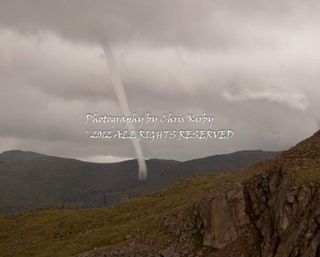

Rare Colorado Tornado Second-Highest in US History

Most of the time, Chris Kirby chases storms, but sometimes they come to him. During a drive through the mountains this Saturday afternoon (July 28) near his home in Aurora, Colo., to photograph mountain goats and test radio equipment, he got quite a surprise: a rare, high-elevation tornado.

Kirby, who's a registered storm-spotter with the National Weather Service (NWS), took a photo of the thin twister as it briefly touched down on the side of Mount Evans, he told OurAmazingPlanet. He sent his picture to weather service staff, who used maps and line-of-sight analysis to determine that the twister touched down at 11,900 feet (3,627 meters), making it the second-highest tornado ever recorded in American history, said David Barjenbruch, a meteorologist with the NWS in Boulder.

"The funnel briefly touched down on a ridge, just enough to be deemed a tornado," Kirby said. "I'm blessed to have seen such an extremely rare phenomenon."

The highest twister ever recorded was photographed by a hiker at 12,000 feet (3,658 m) in California's Sequoia National Park on July 7, 2004, Barjenbruch told OurAmazingPlanet.

Uncommon tornado

Tornadoes aren't commonly recorded high in the mountains in part because fewer people — and fewer weather-spotters — live in these regions and they are more difficult to traverse, Barjenbruch said.

More importantly, mountains break up the large-scale weather systems that give rise to most tornadoes. Areas with high elevation have less atmospheric instability, a key ingredient in tornado formation, Barjenbruch said. Instability is marked by a large temperature difference between warm, moist air near the ground and colder air higher up, which gives rise to thunderstorms and tornadoes. [Infographic: Tornado! How, When & Where Twisters Form]

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

This twister was a non-supercell tornado, also known as a "land spout," Barjenbruch said. Supercell tornadoes are common in the Midwest and South in spring and summer and are formed by thunderstorms that result when large masses of warm, moist air encounter colder air higher up. The lack of Gulf of Mexico moisture in the Rocky Mountains for most of the year and mountainous terrain makes these types of tornadoes a rarity, he said.

The tornado was an EF-0 and didn't cause any damage. "It was a small narrow funnel, but a very picturesque funnel," Barjenbruch said.

It was generated by an updraft of air, pushed into the mountains by thunderstorms moving through the area, interacting with wind shear set up by the mountains, resulting in a swirling funnel made visible by water vapor, Barjenbruch said. These types of tornadoes are rare and usually not very powerful, he said.

On July 21, 1987, there was an EF-4 tornado in Wyoming between 8,500 and 10,000 feet in elevation, the highest altitude ever recorded for a violent tornado, according to the NWS.

Where are all the tornadoes?

According to preliminary data from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, there have only been 24 tornadoes reported throughout the United States in July, which is by far the fewest for the month since recordkeeping began in the early 1950s. If the twisters stay at bay, this month will shatter the old record of 42 tornadoes set in July 1960.

What's causing the dearth of twisters? "The one-word answer is drought," said Bob Henson, a meteorologist and science writer for the National Center for Atmospheric Research in Boulder, Colo. Fewer rainstorms means fewer chances for tornadoes, which only form in thunderstorms. "If you don't have thunderstorms, you can't get a tornado," Henson told OurAmazingPlanet earlier this month.

Record drought has gripped much of the country, with nearly two-thirds of the lower 48 states in moderate to exceptional drought. Part of the reason for the drought — and hence the lack of tornado-producing storms — is the presence of a high-pressure "heat dome" over much of the country.

Reach Douglas Main at dmain@techmedianetwork.com. Follow him on Twitter @Douglas_Main. Follow OurAmazingPlanet on Twitter @OAPlanet. We're also on Facebook and Google+.

Most Popular