Trekking to a Treacherous Glacier

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Melting Mountain

To find clues about the Earth's past climate, sometimes you have to get extreme. That's why scientists recently traveled to Indonesia's Puncak Jaya, the Earth's highest island peak and the tallest mountain between the Andes and the Himalayas. It's here that the last glaciers in the tropical Pacific are found.

Scientists scaled the 16,000-foot- (4,884-meter-) tall mountain which is about as tall as 11 Empire State Buildings and sank their drills into the rapidly dwindling glaciers to remove frozen tubes of ice, called ice cores. The team was on the ice from June 11 to June 28.

Ice cores are like climate time capsules buried thousands of years ago that show successive layers of ice and snow that have been laid down on glaciers. They enclose tiny bubbles that contain samples of the atmosphere trapped when each layer of ice first formed. By unlocking their secrets, scientists will reveal how the climate has changed over thousands of years.

Saddle Up

Saddle camp the U-shaped area on top of Puncak Jaya was the scientists' evening home after a long day of drilling during their mission. Here, the researchers lived in tents scattered around deep crevasses in the ice. At the camp, researchers squawked on handheld radios and helicopters buzzed overhead.

It's now-or-never to study these glaciers, according to the scientists. The glaciers around Puncak Jaya lost nearly 80 percent of their area between 1936 and 2006 two-thirds of that loss has come since 1970. Satellite images show a 7.5 percent drop between 2002 and 2006.

The ice melt is obvious atop the mountain. Upon arriving, the researchers spotted a lake on top of a glacier a bad sign for the ice. The lake could trap heat and eat away at the rest of the already thin glacier. Today, the ice is maybe 100 feet (30 m) thick, said expedition leader and paleoclimatologist Lonnie Thompson of Ohio State University.

Start Your Engines

After a brief period of panic (the team's ice drills were lost thanks to a shipping mix-up and had to be fetched from a warehouse that was a 5-hour flight away), the ice harvesting began. The team drilled at three sites on the Northwall Firn Glacier and removed two cores at each site. At the first drill site, the researchers drilled until hitting bedrock about 100 feet (30 m) under the surface of the ice.

Just because the researchers are drilling straight down into the ice doesn't mean that analyzing the ice is straightforward. Before boring into the ice, scientists studied how parts of the glacier have cracked and shifted over the years. Places where the ice is cracking, called faults, are common on alpine glaciers. At these faults, some parts of the ice slide under or over others, so scientists can't assume that the youngest ice is toward the top of the glacier. This means that an ice core doesn't read like a climate timeline. Rather the cores require a more complicated analysis that is becoming more difficult by the day as the ice melts.

Careful

Dense fog had clouded the already treacherous drill site by mid-morning on one day during the mission. Regular mid-afternoon lightening cut short the drilling days. As a safety precaution, the drill site was evacuated by 2 p.m. local time (1 a.m. ET) every day.

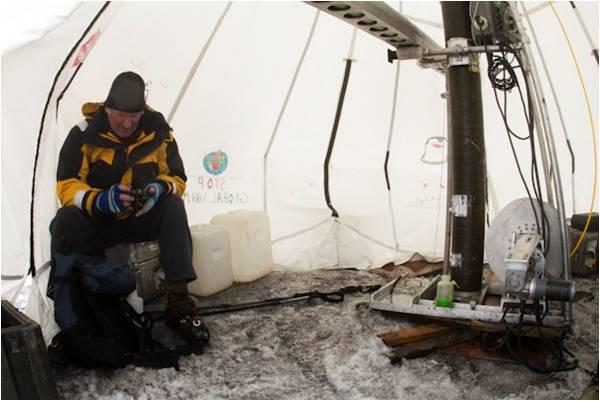

Manning the Drill

The drills ran on generators that powered what's known as a hollow-bit tip. This drill bit was trailed by a long pipe that let the scientists pull up the ice cores as the bit penetrated the glacier.

Once the cores were harvested, they were immediately placed inside portable freezers. These freezers were also powered by generators and kept the ice cores frozen until a load could be moved off the mountain. The cores were then taken to the large freezer in the nearby city of Tembagapura the first stop on the long trip back to Ohio.

Ice Cores

After the drilling came the hard part: Moving the cores from the glacier before they melted. On June 13, an ice core stretching 75 feet (23 m) from the first drill site arrived in Tembagapura. The core was then loaded into insulated ice core boxes that were stuffed with frozen cold packs.

The ice was wrapped in plastic bags with important data about the cores noted on the outside. Life-Support Helicopters were essential for the project. Aside from supplying the camp with medical supplies and life-support, the helicopters were required to quickly move the cores from the mountain. Freezers were placed in a sling load and flown down the glacier. There was no time to spare. If the cores melted on the way back to Ohio, the entire trip would have been wasted.

Melting Mountain

The ice cores are now in transit from Indonesia to Ohio, where researchers will spend months piecing together the climate history of Puncak Jaya. Some predictions, however, won't take months. From their observations at saddle camp, the researchers said the glacier is on pace to lose several feet of ice every year.

Once the glacier melts, the climate data stored within it will be gone. Puncak Jaya is the only place to get ice core data from the western side of what's known as the Pacific Warm Pool the single largest heat source to the global atmosphere. The researchers got ice cores from the opposite side of the tropical Pacific Ocean at Nevado Haulcan, Peru, in 2009. Together, the cores will help scientists understand how shifting weather patterns can alter the Earth's climate.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus