Antarctic Meltdown Would Flood Washington, D.C.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Washington, D.C., and other coastal U.S. cities could find themselves under several more feet of water than previously predicted if warming temperatures destroy the West Antarctic Ice Sheet, a new study based on a model predicts.

The West Antarctic Ice Sheet (WAIS) towers about 6,000 feet (1,800 meters) above sea level over a large section of Antarctica. It holds about 500,000 cubic miles (2.2 million cubic kilometers) of ice, about the same amount of ice contained in the Greenland Ice Sheet.

This vast swath of ice is the anchor for numerous glaciers that drain into the polar sea and is bounded by the Ross and Ronne Ice Shelves. Whether or when this ice sheet might melt is still very uncertain, but even a partial melt would have a bigger impact on some coastal areas than others.

The new research found that sea level rise would not be uniform around the globe, owing to odd gravitational effects and predicted shifts in the planet's rotation.

Collapse concern

Throughout hundreds of millions of years in Earth's past, polar ice caps have grown and receded in cycles lasting thousands or even hundreds of thousands of years. When caps melted, seas rose.

What's different today is that melting of ice at both poles is occurring faster than what has naturally occurred in the past.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Some scientists are worried that our current path of warming could cause the collapse of all or part of the WAIS over the coming decades or centuries. These worries have been further fueled by a recent study in the journal Nature that indicates that more of the WAIS is warming than was previously thought.

"The West Antarctic is fringed by ice shelves, which act to stabilize the ice sheet — these shelves are sensitive to global warming, and if they break up, the ice sheet will have a lot less impediment to collapse," said co-author of the new study Jerry Mitrovica of the University of Toronto and the Canadian Institute for Advanced Research.

In its most recent report, released in 2007, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) estimates that a full collapse of the ice sheet would raise sea levels by 16 feet (5 meters) globally.

Mitrovica and his colleagues say that this is an oversimplification, and that sea level rise will be higher than expected, and greater in some places than in others.

In particular, the researchers say, the IPCC estimate ignores three important effects of such a massive ice melt:

- Gravity: Like planets and other cosmic bodies that exert a gravitational pull on each other, huge ice sheets exert a gravitational pull on the nearby ocean, drawing water toward it. If an ice sheet melted, that pull would be gone, and water would move away. In the case of the WAIS, the net effect would be a fall in sea level within about 1,200 miles (2,000 km) of the ice sheet and a higher-than-expected rise in sea levels in the Northern Hemisphere, further away.

- Rebound: The WAIS is called a marine-based ice sheet because the weight of all that ice has depressed the bedrock underneath to the point that most of it sits below sea level. If all, or even some, of that ice melts, the bedrock will rebound, pushing some of the water on top of it out into the ocean, further contributing to sea level rise.

- Earth's rotation: A collapse of the WAIS would also shift the South Pole location of the Earth's rotation axis (an imaginary line running through the Earth from pole to pole) —about 1,600 feet (500 meters) from its present location. This would shift water from the southern Atlantic and Pacific oceans northward toward North America and the southern Indian Ocean.

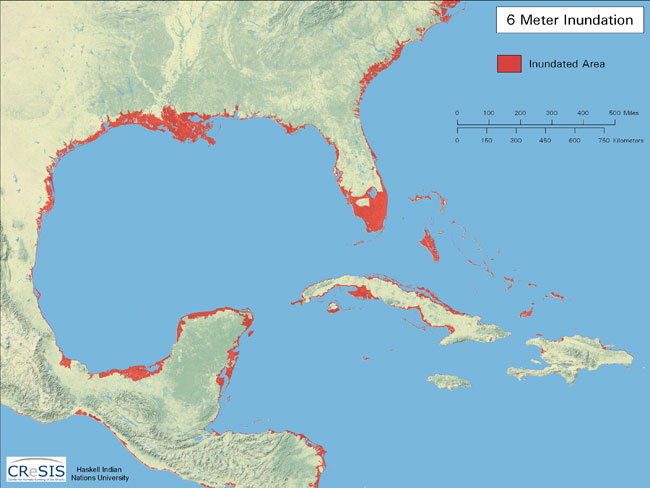

Mitrovica and his fellow researchers took these effects into account and came up with a new projection of what would happen across the world if the WAIS melted out. Their findings are detailed in the Feb. 6 issue of the journal Science. "The net effect of all of these processes is that if the West Antarctic Ice Sheet collapses, the rise in sea levels around many coastal regions will be as much as 25 percent more than expected, for a total of between 6 and 7 meters [20 to 23 feet] if the whole ice sheet melts," Mitrovica said. "That's a lot of additional water, particularly around such highly populated areas as Washington, D.C., New York City, and the California coastline." Submerging threat Six meters of sea level rise would eventually inundate the nation's capital, because even though it doesn't have an extensive coastline, it was originally a low-lying, swampy area connected to the Chesapeake Bay. It would also put virtually all of south Florida and southern Louisiana underwater. The West Coast of North America, Europe and coastal areas around the Indian Ocean would all be inundated more than previously expected. The impact of the additional sea level rise can be seen on this interactive map. "We aren't suggesting that a collapse of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet is imminent," said study co-author Peter Clark of Oregon State University. "But these findings do suggest that if you are planning for sea level rise, you had better plan a little higher." The study was funded by the Canadian Institute for Advanced Research, the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada, the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation and the U.S. National Science Foundation.

- Video – Learn How Ice Melts

- Antarctica News and Information

- Images: Ice of the Antarctic

Andrea Thompson is an associate editor at Scientific American, where she covers sustainability, energy and the environment. Prior to that, she was a senior writer covering climate science at Climate Central and a reporter and editor at Live Science, where she primarily covered Earth science and the environment. She holds a graduate degree in science health and environmental reporting from New York University, as well as a bachelor of science and and masters of science in atmospheric chemistry from the Georgia Institute of Technology.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus