Black Magic: 6 Infamous Witch Trials in History

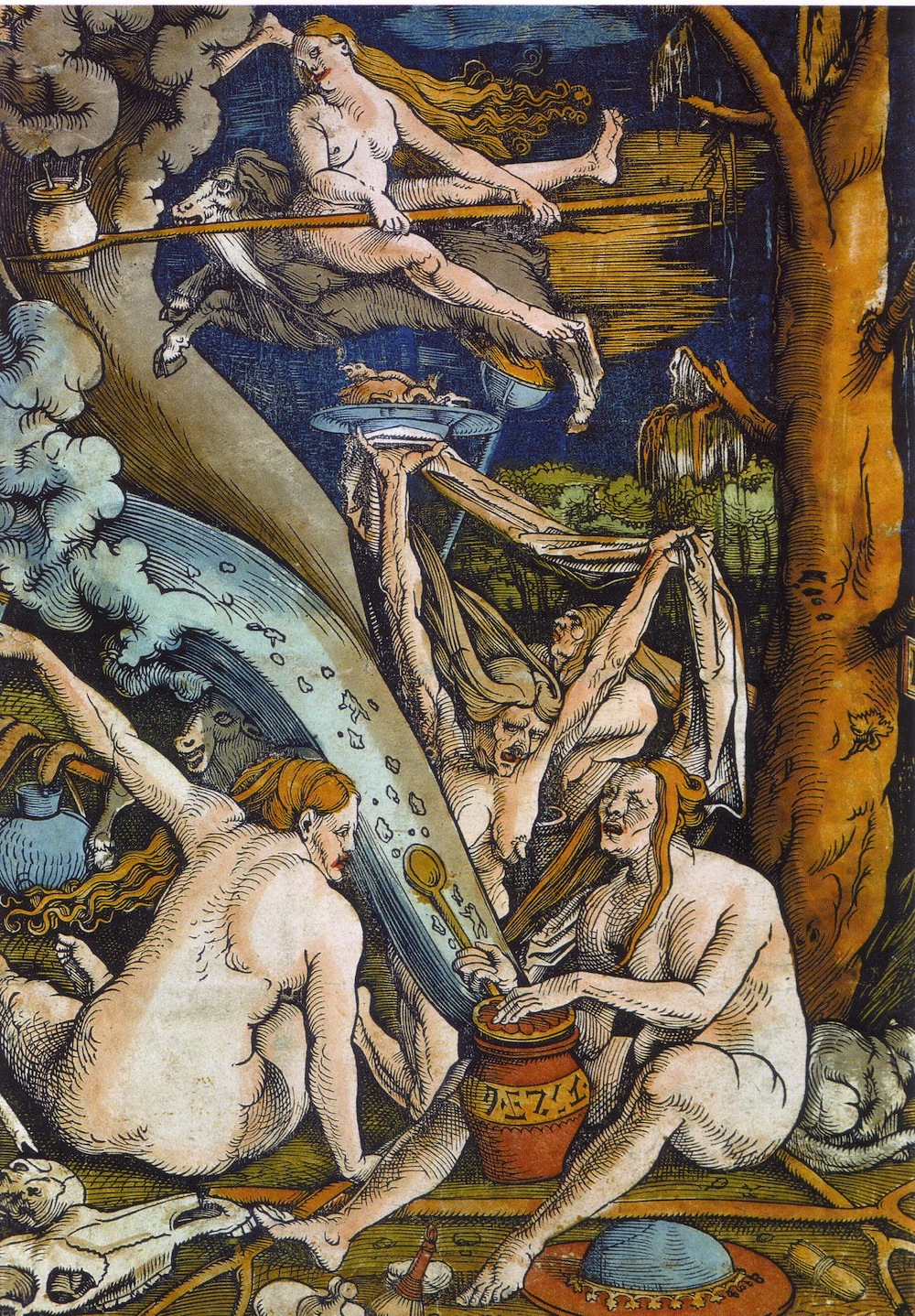

Toil and trouble

Although the persecution of alleged witches took place in Christian Europe during the medieval period, it reached its peak during the religious wars of the 16th and 17th centuries. In that period, laws in many Catholic and Protestant countries brutally enforced the belief that witchcraft was the work of the devil.

Historians estimate that between 40,000 and 60,000 people were executed for witchcraft in Europe and the American colonies from the 15th to the early 18th centuries, and up to 75 percent of the victims were women.

Here are six of the most infamous witch trials in Europe and the United States.

Weather witches

Denmark was the scene of some of the earliest witch hunts in Europe. These accusations were often linked to magical conspiracies about the weather.

In one of the earliest recorded witch trials, in 1543, a woman named Gyde Spandemager, the wife of a merchant, was accused of casting spells that caused the winds to fail as Danish warships pursued an enemy Dutch fleet.

After being tortured, Spandemager confessed to witchcraft and named several other people as accomplices, who were then also tortured and put on trial. None of the others confessed, but authorities executed Spandemager by burning her at the stake.

