Flowers Evolve to Suit Birds and Bats

The varying shapes of flowers found in tropical forests, from broadly blooming to delicately narrow, may have to do with what has stuck its nose in there to pollinate in past evolutionary eras.

Different species of birds and bats may have encouraged flowers to evolve to fit the shape of their snouts or beaks, new findings suggest.

Flowers seem to respond to whatever is available and doing the best job of spreading pollen, said study leader Nathan Muchhala, a University of Miami biologist. Birds and bats have also changed their body shapes over time to adapt to available food sources and flower and plant shapes, but flowers have done so more aggressively, he said.

"Basically, the flowers are making an evolutionary decision," he told LiveScience. "Organisms can specialize in something (like having wide or narrow openings), but they have to make the tradeoff to be good at one or the other."

The findings are detailed in this month's issue of the American Naturalist.

If the snout fits

Biologists have long observed that pollinators such as birds and bats seem to favor different shapes and species of flowers. However, there has never been evidence to support the idea that flower diversity is a direct result of the need to "choose" one shape over another depending on the pollinator.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

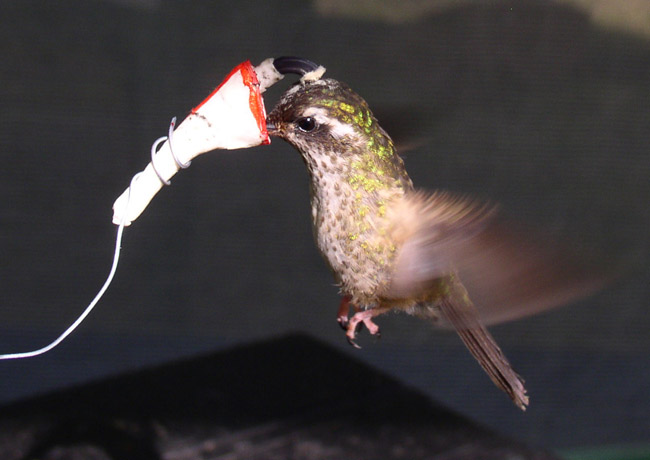

To test this, Muchhala and his team captured (and later released) a species of nectar bat and hummingbird in the rainforests of Ecuador and brought them together with a variety of artificial flowers—filled with honey water—like the ones found locally.

Flower-pollinator fit was crucial in successful pollination, the results showed.

The hummingbirds, with their long and thin beaks, were better guided by flowers with similarly narrow shapes. On the other hand, the much larger bats made better contact with flowers that had wider openings.

Lots of pollen dropped to the ground and was wasted by each animal when the reverse was tested, Muchhala said, and also forced the animals to fly in at odd—and probably uncomfortable—angles.

It has probably been a bit of a give and take relationship over the years, Muchhala said, with the flowers doing most of the evolutionary work.

"There is definitely some degree of co-evolution (simultaneously adapting together), which you can see just in the fact that flower visiting bats and birds have longer snouts than other bats and birds," he said. "However, flowers seem to respond faster."

There isn't just one flower species per bat or bird, Muchhala clarified.

"This is a common misconception—that is, that each flower has its bat/bird specialist, and they are tightly interdependent," he said. "The one exception is a bat with an extremely long tongue (140 percent of body length!) that I recently discovered in Ecuador—a flower with a matching tube length is exclusively specialized to this bat," he said.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus