Russia's 'Dyatlov Pass' conspiracy theory may finally be solved 60 years later

In the infamous 'Dyatlov Pass incident,' nine young hikers died under mysterious circumstances. Now, there's a scientific explanation.

In January 1959, a group of nine young hikers — seven men and two women — trudged through Russia's snowy Ural Mountains toward a peak locally known as "Dead Mountain." The hikers pitched their tents at the base of a small slope, as an intensifying blizzard chilled the night air to minus 19 degrees Fahrenheit (minus 25 degrees Celsius). They never made it to their next waypoint.

It took nearly a month for investigators to find all nine bodies scattered amid the snow, trees and ravines of Dead Mountain. Some of the hikers died half-dressed, in just their socks and long underwear. Some had broken bones and cracked skulls; some were missing their eyes; and one young woman had lost her tongue, possibly to hungry wildlife. Their tent, half-buried in the snow and apparently slashed open from the inside, still held some of the hikers' neatly-folded clothes and half-eaten provisions.

All nine hikers had died of hypothermia after being cast into the cold "under the influence of a compelling natural force," a Russian investigation concluded at the time. But the specifics of the "compelling" force behind the now-infamous "Dyatlov Pass incident" (named for one of the hikers, Igor Dyatlov) have long remained a mystery, and given rise to one of the most enduring conspiracy theories in modern Russian history.

Related: 10 Times HBO's 'Chernobyl' got the science wrong

Everything from aliens to abominable snowmen have been implicated in the mystery since it rose to cultural prominence in the 1990s, following a retired official's account of the investigation (The Atlantic's Alec Luhn has summarized some of the most peculiar theories.) But now, a study published Thursday (Jan. 28) in the Nature journal Communications Earth & Environment provides the first scientific evidence behind a much more banal hypothesis: A small avalanche, triggered under unusual conditions, pummeled the hikers as they slept, then forced them to flee their tent into the cold, dark night.

"We do not claim to have solved the Dyatlov Pass mystery, as no one survived to tell the story," lead study author Johan Gaume, head of the Snow and Avalanche Simulation Laboratory at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Lausanne, told Live Science. "But we show the plausibility of the avalanche hypothesis [for the first time]."

Mystery in the snow

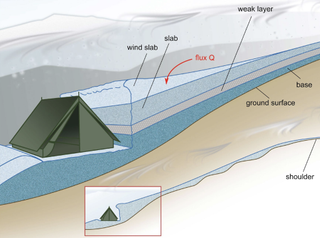

The avalanche hypothesis is not new; two federal Russian investigations (completed in 2019 and 2020) also concluded that the hikers were most likely driven from their tents by a slab avalanche — that is, an avalanche that occurs when a slab of snow near the surface breaks away from a deeper layer of snow, and it slides downhill in blocky chunks. However, this hypothesis hasn't been widely accepted by the public, the new study noted, because neither investigation offered a scientific explanation for some of the incident's stranger details.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"The slab avalanche theory was criticized due to four main counterarguments," Gaume said.

Related: Cracked bones reveal cannibalism by doomed Arctic explorers

First and foremost, there was no sign of an avalanche when rescuers arrived at the campsite 26 days after the hikers went missing. Second, the slope where the hikers built their camp had an incline of less the 30 degrees, which is typically considered the minimum angle for an avalanche to occur, Gaume said. Third, there's evidence that the hikers fled their tents in the middle of the night, meaning the avalanche was triggered hours after the highest risk event, when the hikers built their camp — a process that involved cutting into the face of the slope to create a flat surface below their tent and a sheer wall of snow next to it (a common practice at the time, the study authors wrote). Finally, some of the hikers had sustained head and chest injuries that avalanches usually don't cause, Gaume said.

In their paper, Gaume and study co-author Alexander Puzrin, a researcher at the Institute for Geotechnical Engineering in Zurich, Switzerland, set out to address each of these critiques. They studied records from the time of the Dyatlov incident to recreate the environmental conditions that the hikers most likely faced on the night of their deaths, and then used a digital avalanche model to test whether a slab avalanche could have plausibly occurred under those conditions.

The team's analysis showed that the avalanche hypothesis stands up to every counterargument.

A 'brutal force of nature'

In their study, the researchers learned that the angle of the slope near the hiker's campsite was actually steeper than previous reports indicated; the slope angle measured 28 degrees, compared with the area's average slope angle of 23 degrees. Subsequent snowfalls in the weeks after the incident could have smoothed this angle, making the slope appear smaller while also covering signs of an avalanche, the team wrote. That detail took care of counter-argument number one.

As for the second, while 30 degrees is considered the standard slope angle at which slab avalanches can occur, this is not a hard rule, the researchers wrote; in fact, there's evidence of avalanches occurring on slopes with angles as little as 15 degrees. A key factor is the friction value between the upper slab layer (the one that falls) and the base layer (the one that stays in place). The base of the snowpack at the Dyatlov campsite was composed of depth hoar, or "sugar snow" — a type of grainy, crystallized ice that often increases the risk of avalanches, the team wrote. This grainy base layer could have easily helped facilitate a slab avalanche, even at a 28-degree incline.

As for the delay between the hikers cutting into the slope and the avalanche tumbling onto their tents? This could be explained by strong winds that gradually blew more and more snow onto the top of the slope near the team's campsite. Conditions on the mountain were extremely windy, and snow may have accumulated above the tent for as many as 9.5 to 13.5 hours before the upper slab finally gave way, the team's models showed.

Related: The 10 deadliest natural disasters in history

This leads to the final counterargument: the injuries. Some hikers were found with cracked ribs and skulls — injuries more in line with a car accident than an avalanche. However, the supposed slab avalanche at Dyatlov Pass was far from typical. Rather than standing in the direct path of the avalanche, the hikers would have been lying flat on their backs as they slept, with the snow rushing down on top of them over the small ledge they cut into the slope.

"Dynamic avalanche simulations suggest that even a relatively small slab [of snow] could have led to severe but non-lethal thorax and skull injuries, as reported by the post-mortem examination," the researchers wrote.

The team's models showed that, under specific environmental conditions, a slab avalanche could have plausibly toppled onto the Dyatlov group as they slept, long after they cut into the slope to build their camp. The crushing snow all but flattened the tent, cracking bones and forcing the hikers to hastily cut their way out of their snowy sarcophagus, dragging their wounded comrades behind as they attempted to survive the night in the open air. Sadly, none did.

While this paper doesn't explain every facet of the Dyatlov mystery, it does provide the first scientific proof that at least one popular hypothesis — the avalanche hypothesis — is plausible, the authors concluded. That explanation may be far less exciting than aliens or yetis, but for Gaume, the banality of the avalanche hypothesis reinforces something more important: the human aspect of the catastrophe.

"When [the hikers] decided to go to the forest, they took care of their injured friends — no one was left behind," Gaume said. "I think it is a great story of courage and friendship in the face of a brutal force of nature."

Originally published on Live Science.

Brandon is the space/physics editor at Live Science. His writing has appeared in The Washington Post, Reader's Digest, CBS.com, the Richard Dawkins Foundation website and other outlets. He holds a bachelor's degree in creative writing from the University of Arizona, with minors in journalism and media arts. He enjoys writing most about space, geoscience and the mysteries of the universe.

Most Popular