Several celebrated witch trials in Denmark resulted in the executions of hundreds of people. Historians estimate that around 250 alleged witches were executed in the Danish district of Jutland alone during the 1600s.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

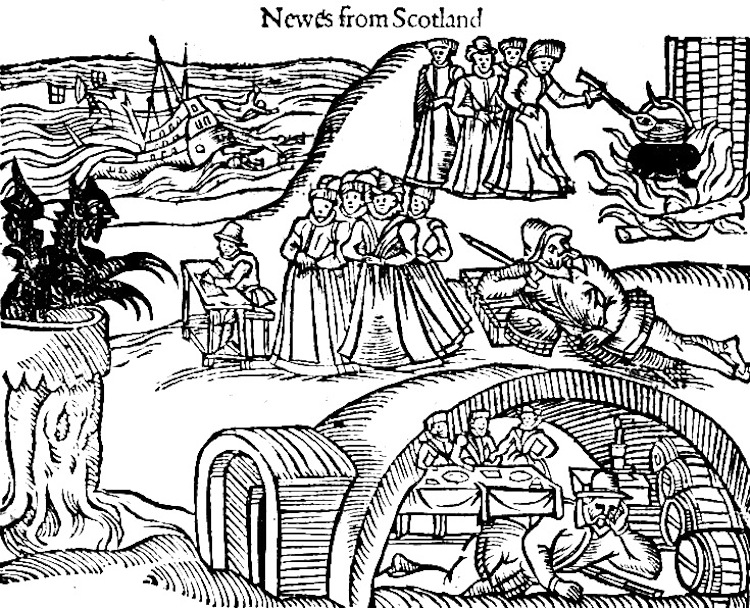

Bewitching the waves

The Danish witch panic spread to Scotland in 1589, when Princess Anne of Denmark left by ship to marry King James VI of Scotland, who would later become James I of England.

After storms almost wrecked the ship carrying the princess to Scotland, the royal couple met in Norway to be married. But storms also struck the ship carrying the newlyweds back to Scotland.

When the Danish minister of finance was accused of underequipping the ships for the storms, he then accused a group of women in Copenhagen of casting spells to raise the bad weather.

One of the suspects, a woman named Anna Koldings named five other women as witches, who all admitted under torture they had sent the devil to climb up the keel of the ship carrying the princess. Koldings and 12 other women were burned at the stake in 1590.

Scotland's witch scare

The Danish witch trial and the alleged magical attack on his bride spurred King James to start the first of five "great witch hunts" in Scotland.

In 1590, James set up his own tribunal to investigate accusations of witchcraft in the town of North Berwick, near Edinburgh. By 1592, the tribunal had tortured and put on trial approximately 70 suspected witches, including some Scottish nobles.

Many were burned at the stake, including Agnes Sampson, an elderly and respectable woman who denied, while under severe torture, that she was a witch. Finally, however, she broke down and confessed to plotting with the devil to kill the king.

The astronomer and the witch

The German astronomer and mathematician Johannes Kepler (1571-1630) helped prove that the Earth orbits the sun, but his family suffered under the superstitions of the time.

In 1615, Kepler's 68-year-old mother, Katharina, was accused of witchcraft by neighbors in her hometown of Leonberg. The accusers claimed Katharina used spells to make her enemies ill and that she could transform herself into a cat.

Although Katharina was never put on trial, her investigation lasted six years, including 14 months when she was chained to the floor of a prison cell in an effort to get her to confess. Johannes Kepler loyally defended his mother throughout her ordeal, and Katharina was set free in 1621 — but died just six months later.

Salem witch trials

The Puritan founders of English colonies in the Americas brought Europe's ideas about witchcraft with them, and in 1692, witch hysteria reached its peak in America with the infamous Salem witch trials.

The trials began after a group of young girls in Salem Village began having fits of contortions and screaming, and accused several local women of bewitching them.

A special court was set up to hear the cases, and by September 1692, more than 150 men, women and children had been accused of witchcraft. The town executed 19 of the people by hanging.

But public opinion turned against the witch trials, and in 1711, a different Massachusetts court annulled the guilty verdicts against those in Salem still accused of witchcraft.

The witch who got away

One of the last witch trials in England was that of Jane Wenham in Hertfordshire, in 1712. Following a quarrel, a local farmer accused Wenham of witchcraft, claiming she had caused his cattle to sicken and die.

Wenham initially denied being a witch, but a potion was found in her rooms, and she stumbled while reciting the Lord's Prayer, which people suggested was evidence of witchcraft.

But Wenham's witch trial became a cause célèbre in English society, and even the judge took a lenient view. When the prosecutors suggested that witnesses had seen Wenham flying, the judge remarked that flying was not illegal.

The trial eventually found Wenham guilty, but the judge set aside her conviction and suspended the death penalty. She died a free woman, in 1730.

Tom Metcalfe is a freelance journalist and regular Live Science contributor who is based in London in the United Kingdom. Tom writes mainly about science, space, archaeology, the Earth and the oceans. He has also written for the BBC, NBC News, National Geographic, Scientific American, Air & Space, and many others.