Mouth of Giant Black Hole Measured for First Time

For the first time, scientists have peered to the edge of a colossal black hole and measured the point of no return for matter.

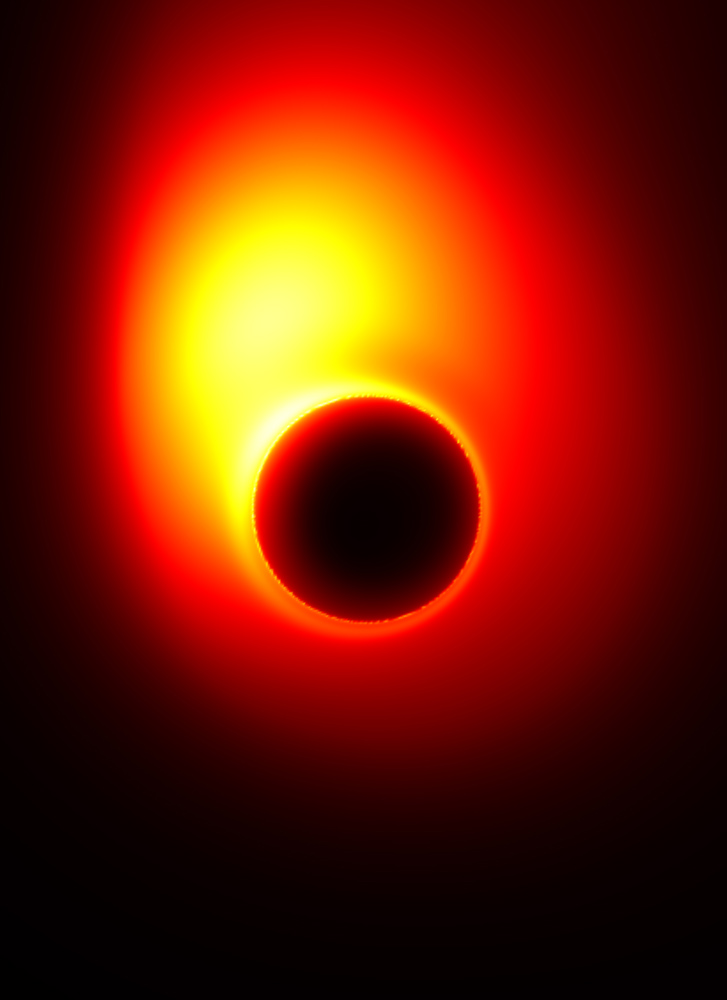

A black hole has a boundary called an event horizon. Anything that falls within a black hole's event horizon — be it stars, gas, or even light — can never escape.

"Once objects fall through the event horizon, they're lost forever," Shep Doeleman, assistant director of the MIT Haystack Observatory and research associate at the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory, said in a statement Thursday (Sept. 27). "It's an exit door from our universe. You walk through that door, you’re not coming back."

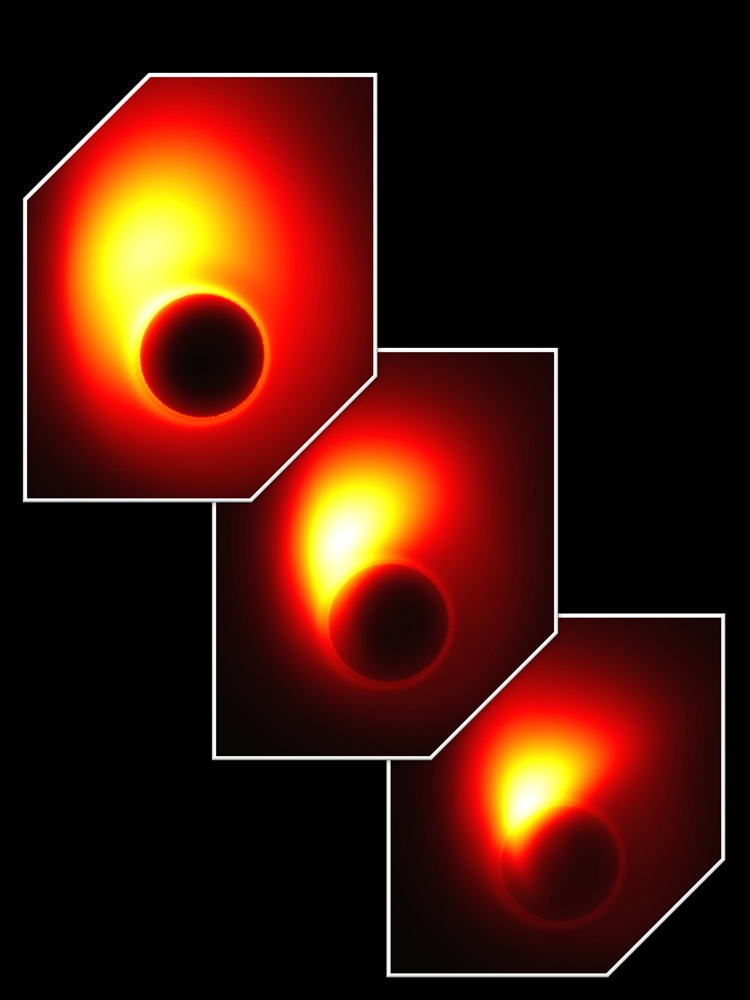

Although the event horizon is an imaginary line that's impossible to observe, astronomers have imaged the region around a giant black hole at the center of a distant galaxy, and measured, for the first time, the closest stable orbit in which matter can circle the black hole. The findings were reported today in the journal Science.

The supermassive black hole in question lies at the center of the galaxy M87, which is about 50 million light-years from our own Milky Way. This behemoth black hole contains the mass of 6 billion suns.

Using a new observatory called the Event Horizon Telescope, which links up radio dishes in Hawaii, Arizona and California, astronomers measured that the innermost possible orbit for matter around the black hole is roughly 5.5 times the size of the black hole's event horizon.

This innermost orbit is about five times the size of the solar system, or 750 times the distance from Earth to the sun, Doeleman told SPACE.com. The distance between the Earth and the sun is nearly 93 million miles (150 million kilometers).

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The observations allowed the researchers to confirm that this swirling mass around the black hole is the source of the powerful jets of light seen radiating from the galaxy. Many galaxies throughout the universe spot similar jets, thought to be produced by matter falling into their central black holes. Until now, no telescope has had the resolution power to verify the idea.

The Event Horizon Telescope is a new project that aims to link as many as 50 radio dishes around the world to work in concert to image the distant universe. Already, the observatory can see celestial objects with 2,000 times more detail than the Hubble Space Telescope.

This story was provided by SPACE.com, a sister site to LiveScience. You can follow SPACE.com on Twitter @Spacedotcom. We're also on Facebook & Google+.