Grave Reveals Violent Death of Ancient Family

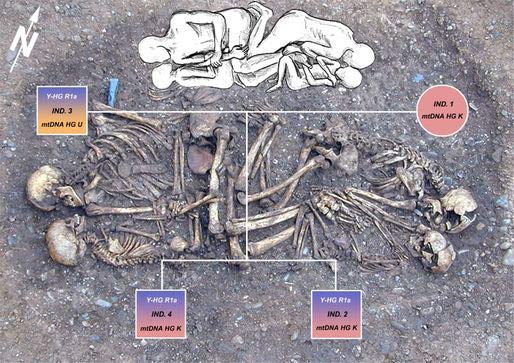

A grave with the remains of a mother and father huddled together with two sons has been dated to 4,600 years ago and marks the oldest genetic evidence for a nuclear family, researchers say.

The individuals were carefully arranged in their graves to denote they were part of a biological family, the researchers say. Wounds on the remains suggest the parents and kids were defending themselves against a violent raid, involving stone axes and arrows, at the time of their deaths.

The family grave is one of four burials discovered in 2005 near Eulau, Germany. All together, the burials hold 13 individuals, including adults ages 30 years and older, and children ranging from newborn to 10 years old at death.

The results, detailed this week in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, suggest biological relationships were the focus of social organization in the Late Stone Age society.

Close-knit families

Only recently did Wolfgang Haak of the University of Adelaide and his colleagues extract and analyze DNA from the ancient remains. Not all of the individuals contained intact, preserved DNA, so the researchers were only able to map out the genetic relationships among individuals in two of the graves (including that of the nuclear family), along with other details such as age.

The genetic evidence matched the positioning of the buried individuals. For instance, in the grave of the family of four, the mother was curled up on her side facing her son and the father was also on his side facing the other son with their arms interlinked. One of the sons was between 4 and 5 years old, while the other was 8 to 9 years old.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

In the other grave, two individuals, ages 9 and 10, were likely siblings or at least maternally related. Unlike the facing parents and sons in the four-person grave, the adult female buried with the siblings was not facing the two children.

Genetic analysis showed she was not the kids' mother. Instead, the researchers suggest the woman was an aunt on the father's side of the family or a step-mother to the buried children.

This woman along with one of the sons in the nuclear-family grave had signs of skull fractures. Signs of defensive injuries were found on the forearms and hands of other buried individuals.

"By establishing the genetic links between the two adults and two children buried together in one grave, we have established the presence of the classic nuclear family in a prehistoric context in Central Europe," Haak said.

He added, "Their unity in death suggests a unity in life. However, this does not establish the elemental family to be a universal model or the most ancient institution of human communities."

Ancient marriages

The researchers gleaned even more information about the family by analyzing strontium isotopes from teeth. (Isotopes are atoms of a particular element that have the same number of protons but a different number of neutrons in the nucleus.) Since strontium from food is incorporated into a person's teeth over time, the relative amounts of different strontium isotopes can link the ancient remains with different regions.

The results showed that the females spent their childhoods in different regions from the males and children in the grave, suggesting the females "married out," moving to the location of the males for marriage, the researchers say.

"Such traditions would have been important to avoid inbreeding and to forge kinship networks with other communities," said Alistair Pike, head of Archaeology at the University of Bristol and co-director of the project.

- Top 10 Ways We Deal with the Dead

- History's Most Overlooked Mysteries

- Quiz: Artifact Wars

Jeanna Bryner is managing editor of Scientific American. Previously she was editor in chief of Live Science and, prior to that, an editor at Scholastic's Science World magazine. Bryner has an English degree from Salisbury University, a master's degree in biogeochemistry and environmental sciences from the University of Maryland and a graduate science journalism degree from New York University. She has worked as a biologist in Florida, where she monitored wetlands and did field surveys for endangered species, including the gorgeous Florida Scrub Jay. She also received an ocean sciences journalism fellowship from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. She is a firm believer that science is for everyone and that just about everything can be viewed through the lens of science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus