Seafloor "Bridges" Found to Span Earth's Deepest Trench

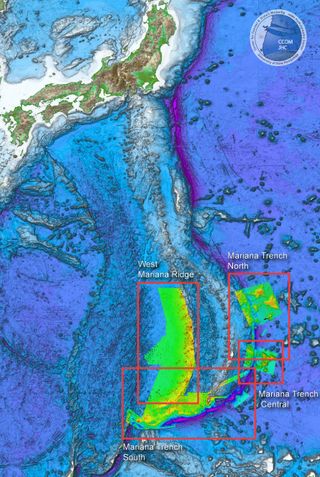

The Mariana Trench, located in the Pacific Ocean off the eastern coasts of Japan and the Philippines — at a depth of around 6.8 miles (11 kilometers) below sea level — is famous for being the deepest point on the planet's surface.

Now, to add to the Mariana Trench's fame, marine geophysicists recently mapped a set of surprising seafloor features nearby. At least four underwater "bridges" span the depths of the trench, where the Pacific Plate dives under the Philippine Plate.

"It wasn't common knowledge that these bridges occurred at all," said James Gardner, a marine geophysicist at the University of New Hampshire who found the structures. "This is really the first time they've been mapped in any detail."

Bridging the trench

As the Pacific and Philippine tectonic plates converge, they carry seamounts (mountains on the ocean floor that don't reach the water's surface) and other underwater features with them toward the trench itself. Some of these plow into other structures on the opposite side of the trench — in a sort of slow-motion seamount collision — or into the trench wall itself.

The result is an underwater "bridge" that stretches across the Mariana Trench. Gardner and a colleague found four of these structures, some rising as high as 6,600 feet (2,000 meters) above the trench and measuring up to 47 miles (75 km) long.

The largest of the four, Dutton Ridge, was mapped in low resolution in the 1980s, but scientists hadn't noticed any other similar structures in the area. Because the seafloor in the region is riddled with seamounts, guyots (flat-topped seamounts) and other features — many of them part of the Magellan Seamount chain — Gardner suspected he could find other bridges.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"As the Pacific Plate gets thrust down underneath the Philippine Plate, it wouldn't be totally unexpected that you'd find these things bridging across the trench and being accreted to the inner wall," Gardner told OurAmazingPlanet.

Using a multibeam echosounder (a tool that uses sonar to measure the topography of the ocean floor in detail), Gardner and a colleague mapped a large swath of the ocean floor surrounding the trench. They presented their findings at the December meeting of the American Geophysical Union in San Francisco.

Deep, cold and creeping slowly

What the bridges mean for the ocean floor and its occupants is unclear, Gardner said.

"I would certainly expect Dutton Ridge and the others to have different fauna and flora than the trench floor, because they stand about 2 kilometers [1.2 miles] higher,” Gardner said. "But the extreme depth would make it hard to monitor the biology or seafloor currents in the area."

In fact, the pressure at the bottom of the Mariana Trench is more than eight tons per square inch, and water temperatures hover just above freezing, making it a challenging environment for researchers and sea life alike.

The long-term fate of the bridges is also unknown, Gardner said.

Dutton Ridge, the northernmost of the four bridges, has settled in over the Mariana Trench and seems to be "choking" the plate boundary for now, Gardner said. He also found evidence suggesting that the trench may have already swallowed up other similar bridges.

Whether and when Dutton Ridge and the other three bridges will plunge to the same end isn't clear. And with the Pacific and Philippine plates creeping steadily toward each other at a rate of less than an inch (2 cm) per year, we aren't likely to find out anytime soon.

This story was provided by OurAmazingPlanet, a sister site to LiveScience.

Most Popular