Fanged Fish Drugs Attackers with Heroin-Like Venom

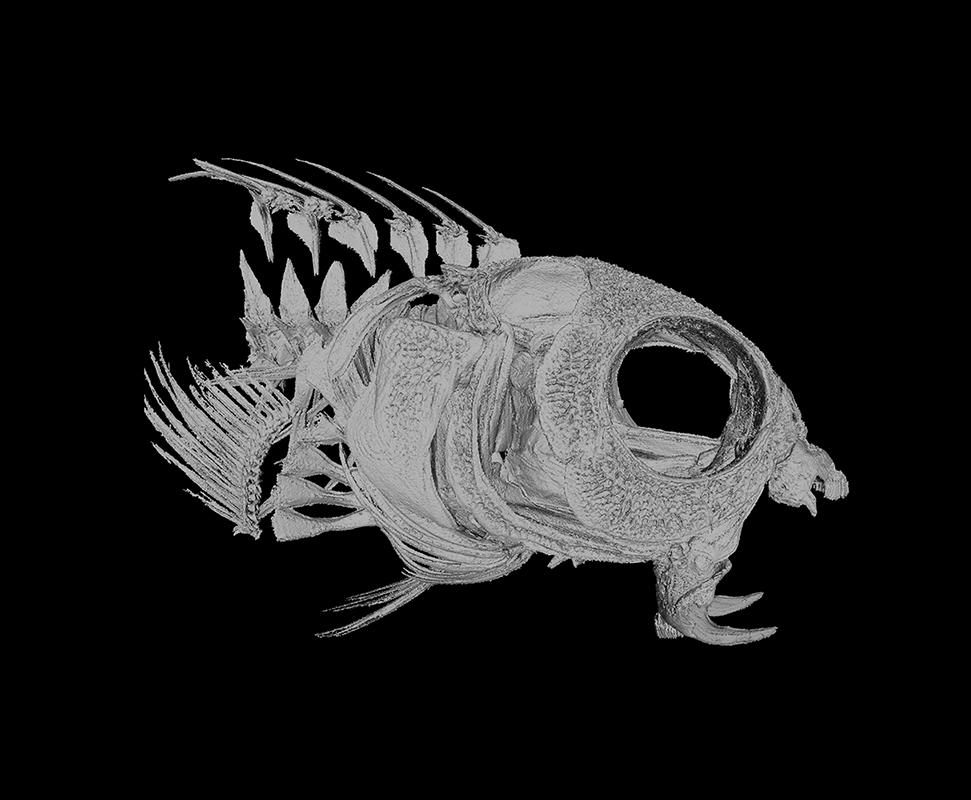

Fang blennies — colorful Pacific region fish — in the Meiacanthus genus may be small, but they pack a very serious bite.

There are five genera of fang blennies, and all sport large, hollow canine fangs on their lower jaws, which slot neatly into holes inside the upper part of their mouths. But only species in the Meiacanthus genus have fangs that are grooved, connected to special glands and capable of delivering a dose of venom.

In a new study, researchers analyzed venom samples from the fishes' tiny fangs. They found a chemical cocktail loaded with opioid peptides that perform like morphine or heroin, making blenny attackers dizzy and sluggish when bitten. The cocktail is unique to the fang blenny, the researchers said. They added that the compounds, which are recognized for pain-inhibiting properties, could be used to develop novel painkillers. [Pick Your Poison: 7 Creatures With Healing Venom]

Fang blennies, also known as saber-toothed blennies, were already known to thwart predators with their venom. Scientists reported observing blennies engulfed by the mouths of larger fish, which then experienced a "quivering of the head" and spat the blenny out unharmed, the study authors wrote.

The use of venom purely for defensive purposes is highly unusual in the animal kingdom, the researchers said. However, the presence of venom in fish is not unusual at all. Over 2,000 fish species living in marine and freshwater environments are venomous, though the overwhelming majority — about 95 percent — deliver their toxins through spines that protrude from their backs.

A unique chemical blend

When the scientists tested venom samples from the fang blennies, they noticed it produced a very different effect from venom delivered by fish through spines, which usually sparks excruciating pain out of proportion to the initial puncture. They analyzed fang blenny venom components, noting a combination that would likely dull a predator's coordination and affect its ability to swim, enabling the blenny to escape.

Fang blennies' evasive techniques are so successful they inspired copycats — species that resemble venomous blennies, but don't have any venom.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

These "deceitful imitations," the study authors said, are practicing mimicry, an evolutionary strategy that drives species to look like other species sharing their habitat that have better defenses against predators — such as toxins.

"Other fish mimic blennies to get the benefit of larger fish avoiding fang blennies because of their toxicity," study co-author Bryan Fry, a biochemist and molecular biologist and an associate professor at the Australian Academy of Science, told Live Science in an email.

"The mimicry aspect is an incredibly complex angle, and there is an astounding amount going on just with this one aspect," Fry said.

But time may be running out for reef fish like the fang blennies. Warming oceans and rising acidification levels threaten the reefs that blennies and many other species call home. A recent survey of the Great Barrier Reef warned that sizable parts of the reef were dead or dying, after it experienced severe coral bleaching following record-breaking high temperatures in 2016.

"This study is an excellent example of why we need to protect nature," Fry said.

"If we lose the Great Barrier Reef, we will lose animals like the fang blenny and its unique venom that could be the source of the next blockbuster pain-killing drug," he added.

The findings were published online today (March 30) in the journal Current Biology.

Original article on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is a science journalist and author of "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind-Control" (Hopkins Press). She formerly edited for Scholastic and was a channel editor and senior writer for Live Science. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to LS, she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in NYC. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post, How It Works Magazine and CNN.