Crocodile Carving Played Ritual Role in Ancient Mesoamerican City

A centuries-old stone crocodile carving used in Mesoamerican rituals was recently discovered in Mexico, offering clues about an ancient city's ceremonial practices, and its relationship with a larger city nearby.

Archaeologists found the slab of carved rock in what is now Oaxaca, near a temple in the ruins of the city Lambityeco, which archaeologists first uncovered in the 1960s and dates back between 500 and A.D. 850. Early excavations at the site decades ago had revealed two palaces; frescoes in one of them hinted at close ties with a larger city in the area called Monté Albon, researchers from the Field Museum in Chicago, who investigated Lambityeco for the past four years, said in a statement.

Their work yielded hints that Lambityeco may have begun distancing itself from its more powerful neighbor at one point, with scientists unearthing evidence of changes to important structures and their access routes. [The 7 Most Mysterious Archaeological Finds on Earth]

Buried and barricaded

The crocodile carving was found after clearing and following a hidden path that had been deliberately barricaded, perhaps as Lambityeco's inhabitants sought to reshape their city to reflect and celebrate their own power and influence rather than Monté Alban's, according to Gary Feinman, one of the team's lead archaeologists and a curator of Mesoamerican anthropology at the Field Museum.

Feinman told Live Science that the group was looking closely at parts of the site related to civic and ritual uses. They were especially interested in the pre-Hispanic ball court, a type of space that was both recreational and ceremonial, and which is recognized to have particular significance in Mesoamerican society.

During the last season's work, in 2015, when the archaeologists excavated the first part of the ball court, they noticed something peculiar — access to the court and its overall layout appeared to have been changed from its original construction and while it was still in use.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"The stairway leading out of the ball court was destroyed, and there was river gravel piled to block access to the stairway," Feinman said.

Clearing a path

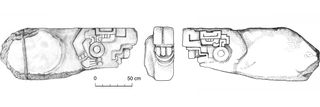

Intrigued, the researchers investigated and found a path with large jars arranged along it. When they returned in 2016 to see what else they could find along this path, they discovered the crocodile carving, up against a building on the east side of a plaza.

Artifacts near the carving showed that it served a ritual purpose, Feinman explained. "In front of it was charcoal, pieces of burnt human skull, broken ceramics used as incense burning vessels," he said.

Clearly it was being used — but the archaeologists doubted that it was in its original position, as the stone was upside down and wasn't well-attached to the building next to it, he said. [In Photos: Amazing Ruins of the Ancient World]

"I suspect that because the stone was carved on three sides that it was a balustrade marking the beginning of one side of a stairway," Feinman said, adding it was a stairway that was later destroyed.

"It looked like they flipped the crocodile stone and reversed it, and left it leaning against the platform, which they then remodeled without a stairway," he said.

The blocked entrance, the path, the jars and the crocodile stone may have once been part of a ceremony that began at the ball court and ended at the temple building where the carved crocodile was found, Feinman told Live Science.

Breaking away"We think that when the ball court was first constructed, some kind of ritual procession went out past the jars, into the plaza, and up to the building where we found the crocodile stone," Feinman said. "The ball court was seen as access to the underworld. You'd come out of the underworld, get food from the jars, go up to the plaza — the level of earth — and up to the temple, where you accessed the supernatural world. That clearly changed when they remodeled," he added.

Lambityeco's ball court was originally a near-perfect copy of Monté Alban's. But the archaeologists found that about 150 years after the ball court was built, it was modified to shorten it and to change the entrance from the north to the northeast corner — which altered the former processional path to the temple. According to Feinman, this may have reflected Lambityeco's leaders' attempts to declare their own importance.

"We think that when the civic-ceremonial core of the site was laid out [in] about 500 A.D., there were strong connections between the people who were in charge in Lambityeco and the people who ruled the valley's largest city, Monté Alban," Feinman said.

But after 100 to 150 years, that relationship may have changed, according to Feinman. "Possibly the changes that took place in Lambityeco were not only to differentiate it, but also may have given more attention or focus or power to local rulers," he said.

Interestingly, while crocodiles were widely associated with the Mesoamerican calendar and held an important role in creation myths, Feinman pointed out that it's unlikely that people living in Oaxaca would ever have seen a living crocodile. As the valley was landlocked, this stone carving of the toothsome river beast was likely the closest that many of Lambityeco's inhabitants ever came to the seeing the real thing.

Original article on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is an editor at Scholastic and a former Live Science channel editor and senior writer. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology, and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to Live Science she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post and How It Works Magazine.