Dinosaur Demise Theory Is Soaking Wet

Dinosaur doomsday was wetter than scientists have thought, according to new images of the crater where the space rock that likely killed the dinosaurs landed.

Sixty-five million years ago the asteroid struck the coast of the Yucatan Peninsula, and most scientists think this event played a large role in causing the extinction of 70 percent of life on Earth, including non-avian dinosaurs.

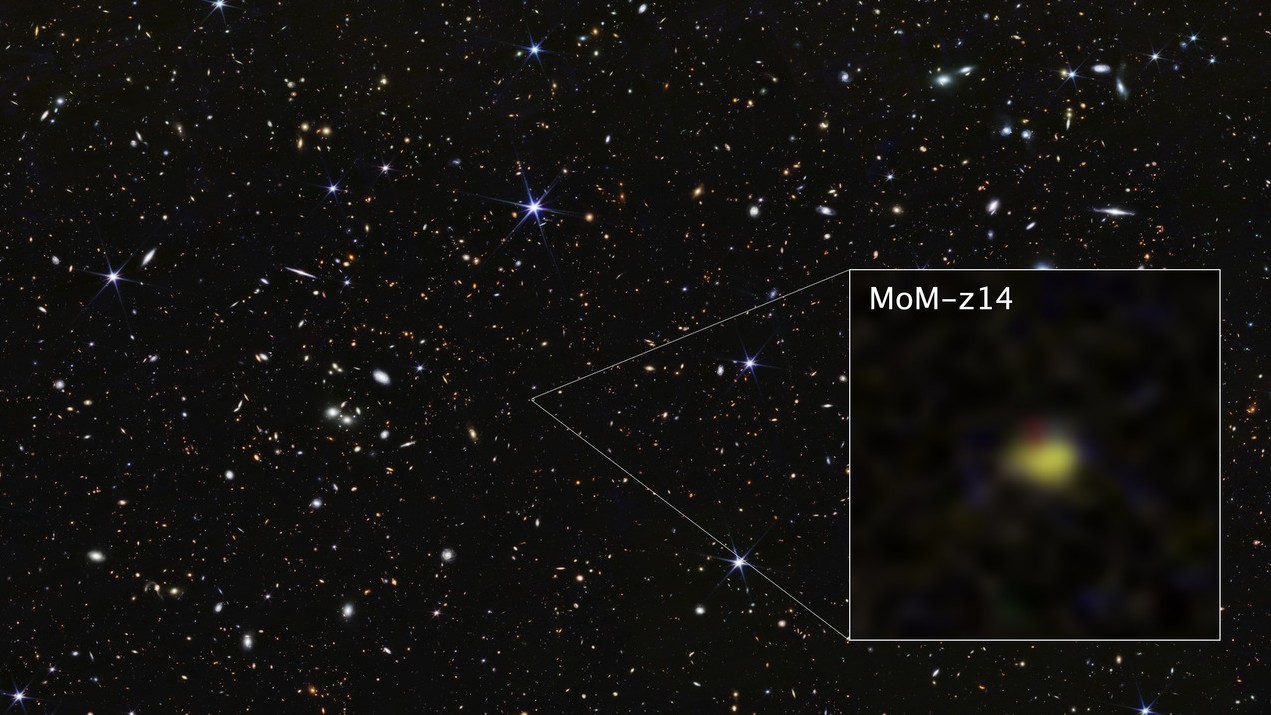

Geophysicists now have created the most detailed 3-D seismic images yet of the mostly submerged Chicxulub impact crater. The data reveal that the asteroid landed in deeper water than previously assumed and therefore released about 6.5 times more water vapor into the atmosphere.

The images also show the crater contained sulfur-rich sediments that would have reacted with the water vapor to create sulfate aerosols. These compounds in the atmosphere would have made the impact deadlier by cooling the climate and producing acid rain.

"The greater amount of water vapor and consequent potential increase in sulfate aerosols needs to be taken into account for models of extinction mechanisms," said Sean Gulick, a geophysicist at the University of Texas at Austin who led the study.

The findings will be published in the February 2008 issue of the journal Nature Geosciences.

The asteroid impact alone was probably not responsible for the mass extinction, Gulick said. More likely, a combination of environmental changes over different time scales took their toll.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Many large land animals, including the dinosaurs, might have baked to death within hours or days of the impact as ejected material fell from the sky, heating the atmosphere and setting off firestorms. More gradual changes in climate and acidity might have had a larger impact in the oceans.

If there was more acid rain than scientists had previously calculated, that could help explain why many smaller marine creatures were affected, because the rain could have turned the oceans more acidic.

There is some evidence that marine organisms more resistant to a range of pH survived, while more sensitive creatures did not.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus