Images: How the Bird Beak Evolved

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Researchers led by Bhart-Anjan Bhullar, a paleontologist and developmental biologist at Yale University and developmental biologist Arhat Abzhanov at Harvard University reverted the beaks of chicken embryos into Velociraptor-like snouts. Here's a look at the chicken experiment and results. [Read the full story on the chicken embryos with dinosaur snouts]

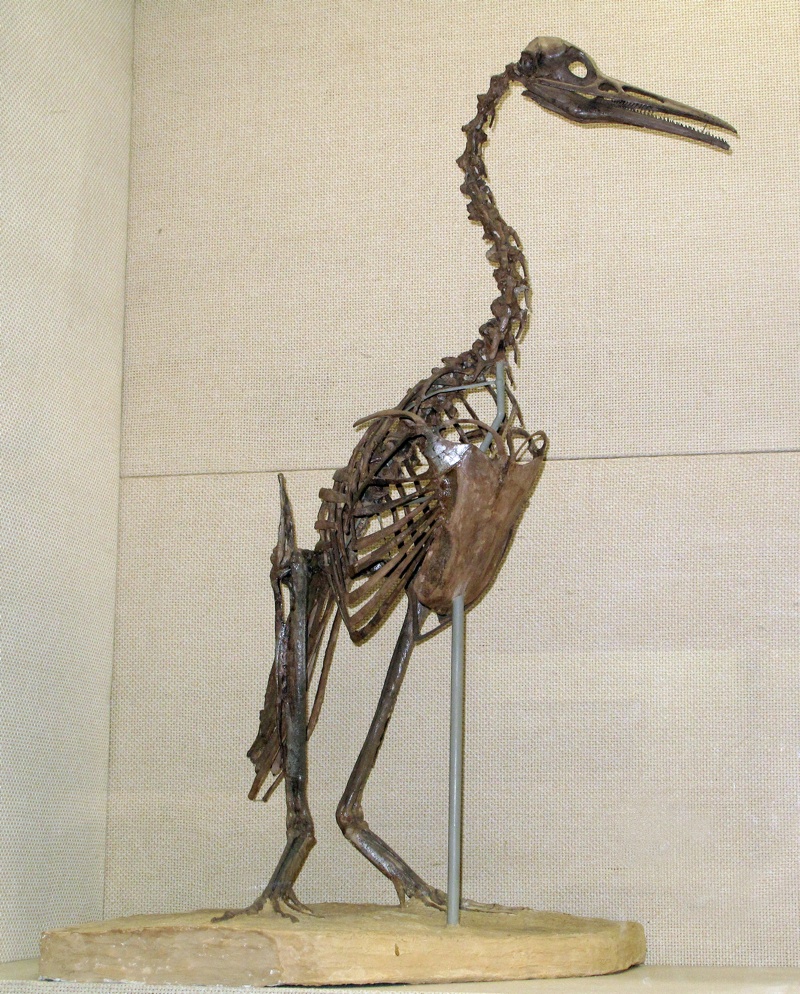

A modern beak

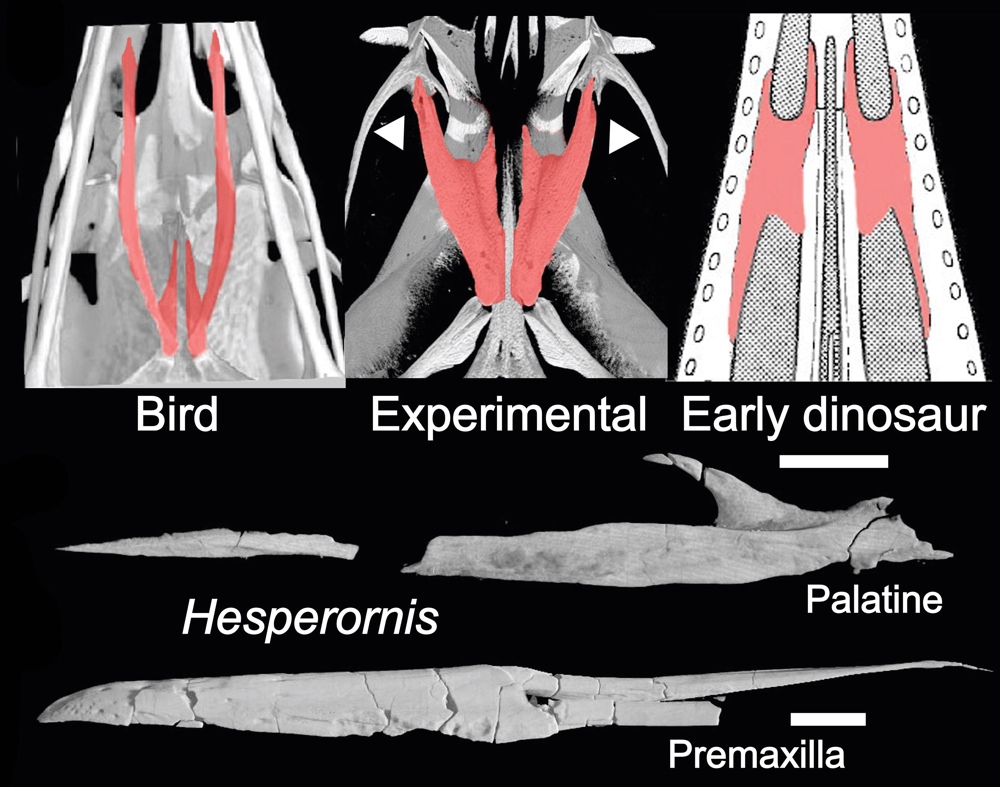

The dinosaur-nosed chicken embryos revealed that simple genetic tweaks might have led to the development of beaks in the ancestors of birds. In fact, such anatomic changes are seen in an extinct relative of modern birds — The 85-million-year-old Hesperornis bird (shown here) has the first-known modern beak and palate. Hesperornis was discovered by the great Yale paleontologist Othniel Charles Marsh in the middle of the 1800s. Credit: Copyright Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History.

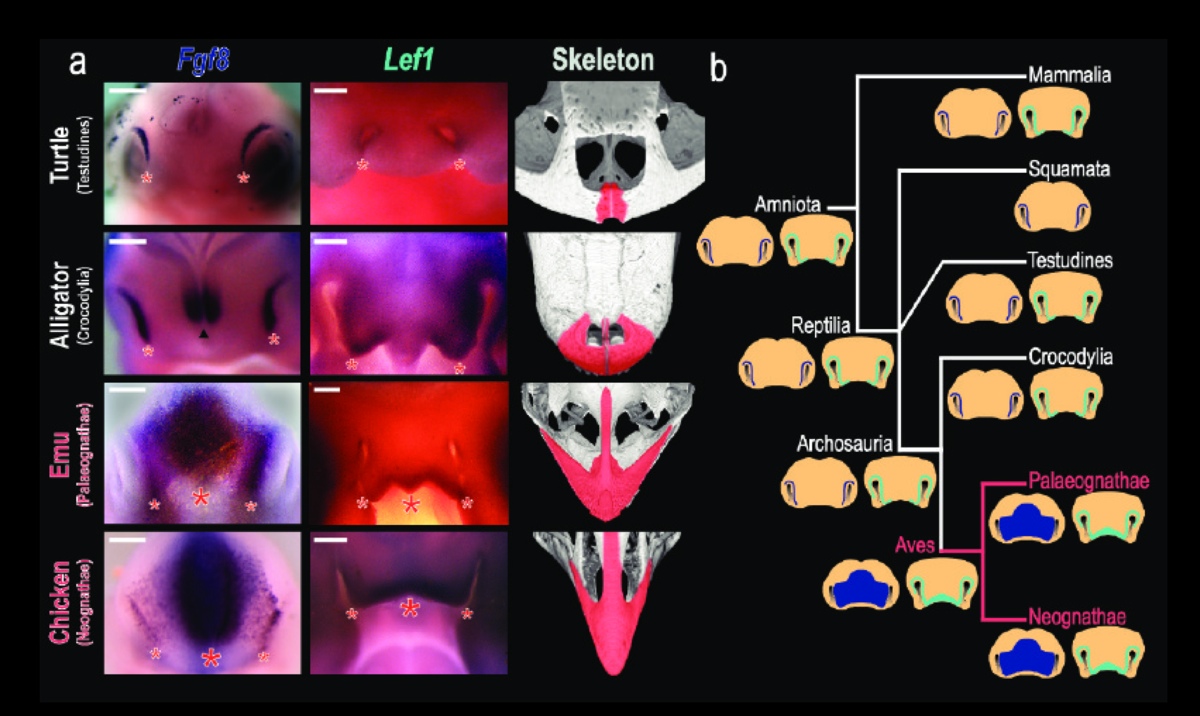

Early embryo faces

The researchers found that the bird beak formed from a pair of small bones called the premaxillae at the tip of the upper jaw. Unlike in other animals, the premaxillae are enlarged and fused in birds. Here, a look at these facial development genes, called Fgf8 and Lef1, in turtles, alligators and birds. The activity of these two genes differs between birds and reptiles early in embryonic development. Credit: Bhart-Anjan S. Bhullar, Arhat Abzhanov et al., journal Evolution

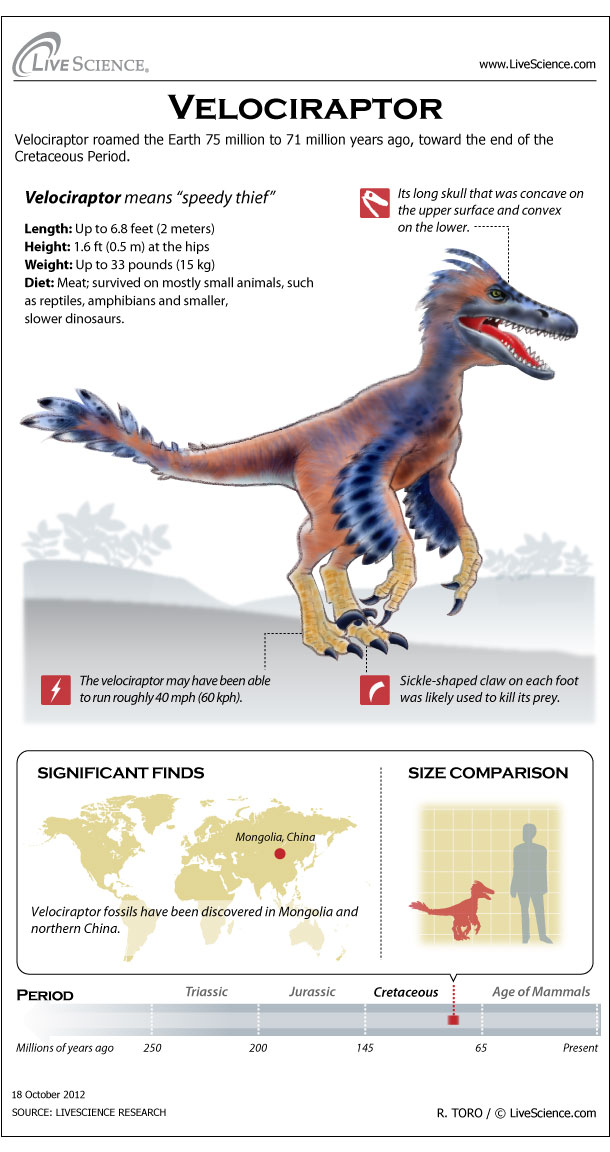

Velociraptor snout

The researchers found that the activity of the two facial development genes in birds differed from that of reptiles early in embryonic development right in the middle of their faces. They developed molecules that suppressed the activity of the proteins that these genes produced, which led to the embryos developing snouts that resembled their ancestral dinosaur state, more like Velociraptor (shown here) or Archaeopteryx.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

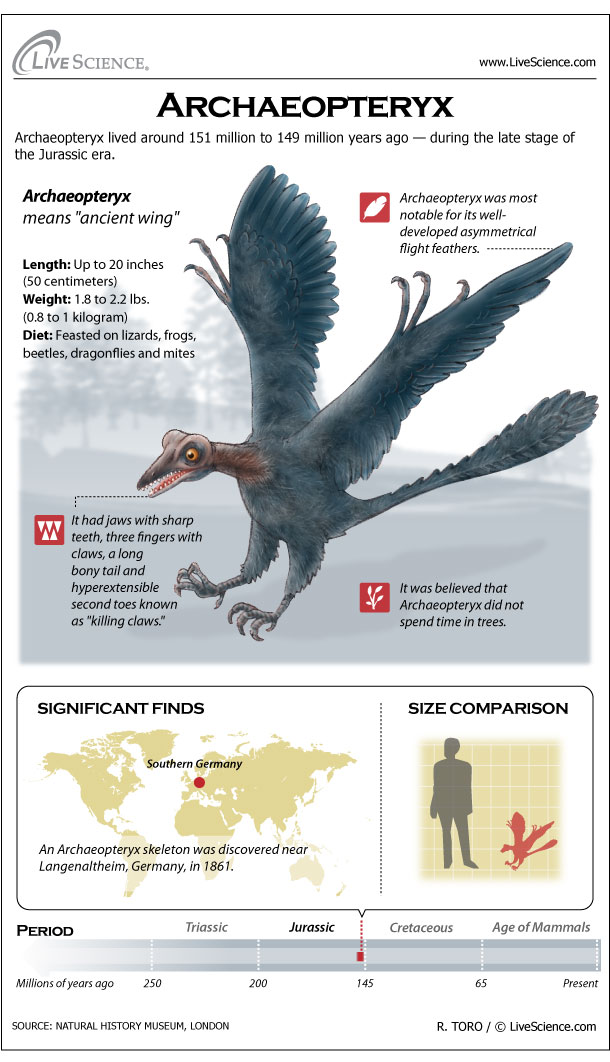

No teeth!

Even though the chicken embryos developed broad, rounded snouts rather than beaks, they still didn't have teeth (like Archaeopteryx, shown here, would have sported) and sported a horny covering on the nose, the researchers said.

Palatine bones

An artist rendition of the non-avian dinosaur Anchiornis (left) and a tinamou, a primitive modern bird (right), with snouts rendered transparent to show the premaxillary and palatine bones. Credit: John Conway.

Altered embryo

Here, CT scans of the palates of normal chickens, the "altered" embryo and a non-avian dinosaur showing the broad palatine bone (red). Below is the modern beak and palatine of the toothy bird Hesperornis. Credit: Bhart-Anjan S. Bhullar

Chicken skulls

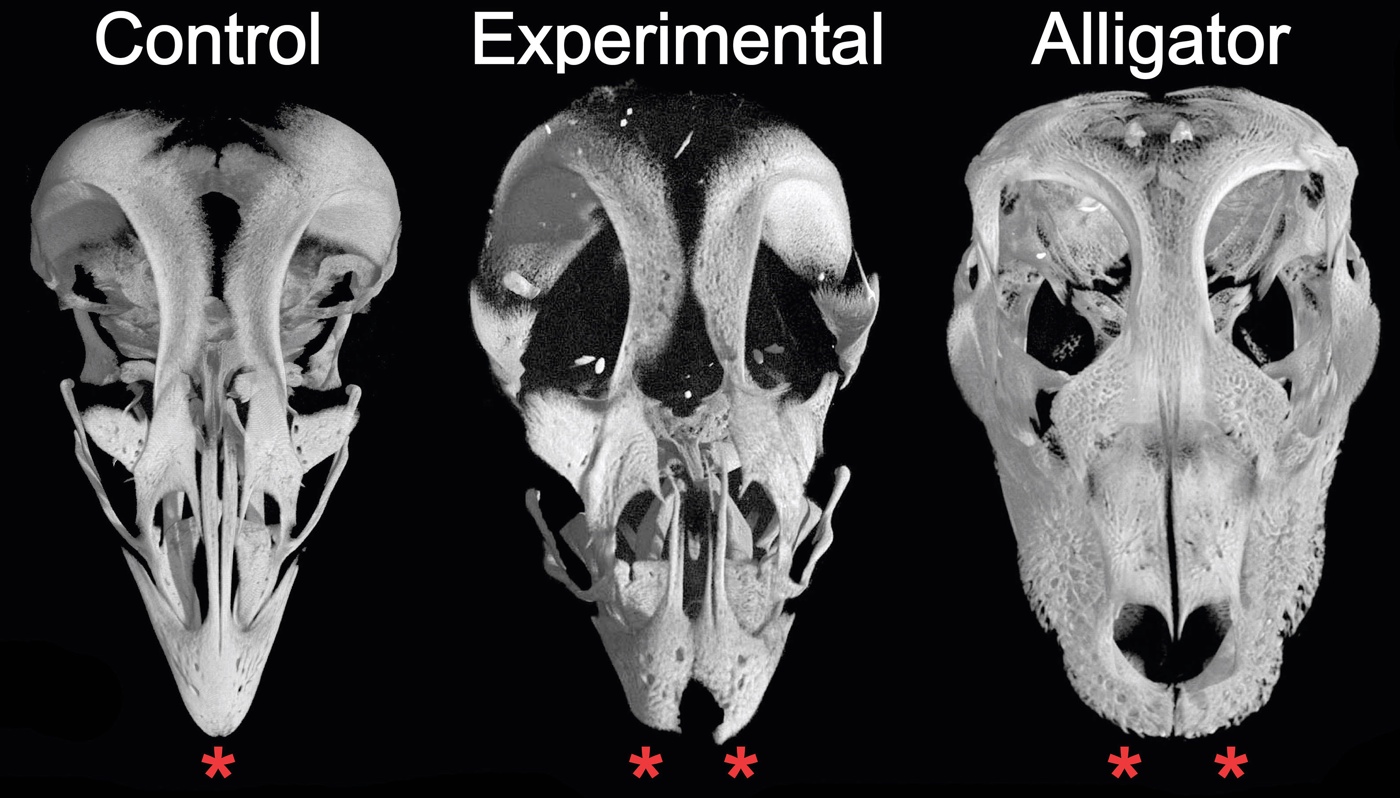

CT cans of the skulls of a control chicken embryo, altered chicken embryo and an alligator embryo. The chicken embryo whose protein activity had been modified shows the ancestral snout — or paired, short, rounded premaxillary bones. The shape of these bones and their lack of midline fusion make them more similar to those of alligators and of non-avian dinosaurs than of unaltered birds. Credit: Bhart-Anjan S. Bhullar

Jeanna Bryner is managing editor of Scientific American. Previously she was editor in chief of Live Science and, prior to that, an editor at Scholastic's Science World magazine. Bryner has an English degree from Salisbury University, a master's degree in biogeochemistry and environmental sciences from the University of Maryland and a graduate science journalism degree from New York University. She has worked as a biologist in Florida, where she monitored wetlands and did field surveys for endangered species, including the gorgeous Florida Scrub Jay. She also received an ocean sciences journalism fellowship from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. She is a firm believer that science is for everyone and that just about everything can be viewed through the lens of science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus