stories in one form or another for more than 20 years, and expertly navigates a broad range of subjects, from health and neuroscience to the weirdness of quantum physics. From classroom teacher to journalist, Mike has contributed to the CSIRO's magazines, The Guardian, the ABC and Australian Financial Review. He is the author of popular science books "Tribal Science: Brains, Beliefs," and "Bad ideas and Unwell: What Makes a Disease a Disease?" Mike is slowly building a collection of cephalopod tattoos on his right arm and swears there's still room for a nautilus or two.