Dark Matter Could Be the Life of the Party for Starless Planets

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

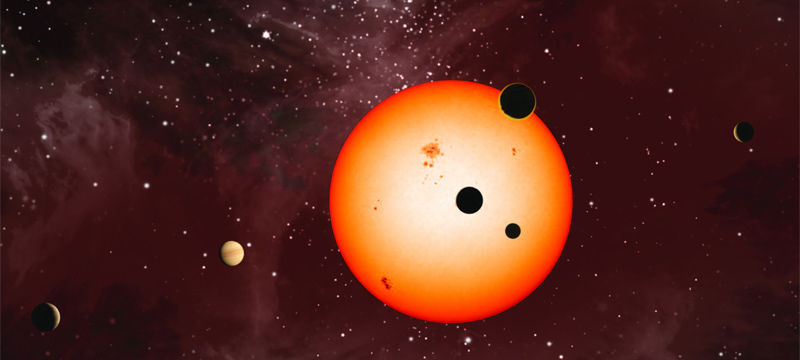

There may be worlds that float through intergalactic space in darkness without stars to warm them. Such lonely planets, endlessly adrift in night, might seem too cold and dark to ever serve as homes for life.

But mysterious, unseen dark matter could help make warm these starless planets and make them habitable, a new study suggests. The idea may be a bit out there, but it’s not impossible, researchers say.

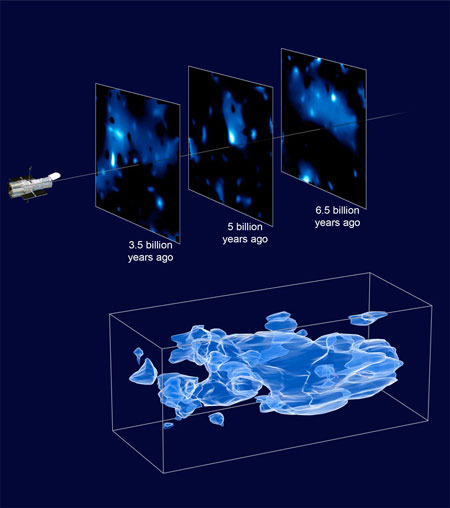

Scientists think invisible, as-yet-unidentified dark matter makes up about 85 percent of all matter in the universe. They know it exists because of the gravitational effects it has on galaxies. [Video: Dark Matter in 3-D]

Warmth from dark matter?

Among the leading candidates for what dark matter is are massive particles that only rarely interact with normal matter. These particles could be their own antiparticles, meaning they annihilate each other when they meet, releasing energy.

If these dark matter particles do exist, they could get captured by a planet's gravity and unleash energy that could warm that world, reasoned physicist Dan Hooper and astrophysicist Jason Steffen at the Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory.

Although this amount of energy would be negligible when it comes to Earth — a few megawatts at most — they calculate that larger, rocky "super-Earths" in regions with high densities of slow-moving dark matter could be warmed enough to keep liquid water on their surfaces, even in the absence of additional energy from starlight or other sources.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The density of dark matter is expected to be hundreds to thousands of times greater in the innermost regions of the Milky Way and in the cores of dwarf spheroidal galaxies than it is in our solar system.

"We are talking about rare and special environments, but not implausible ones," Hooper told SPACE.com. [The Strangest Alien Planets]

The scientists surmised that on planets in those areas, it may be that dark matter rather than light makes it possible for life to develop and survive. After all, on Earth, there is life virtually wherever there is water.

"You can have all the basic elements you need for organic life without a star," Hooper said.

Dark matter: Better than a star

Indeed, dark matter could keep the surfaces of such warm for trillions of years, outliving all regular stars, the researchers suggested. Given their extremely long lifetimes, such planets may prove to be the ultimate bastion of life in our universe, they added. For comparison, the universe is estimated to be 13.7 billion years old.

"I imagine 10 trillion years in the future, when the universe has expanded beyond recognition and all the stars in our galaxy have long since burnt out, the only planets with any heat are these ones here, and I could imagine that any civilization that survived over this huge stretch of time would start moving to these dark-matter-fueled planets," Hooper said.

However, the scenario lies in the more optimistic end of models calculating how dark matter behaves.

Also, assuming that such planets exist, "there probably aren't many of them," Hooper cautioned. Also, current planet-hunting missions focus on worlds that starlight can help detect — dark-matter-fueled planets not only might lie far away from any stars, but are not especially hot, making them difficult to see. "I don't see us discovering planets like this anytime soon," he said.

The scientists detailed their findings online March 25 in a paper submitted to The Astrophysical Journal.

Follow SPACE.com contributor Charles Q. Choi on Twitter @cqchoi. Visit SPACE.com for the latest in space science and exploration news on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

This story was provided by SPACE.com, a sister site to LiveScience.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus