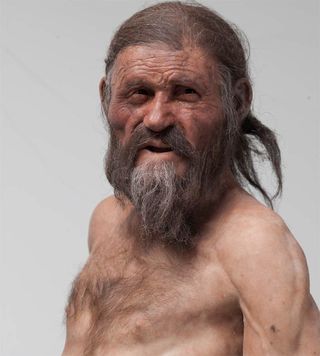

Ötzi the Iceman, a well-preserved mummy discovered in the Alps, may have had a genetic predisposition to heart disease, new research suggests.

The new finding may explain why the man — who lived 5,300 years ago, stayed active and certainly didn't smoke or wolf down processed food in front of the TV — nevertheless had hardened arteries when he was felled by an arrow and bled to death on an alpine glacier.

"We were very surprised that he had a very strong disposition for cardiovascular disease," said study co-author Albert Zink, a paleopathologist at the Institute for Mummies and the Iceman at the European Academy of Bozen/Bolzano in Italy. "We didn't expect that people who lived so long ago already had the genetic setup for getting such kinds of diseases."

Iceman scrutiny

Otzi was discovered in 1991, when two hikers stumbled upon the well-preserved mummy in the Ötztal Alps, near the border between Austria and Italy. Since then, every detail of the iceman has been scrutinized, from his last meal and moments (Ötzi was bashed on the head before being pierced by the deadly arrow blow), to where he grew up, to his fashion sense. [Top 9 Secrets About Ötzi the Iceman]

Past research has revealed that Ötzi likely suffered from joint pain, Lyme disease and tooth decay, and computed tomography (CT) scanning revealed calcium buildups, a sign of atherosclerosis, in his arteries.

Initially, the atherosclerosis was a bit of a surprise, because much research has linked heart disease to the couch-potato lifestyle and calorie-rich foods of the modern world, Zink said. But in recent research, as scientists conducted CT scans on mummies from the Aleutian Islands to ancient Egypt, they realized that heart disease and atherosclerosis were prevalent throughout antiquity, in people who had dramatically different diets and lifestyles, he said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"It really looks like the disease was already frequent in ancient times, so it's not a pure civilizational disease," Zink told Live Science.

Heart troubles

Scientists recently took a small sample of Ötzi's hipbone and sequenced the Neolithic agriculturalist's entire genome, to see where he fell on Europe's family tree. As part of that research, they found that the iceman had 19 living relatives in Europe.

In the new study, Zink and his colleagues found that Ötzi had several gene variants associated with cardiovascular disease, including one on the ninth chromosome that is strongly tied to heart troubles, the researchers reported today (July 30) in the journal Global Heart.

Despite spending years hiking in hilly terrain, it seems Ötzi couldn't walk off his genetic predisposition to heart disease.

"He didn't smoke; he was very active; he walked a lot; he was not obese," Zink said. "But nevertheless, he already developed some atherosclerosis."

The findings suggest that genetics play a stronger role in heart disease than previously thought, he said.

To follow up, the team would like to compare the genetic makeup of other mummies with the state of their arteries, to tease out just how much of a role genetics play in heart disease, Zink said. It would also be interesting to see whether ancient mummies exhibit signs of inflammation, the body's response to infection or damage, that has been tied to heart attacks, he added.

Follow Tia Ghose on Twitter and Google+. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Tia is the managing editor and was previously a senior writer for Live Science. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Wired.com and other outlets. She holds a master's degree in bioengineering from the University of Washington, a graduate certificate in science writing from UC Santa Cruz and a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin. Tia was part of a team at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that published the Empty Cradles series on preterm births, which won multiple awards, including the 2012 Casey Medal for Meritorious Journalism.

Most Popular