6 Children with Rare Disorders Helped by Gene Therapy

Two rare hereditary disorders, one of which kills children within the first few years of life, can be treated with gene therapy, new research from Italy suggests.

In children with the disorders, those who received gene therapy— in which a "faulty" gene is replaced with a healthy one — showed either improvement in their symptoms or a halt in the disease's progression. The children did not appear to experience serious side effects resulting from the gene therapy.

One disorder, called metachromatic leukodystrophy, causes a buildup of fatty acids in the brain, which leads to cognitive and movement problems and, ultimately, death at an early age.

The researchers treated three children with genetic mutations for metachromatic leukodystrophy, all of whom had older siblings with the condition. Because the patients were very young, ages 7 to 15 months at the study's start, they did not show full symptoms of the condition.

By age 3, one of the children treated with the gene therapy had a normal IQ score and language skills for his or her age, and was able to stand up voluntarily and walk holding someone's hand. In contrast, siblings of this patient who did not receive the therapy were incapable of speech and wheelchair bound by age 3.

The two other patients with the condition, who were also treated with gene therapy, did not show symptoms by age 2, an age at which researchers would have expected symptoms to appear.

Gene therapy was also used to treat three children with Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome, an immune system disorder caused by mutations in a gene called WAS. People with this condition are at increased risk for developing infections, as well as eczema. The children treated with the gene therapy saw their symptoms decrease or disappear within 20 to 30 months of undergoing treatment, the researchers said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Though the results are promising, the study period was relatively short, and researchers said they need to continue to monitor all six children for changes in their conditions. [9 Most Bizarre Medical Conditions ]

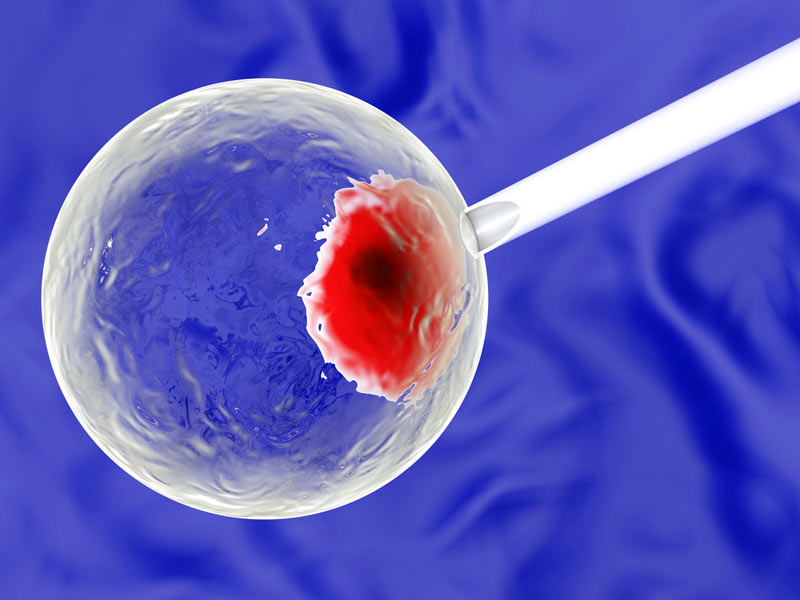

Both groups of children (those with metachromatic leukodystrophy, and those with Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome) received very similar gene-therapy treatments. The researchers removed blood stem cells, called hematopoietic stem cells, from the patients, and used a virus to introduce a corrected form of each patient's faulty gene. These cells were then infused back into the patients.

In patients with Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome, blood stem cells are directly affected by the disease, so the newly infused stem cells replace the diseased cells, the researchers said. For patients with metachromatic leukodystrophy, the newly infused stem cells find their way to the brain, where they release the corrected form of the gene product (a protein), which, in turn, is taken in by the brian cells.

Some earlier studies found that gene therapy can cause leukemia in some cases, because the new gene inserts in the wrong place and causes cells to turn cancerous. However, in the new research, there was no evidence that the treatment would increase the risk of leukemia.

The study, conducted by researchers at the San Raffaele Telethon Institute for Gene Therapy in Milan, Italy, is published today (July 11) in two papers in the journal Science.

Follow Rachael Rettner @RachaelRettner. Follow LiveScience @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.com.

Rachael is a Live Science contributor, and was a former channel editor and senior writer for Live Science between 2010 and 2022. She has a master's degree in journalism from New York University's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program. She also holds a B.S. in molecular biology and an M.S. in biology from the University of California, San Diego. Her work has appeared in Scienceline, The Washington Post and Scientific American.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus