Beasts in Battle: 15 Amazing Animal Recruits in War

Introduction

Humans have enlisted animals to help fight their wars since prehistoric times, and some of the world’s earliest historical sources tell of battles between ancient warlords in horse-drawn chariots. Dogs and horses were probably the first animals used in war, and many are still used today in modern military and police tasks.

But, an even wider range of creatures have been used to fight human battles throughout history. Here we count down some of the unwitting animals that have been recruited to fight in both ancient and modern warfare.

Related: What Really Happens to Fighting Bulls After the Fight?

Pigeons

Pigeons have been used to carry messages since at least the 6th century B.C., when the Persian king Cyrus is said to have used pigeons to communicate with the distant parts of his empire. Like many species of birds, pigeons have an innate homing ability that is thought to be based on their sensitivity to the direction of the Earth's magnetic field. Some specially bred homing pigeons have found their way home from more than 1,800 miles (2,900 km) away.

Because of this ability, pigeons have been used to carry messages for conquerors and generals throughout much of human history. But, their homing superpower only works one way: usually the birds need to be transported to where they will be used, to fly back home with a message.

During the four-month Siege of Paris by Prussian forces in 1870 and 1871, Parisians trapped inside the city used messenger pigeons to communicate with their compatriots outside. The French military used hot air balloons to send hundreds of caged homing pigeons over the enemy lines, where they could be collected and used to send microfilm messages back into the city. The use of messenger pigeons reached its peak in World War I, just before the widespread adoption of radio, when more than 200,000 messenger pigeons were used by Allied forces alone.

One of the most famous wartime pigeons, named Cher Ami, earned the French "Croix de Guerre" for delivering 12 messages between forts in the Verdun region of northern France. The plucky bird made his last message delivery despite having suffered serious bullet injuries, and is credited with saving the "Lost Battalion" of the U.S. 77th Infantry Division, which had become cut off by German forces.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Another group of 32 pigeons earned the British Dickin medal for animal valor during the D-Day invasion of World War II, when Allied soldiers kept radio silence and relied on the pigeons to relay messages.

Bears

Bears appear a few times in the history of warfare, but one bear in particular became famous for his exploits against the Germans during World War II.

Voytek was a Syrian brown bear cub adopted by troops from a Polish supply company who purchased him while they were stationed in Iran. The bear grew up drinking condensed milk from a vodka bottle and drinking beer. When the Polish troops were moved around as the war progressed, Voytek went too: to battle zones in Iraq, Palestine, Egypt and then Italy.

Soon, Voytek had grown to weigh more than 880 pounds (400 kg) and stood more than 6 feet (1.8 meters) tall. In time, he was enlisted as a private soldier in the supply company, with his own paybook, rank and serial number, and eventually rose to the rank of corporal in the Polish Army. In 1944, Voytek was sent with his unit to Monte Casino in Italy, during one of bloodiest series of battles of World War II, where he helped carry crates of ammunition.

In his later years, Voytek lived at the Edinburgh Zoo in Scotland, where he’d been stationed with his adopted supply company at the end of the war. He became a popular public figure in the United Kingdom, and often appeared on children’s television shows until his death in 1963.

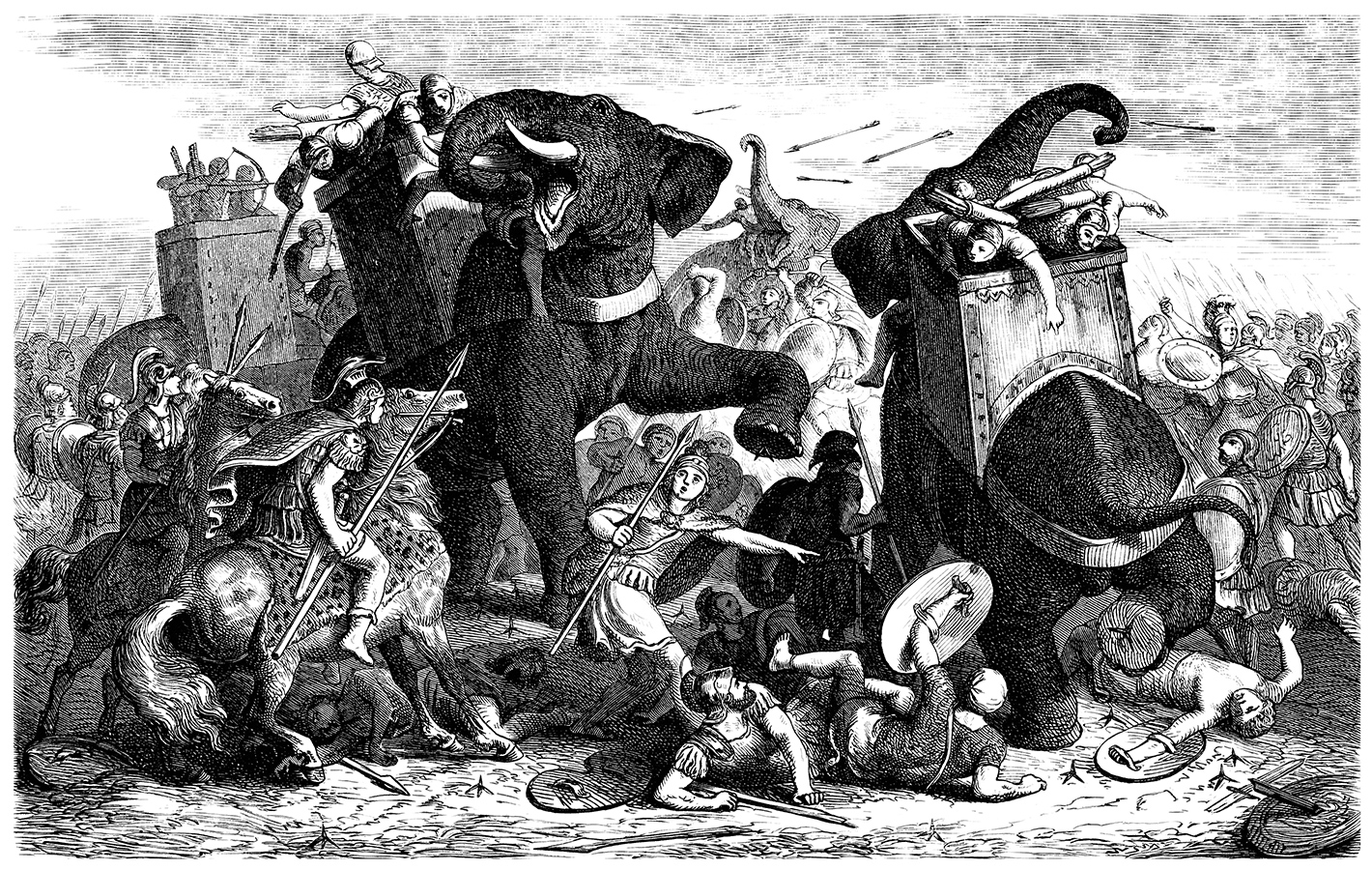

Elephants

Elephants, the largest land mammals on Earth, made their mark in ancient warfare as creatures capable of devastating packed formations of enemy troops. Elephants could trample enemy soldiers, gore them with their tusks and even throw them with their trunks. They were often armored against enemy weapons, or had their tusks tipped with iron spikes. Some even carried a raised fighting platform on their backs for archers and javelin throwers.

Elephants were first used in war in India around the 4th century B.C., many centuries after wild Asian elephants first began to be tamed there around 4500 B.C. Elephants breed slowly and the captive herds were small, so wild males were usually caught and trained to be war elephants. In 331 B.C., the invading armies of Alexander the Great encountered the war elephants of the Persian Empire for the first time at the Battle of Gaugamela. The elephants terrified Alexander’s soldiers, but that didn’t stop them from winning the battle, and soon Alexander added all of Persia's war elephants to his own forces.

In 280 B.C., the king Pyrrhus of Epirus borrowed more than 20 African war elephants from the Egyptian king Ptolemy II, to attack the armies of the Roman Republic at the Battle of Heraclea in southern Italy. The elephants helped to rout the Romans, but by the time of the battle of Asculum the next year, the Romans had developed anti-elephant wagons covered in iron spikes and troopers were specially trained to attack the elephants with javelins. Pyrrhus also won that battle against Rome, but with huge losses among his troops, giving rise to the term "a Phyrric victory." The Romans also faced elephants in the Punic wars against Carthage, and in the Second Punic War (201-218 B.C.), the Carthaginian general Hannibal Barca led war elephants over the Alps to attack Italy from the north. Many animals died during the crossing.

Later, the Romans used war elephants themselves in their conquests in Spain and Gaul, where they were known for their terrifying psychological effect on undisciplined "barbarians." War elephants were also used in the Roman invasion of Britain under the Emperor Claudius in 43 A.D. Ultimately, elephants proved unsuited to war — they were too vulnerable to massed weapons, and too likely to panic: the terrified giant beasts often caused as much damage to their own forces as they did to the enemy.

Elephants continued to be used as war animals in Asia and India until recent centuries, and some animals continue today in ceremonial military roles, but the emerging use of cannons eventually ended their role in combat.

Camels

Camels still serve as military patrol mounts in the deserts, mountains and wastelands of several regions of the world. Although a camel cannot charge as fast as a horse, they are valued for their ability to endure long marches in harsh and sometimes almost waterless conditions.

Archaeologists think camels were first tamed as pack animals and as herd animals for milk and meat in North Africa and the Middle East around 3,000 years ago. The first recorded use of camels in war is in 853 B.C., when the Arab king Gindibu fielded 1,000 camels in an allied army united against the Assyrians at the Battle of Qarqar, in modern-day Syria. In later centuries, the Parthian and Sassanid Persians sometimes armored their camels entirely, like cataphract heavy horse cavalry.

From the 7th century A.D., Arab, Berber and Moorish camel troops were an important part of the Muslim armies that conquered the Middle East, North Africa, and southern Spain. Foreign camel troops were often employed in the European colonial armies of the 18th and 19th centuries, in the Middle East, Africa and India. Several countries still maintain units of camel cavalry descended from those colonial forces.

In World War I, both the Ottoman and Allied forces in the Middle East included camel cavalry among their forces. Camels were also used in the Arab rebellion against Ottoman rule in the Hejaz region of the Arabian Peninsula, with the aid of the British Army officer T.E. Lawrence, known as "Lawrence of Arabia."

Dogs

Dogs may be man's best friends, but they can also be fearsome opponents. The first dogs of war were probably hunting dogs that joined their masters in raids on hostile human communities. Since then, large dog breeds have served on battlefields, as scouts and as defensive sentries for everyone from the ancient Egyptians to Native American peoples.

One of the earliest accounts of dogs fighting in battle comes from the early kingdom of Lydia in Asia Minor around 600 B.C., where a pack of Lydian war dogs routed and killed a number of invaders.

The Roman legions bred their own war dogs from an ancient mastiff-like breed known as the Molloser. They were mainly used as watchdogs or for scouting, but some were equipped with spiked collars and armor, and were trained to fight in formation.

Today's dogs of war are mainly limited to the battlefield roles of messengers, trackers, scouts, and sentries alongside human handlers. They are also used in military policing tasks, such as the U.S. military’s bomb-sniffing dogs in Afghanistan and Iraq.

Horses

No other animal has played so great a role in the history of warfare as the horse. Archaeologists have found evidence of the use of horses by raiding nomads as early as 5,000 years ago on the steppes of central Asia and eastern Europe, where it is thought horses were first domesticated.

Several "kurgan" burial mounds across an area from Ukraine to Kazakhstan, some dated to as early as 3000 B.C., hold the remains of horses that were sacrificed at the death of their nomad rider and buried alongside him, along with bridles, saddles, and weapons. Later burial mounds from the same region, dated to around 2000 B.C., hold the earliest horse-drawn chariots.

The use of horses in war is also documented in ancient historical documents, including the War Panel of the Standard of Ur, from the Mesopotamian city of Sumer in around 2500 B.C., which shows horses or donkeys pulling a four-wheeled wagon. From around 1600 B.C., the powerful Hittite civilization in Anatolia were famed for their use of horse-drawn war chariots as a stable platform for fighting with bows and spears. And in the centuries that followed, chariots were in use from ancient Egypt to ancient China.

One of the world’s earliest war stories, Homer’s "Iliad," from around 800 B.C., describes the heroes of the Trojan War driving to battle in horse-drawn chariots, before dismounting to fight on foot. Troy itself, Homer said, was famed for King Priam's magnificent herds of horses — and the trick of the Trojan Horse sealed the fate of the city.

The invention of an effective saddle and stirrup, along with larger breeds of horses that could carry a rider in heavy armor, gave mounted warriors a decisive edge. Simple stirrups were used in India and China from around 500 B.C., and the use of heavily armored mounted warriors, known as cataphracts, developed in the Median and Persian kingdoms of ancient Iran at about the same time.

Horses and mounted cavalry have played a major part in almost every major war ever since — from the nearly nonstop wars of the post-Roman world, to the Hun and Mongol invasions, to the Muslim conquests and the Crusades; in the New World, the Napoleonic Wars, and the Crimean War, where the Light Brigade made its famous charge; and in the many colonial and territorial wars waged around the globe in recent centuries.

The extensive use of horses in combat did not end until the era of modern warfare, when, trucks, tanks and machine guns began to make the creatures obsolete. Several horse charges were carried out during World War I, but only a few were used in World War II. One of the last instances of horses in warfare was a successful charge by the Savoia Cavalleria, an Italian horse regiment, against Russian infantry at Isbushenskij, on the Eastern Front, in 1942.

Dolphins

The U.S. Navy has been training bottlenose dolphins to carry out marine patrols since the 1960s, after they were identified for their intelligence and military aptitude in a program of tests of 19 different types of animals, including birds and sharks.

A dolphin’s main military asset is its precise echolocation sense, which lets it identify objects underwater that would be invisible to human divers. Dolphins also use their eyes underwater, but by emitting a series of high-pitched squeaks and listening for the echoes that bounce back, they can make a mental image of objects they can’t see.

U.S. Navy dolphins are deployed with teams of human handlers on patrols of Navy harbors and other shipping areas to look for threats such as marine mines, or "limpet bombs" attached to the hulls of warships. The dolphins are trained to spot strange objects and report back to their human handlers with a type of "yes" and "no" response. The handler can follow up on a "yes" response by sending the dolphin to mark the object's location with a buoy line.

These mine-marking abilities came in handy during the Persian Gulf War and in the Iraq War, when Navy dolphins helped clear mines from the port of Umm Qasr in southern Iraq. U.S. Navy dolphins are also trained to help people having difficulty in the water, and to locate enemy divers or swimmers. But, the Navy denies rumors it has trained dolphins to attack, or to use underwater weapons.

Bees

The ancient Greeks and Romans are among many ancient peoples known to have used bees as tiny weapons of war. Attackers would sometimes catapult beehives over the walls of besieged cities, and the defenders of Themiscyra, a Greek town famous for its production of honey, defeated the attacking Romans in 72 B.C. by sending swarms of bees through the mines that had been dug beneath their walls.

The Romans seem to have an especially bad history with bees. In 69 B.C., the Heptakometes of the Trebizond region in Turkey tricked invading soldiers under the command of the Roman general Pompey by leaving hives filled with poisoned honey along the route of their march. Chemists now think the poison was a grayanotoxin that can form in honey, which is rarely lethal to humans but makes them very sick, and the Heptakometes were able to easily defeat the vomiting, intoxicated Romans.

At the Battle of Tanga, in German East Africa (now Kenya) during World War I, both the invading British forces and the defending Germans were attacked on the battlefield by swarms of angry bees, which caused the British attack to fail when a swarm drove off one of their infantry regiments. British propaganda from the time portrayed the bee attack as a fiendish German plot that used trip wires to aggravate the hives of the insects.

During the Vietnam War in the 1960s and 1970s, Viet Cong guerillas were said to have carefully relocated wild hives of the Asian giant honeybee, Apis dorsata, along the trails used by enemy patrols. One fighter would wait nearby until a patrol approached, before setting off a firework near the hive to aggravate the bees and attack the enemy soldiers.

Cattle

Stampeding cattle are one of nature's irresistable forces. They have been used many times in the history of warfare in attempts to crush opposing forces — but often with mixed results.

At the Battle of Tondibi in West Africa in 1591, the defending army of the Songhai Empire opened the engagement with a charge of 1,000 stampeding cattle against the lines of Moroccan infantry — a tactic that had worked in the past against enemies who had no guns. But the Moroccans did have guns, which spooked the cattle. The creatures stampeded back into the Songhai army, who lost the battle and eventually lost control of their empire as a result.

In 1671, the Welsh buccaneer Henry Morgan (later Sir Henry, and the British governor of Jamaica), led an army of 1,000 pirates and freebooters to attack the Spanish colony of Panama City. The Panamanians had only 1,200 troops to defend the city, but they also deployed a herd of 2,400 wild cattle, which they planned to stampede into the pirate army.

But, the pirates stationed themselves behind a patch of swampland, which made the Panamanian cavalry and cattle charges impossible. The wild bulls were finally released late in the battle, but the pirates managed to divert the stampede by waving rags at the charging bulls, and eventually shot down all the poor beasts with muskets.

Morgan and the pirate army went on to capture and sack Panama City, which burned down a few days later, after several mysterious fires broke out. It was rumored that Morgan himself ordered the city to be burned so his drunken pirate army would be forced to move on elsewhere.

Mosquitos

Late in World War II, the German military forces in control of Italy ordered the flooding of the Pontine Marshes south of Rome, in an effort to create a malaria-filled swamp that would slow the Allied advance. The marshes had been drained in a major development project in the 1920s and 1930s. But after Italy changed sides in 1943, and German forces took control of the country, they ordered the pumps that kept the marshes under control to be stopped.

Soon the marshes started to fill with brackish water, which pro-Nazi scientists had foretold would encourage the return of the malarial mosquito species Anopheles labranchiae to the marshes, as well as causing long-term damage to the agriculture of the region.

Over the months that followed, the Allies and Germans fought several "Battles of the Swamps" in the Pontine Marshes, as the water and mud got deeper and amid worsening outbreaks of mosquito-borne malaria that badly affected soldiers on both sides.

But in the end, the mosquitos and malaria were not enough to stop the Allied advance. After the war the Pontine Marshes were drained once more, and the region has been free of malaria since the 1950s.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus