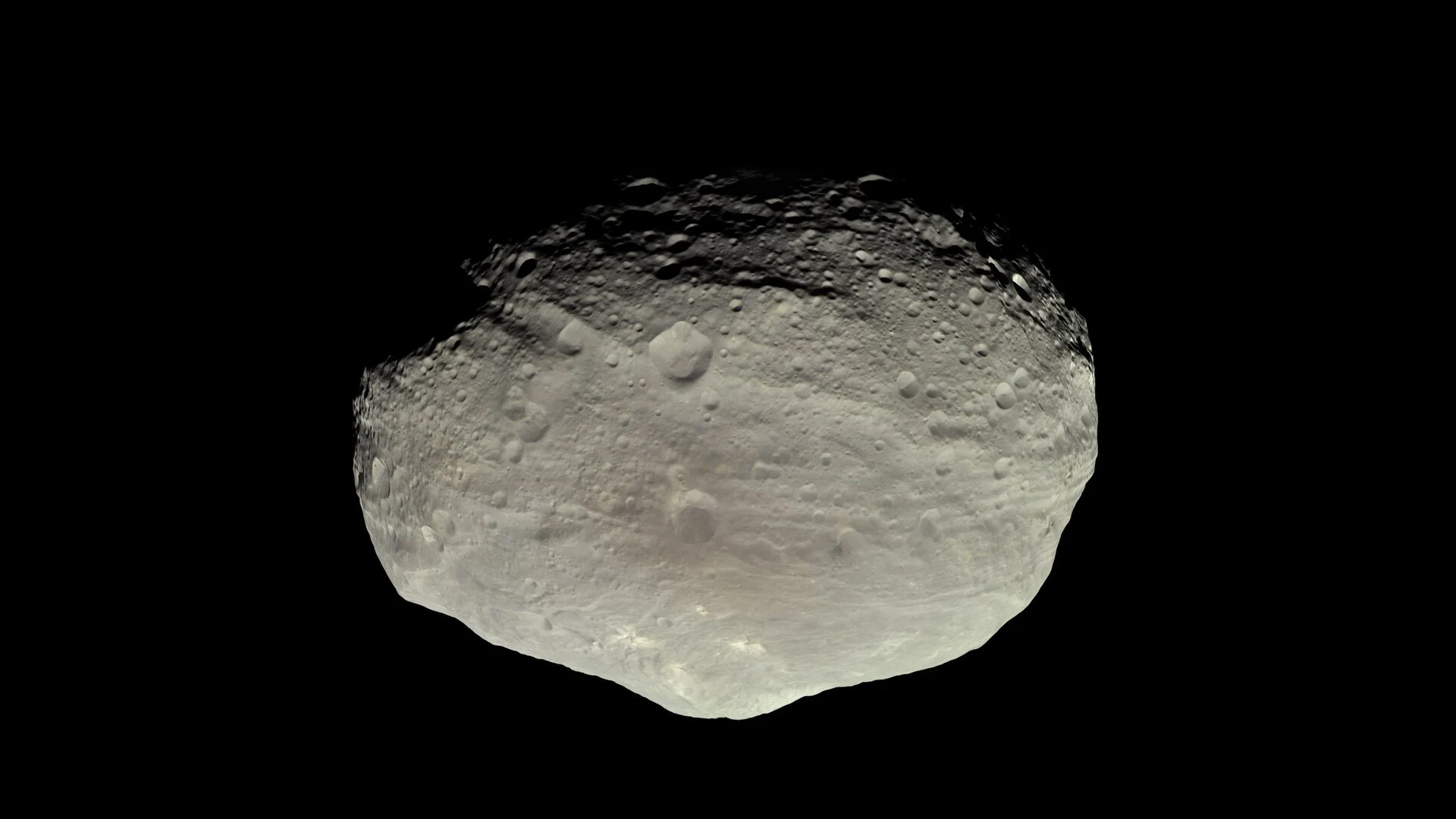

Huge Cache of Ancient Helium Discovered in Africa's Rift Valley

A "huge" cache of helium discovered in East Africa could ease a decades-long shortage of the rare and valuable gas.

Researchers in the United Kingdom and Norway say the newly discovered helium gas field, found in the East African Rift Valley region of Tanzania, has the potential to ease a critical global shortage of helium, a gas that is vital to many high-tech applications, such as the magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scanners used in many hospitals.

The researchers say the discovery is the result of a new approach to searching for helium that combines prospecting methods from the oil industry with scientific research that reveals the role of volcanic heat in the production of pockets of helium gas. [Elementary, My Dear: 8 Elements You Never Heard Of]

By one estimate, the newly discovered helium field in the geothermally active East African Rift Valley may contain more helium than the U.S. Federal Helium Reserve near Amarillo, Texas, which holds about 30 percent of the world's helium supply.

How much helium?

The Tanzania discovery was made by researchers from the University of Oxford and Durham University, both in the U.K., working with Helium One, a helium exploration company headquartered in Norway.

"We sampled helium gas (and nitrogen) just bubbling out of the ground in the Tanzanian East African Rift valley," Chris Ballentine, a geochemist in the Department of Earth Sciences at Oxford University, said in a statement. "By combining our understanding of helium geochemistry with seismic images of gas-trapping structures, independent experts have calculated a probable resource of 54 billion cubic feet [1.5 billion cubic meters] in just one part of the rift valley."

Meanwhile, the Federal Helium Reserve currently holds just 24.2 billion cubic feet, and the total known reserves in the U.S. contain about 153 billion cubic feet (4.3 billion cubic m), Ballentine said, while global consumption of helium is about 8 billion cubic feet (0.23 billion cubic m) per year.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The newly discovered gas field in Tanzania holds enough helium "to fill over 1.2 million medical MRI scanners," he said: "This is a game changer for the future security of society's helium needs, and similar finds in the future may not be far away."

One of the project leaders, geologist Jon Gluyas of Durham University, told Live Science that although the Tanzania gas field is large, it's only a small part of what the entire Rift Valley area may contain. "So it could be substantially larger," Gluyas said. "We will still have a lot of data to collect to be really confident, but yes — this is a globally significant discovery."

A new approach

Gluyas said the discovery hinged on a new understanding of the very complex and ancient nuclear, chemical and geological mechanisms that create helium in the Earth's crust and transport it into pockets that can be tapped by drilling.

"Almost more significant than the volume of helium found is that it was found on purpose," he said. "Every other discovery of helium to date has been found by accident."

Helium accumulates inside rock in the Earth's crust over billions of years, from the radioactive decay of the elements uranium and thorium. But the gas remains trapped in the rock until it is freed by very intense volcanic heat, such as that found in geothermally active regions such as the East African Rift Valley, Gluyas said.

By studying that process and the geological mechanisms that cause freed helium gas to accumulate in pockets, the researchers were able to identify potential drilling sites, he added.

Gluyas said the team took the same protocols and "applied the same sort of thinking you would for finding oil" to finding helium.

The fusion of hydrogen atoms produces large amounts of helium in the nuclear processes that power the sun. But here on Earth, helium is hard to find and hard to keep hold of, Gluyas said. Helium atoms are so small that the gas leaks out of almost every sort of container, and once helium escapes into the atmosphere, it's gone for good, he explained.

"In a bizarre sort of way, it is the ultimate nonrenewable element, and at the moment, it is not replaceable for many applications, certainly for medical systems such as MRI scanners," Gluyas said.

Scientific research associated with the discovery in Tanzania will be presented Tuesday (June 28) at the Goldschmidt Conference, which is being held in Yokohama, Japan, from June 26 to July 1.

Original article on Live Science.

Tom Metcalfe is a freelance journalist and regular Live Science contributor who is based in London in the United Kingdom. Tom writes mainly about science, space, archaeology, the Earth and the oceans. He has also written for the BBC, NBC News, National Geographic, Scientific American, Air & Space, and many others.