Sex Differences Found in Stem Cells

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

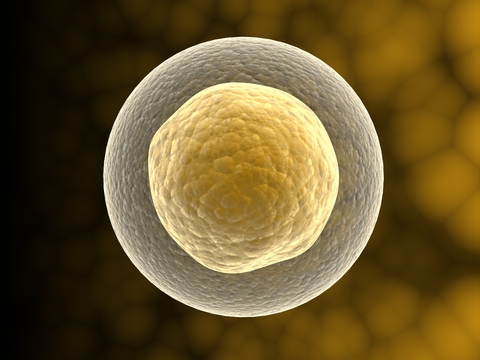

Stem cells taken from the muscles of female mice are better at regenerating tissue than those taken from male mice, a new study finds.

This revelation could have a major impact on the development of stem cells as therapies for many diseases and conditions.

The discovery came when scientists who had done many studies with these muscle stem cells realized that all of the ones they had used came from female mice. They then did an experiment with both male and female cells to see if they would perform similarly.

Muscle breakdown

Embryonic stem cells can divide to become any type of cell in the body. Muscle stem cells, which come from adult tissue instead of an embryo, are more specialized and limited in what they can become.

The researchers injected stem cells from healthy mice into mice that had a disease analogous to the human genetic disease Duchene muscular dystrophy, which affects one in every 3,500 to 5,000 young boys in the United States, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

People with this disease lack a protein called dystrophin that gives muscle cells structure.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

“Their muscle breaks down and is replaced by fat,” said study co-author Bridget Deasy of the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine. Patients usually die from cardiac or respiratory problems as fat replaces muscle tissue in the heart and diaphragm.

Boys are generally diagnosed with the disease by the time they are five years old, and are wheelchair-bound by their early teens; few live past the age of 25.

One way scientists are looking at to treat diseases like this is cell transplantation.

Male vs. female

After injecting the mice with the stem cells, the researchers measured the cells’ ability to regenerate muscle fibers that contained dystrophin. The researchers, whose work is published in the April 9 issue of the Journal of Cell Biology, found that female cells produced many more fibers than male cells.

“Regardless of the sex of the host, the implantation of female stem cells led to significantly better skeletal muscle regeneration,” said the study’s senior author Johnny Huard, also of the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine.

The sex-related differences seemed to come from the cells’ stress responses. When cells are transplanted, the tissue becomes inflamed and the new cells are exposed to free radicals, which causes the male cells to differentiate, or stop making more of themselves.

“When you differentiate, you’re done,” Deasy told LiveScience. “That’s the end of the line for a stem cell.”

Deasy and her colleagues aren’t sure what is behind the sex-related differences, but they believe the differences will hold true in other stem cells, including those from humans.

“I think when people start looking for it, they’ll find it,” Deasy said. “They’ll be a difference.”

Andrea Thompson is an associate editor at Scientific American, where she covers sustainability, energy and the environment. Prior to that, she was a senior writer covering climate science at Climate Central and a reporter and editor at Live Science, where she primarily covered Earth science and the environment. She holds a graduate degree in science health and environmental reporting from New York University, as well as a bachelor of science and and masters of science in atmospheric chemistry from the Georgia Institute of Technology.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus