Ancient Receipt Proves Egyptian Taxes Were Worse Than Yours

Tax day is nearing in the United States, and people are scrambling to file their returns before the April 15 deadline. While this is never fun, people can take solace in a new finding: A recently translated ancient Egyptian tax receipt shows a bill that is (literally) heavier than any American taxpayer will pay this year — more than 220 lbs. (100 kilograms) of coins.

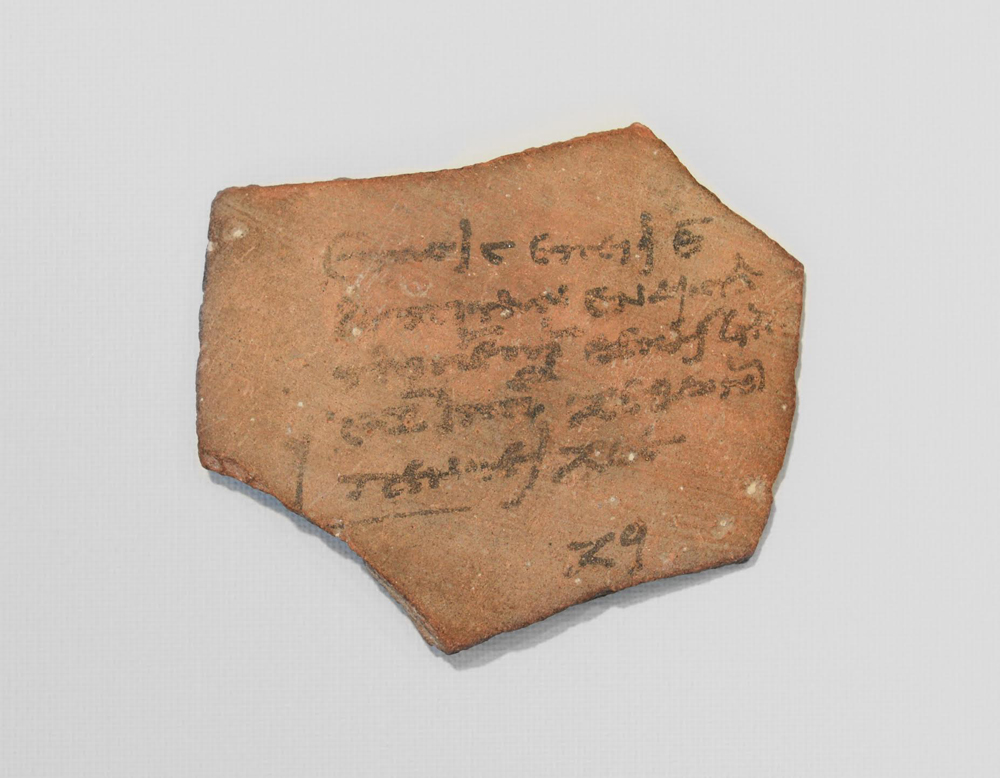

Written in Greek on a piece of pottery, the receipt states that a person (the name is unreadable) and his friends paid a land-transfer tax that came to 75 "talents" (a unit of currency), with a 15-talent charge added on. The tax was paid in coins and was delivered to a public bank in a city called Diospolis Magna (also known as Luxor or Thebes).

But just how much was 90 talents worth in ancient Egypt? [See photos of the ancient Egyptian tax receipt]

"It's an incredibly large sum of money," said Brice Jones, a Ph.D. student at Concordia University in Montreal, who translated the text. "These Egyptians were most likely very wealthy."

The receipt has a date on it that corresponds to July 22, 98 B.C. Paper money didn't exist at that time, and no coin was worth anywhere near one talent, the researchers said. Instead people made up the sum using coins that were worth varying amounts of drachma.

One talent equaled 6,000 drachma, so 90 talents totaled 540,000 drachma, researchers say. For comparison, an unskilled worker at that time would have made only about 18,000 drachmaa year said Catharine Lorber, an independent scholar who has published numerous journal articleson Egyptian coins.

In 98 B.C., the highest-denomination coin was probably worth only 40 drachms Lorber said. This made for a truly back-breaking tax load.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

It "would have taken 150 of these coins to make a talent, and 13,500 of them to equal 90 talents," Lorber told Live Science in an email. "The coins in question weigh, on average, 8 grams [0.3 ounces], so the total payment of 90 talents probably had a weight in excess of 100 kilograms [220 lbs.]."

What likely happened is that one or more tax farmers (people charged with collecting certain types of taxes) got 90 talents' worth of coins from the individuals paying this tax, the researchers said. These tax farmers then would have had to physically bring the cash into the bank. Lorber noted that the Ptolemies (the ruling dynasty in Egypt at the time) required tax farmers to absorb the cost of transport and handling. In cases where tax farmers had to bring in a big load, "it was packed in baskets and carried by donkeys," Lorber said. [6 Odd Historical Tax Facts]

The 15-talent surcharge, which was added on to the 75-talent tax bill, suggests that the people paying this land-transfer tax were penalized for not paying part of the bill in silver — a charge that was called the "allage," Lorber said.

"This was an exchange fee imposed on bronze currency when it was used to pay an obligation that legally should have been paid in silver," Lorber said. "This system was maintained even in periods when silver coinage was scarcely available."

Egyptian infighting

Today, people often complain about political gridlock and conflict on Capitol Hill, but this is likely nothing compared to the drama and infighting among Egypt's rulers around the time this newly translated bill was paid.

Around 98 B.C., Egypt's politics were volatile, to say the least. At the time, Egypt was ruled by Ptolemy X, a pharaoh who fought against his own brother for the throne. Some ancient writers even say he killed his own mother in 101 B.C. so he wouldn't have to share power with her.

Ptolemy X was part of a dynasty of pharaohs of Macedonian descent who ruled Egypt after the death of Alexander the Great.

Modern-day historians cast doubt on the ancient claim that Ptolemy X murdered his own mom, but in any event, he eventually lost power. In 89 B.C., his own army turned against him, and he was killed the following year. His brother Ptolemy IX then took over the country.

The ancient tax receipt is located at McGill University Library and Archives in Montreal. Jones is studying and translating several texts from the library and is set to publish his findings in an upcoming issue of the journal Bulletin of the American Society of Papyrologists.

Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Owen Jarus is a regular contributor to Live Science who writes about archaeology and humans' past. He has also written for The Independent (UK), The Canadian Press (CP) and The Associated Press (AP), among others. Owen has a bachelor of arts degree from the University of Toronto and a journalism degree from Ryerson University.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus