Underground Railroad secrets revealed with drones, lasers and radar

The escape network helped freedom seekers flee enslavement in the southern U.S.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Archaeologists and historians have uncovered new insights about the Underground Railroad and the people who risked their lives to escape enslavers in 19th-century America. With technologies such as thermal drones and laser pulses, scientists have peered through overgrown vegetation and under the ground to find tunnels, caves and refuges that offered respite along the dangerous journey to freedom.

Many freedom seekers fleeing slavery in the United States found a hard-won path to liberty through a system of secret routes, safe houses and hidden way stations known as the Underground Railroad. This escape network operated from roughly 1830 to the outbreak of the Civil War in 1861, and it arose during the brutal period in the U.S. when white people in Southern states routinely kidnapped, tortured and enslaved African people and their American-born descendents.

Because secrecy was critical for ensuring freedom seekers' safety and keeping the routes open, many of the details surrounding the Underground Railroad were thought to be lost. However, recent archaeological discoveries and new analysis of historic archives are shedding light on the individuals who forged and followed the secret routes. Their stories are revealed in the new four-part docuseries "Underground Railroad: The Secret History," which debuted Jan. 30 on the Science Channel and is streaming on discovery+.

Related: 4 myths about the history of American slavery

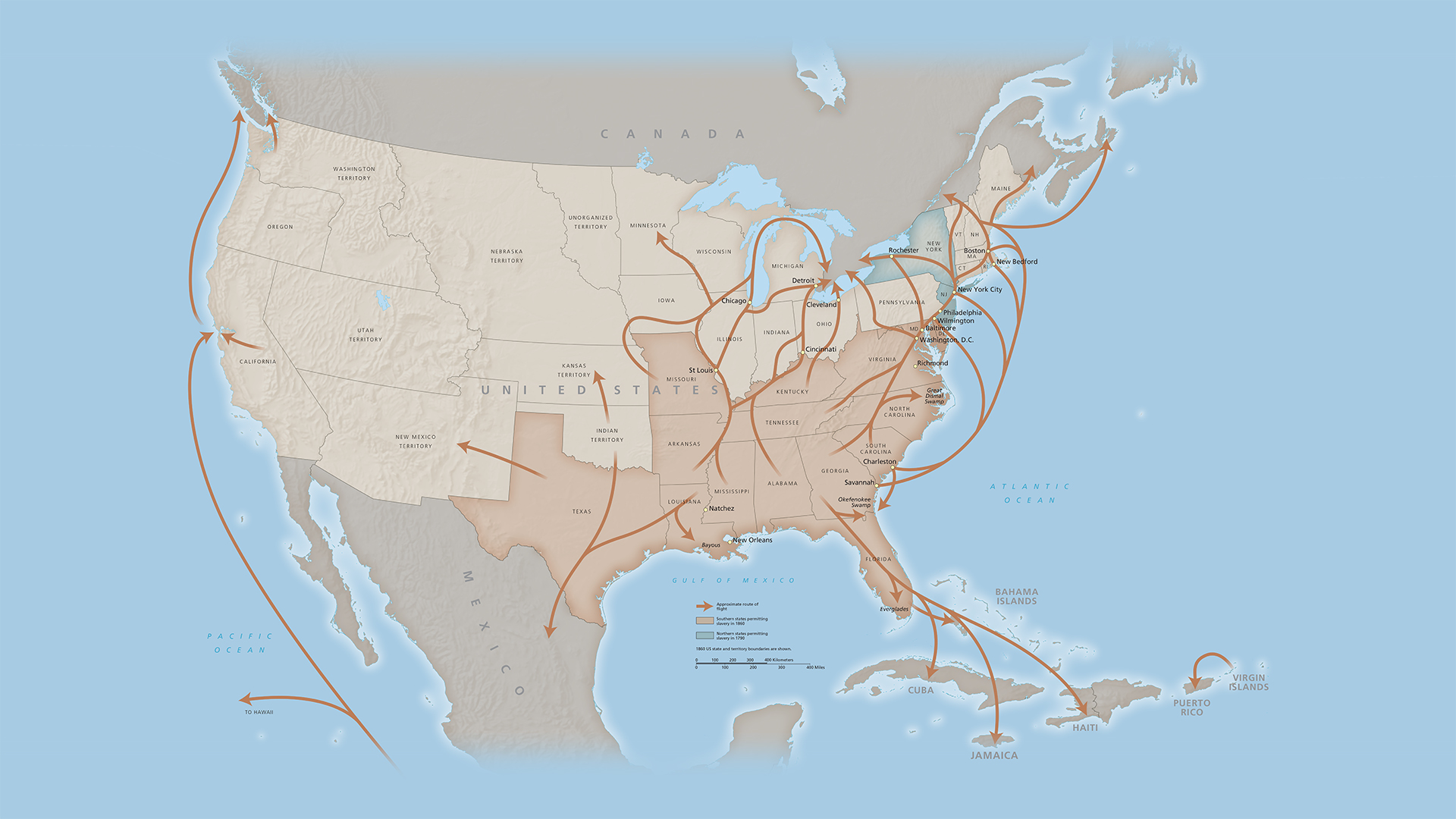

Routes along the Underground Railroad frequently followed natural waterways as well as human-made roads and trails, and led from places of enslavement in the South to Northern and Western states where slavery was illegal. Freedom seekers also used these routes to escape to Canada, Mexico, Florida, Caribbean islands and Europe, according to the National Park Service (NPS).

Some known Underground Railroad destinations are now recognized as historic landmarks, such as the Jackson Homestead in Newton, Massachusetts, and the Bethel AME Church in Greenwich Township, New Jersey, according to the NPS.

In the docuseries, researchers in Texas turned to geographic information system (GIS) mapping to match data from historic maps with modern topography and find secret boat landing locations where freedom seekers fled into Mexico, Science Channel representatives told Live Science. The search area included a river path that has changed dramatically over the centuries, so GIS was essential in finding the secret spots, the representatives said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

In Prospect Bluff, Florida, a former Spanish fort that was an important stop on a southern branch of the Underground Railroad was all but forgotten until researchers detected the fort's contours by pinging the landscape with beams of near-infrared light in a technique known as light detection and ranging, or lidar. In Kansas and Ontario, lidar turned up "buried remnants of 1800s structures at former Underground Railroad-connected sites in towns that no longer exist," Science Channel representatives said.

And in South Carolina, scientists turned to magnetometry — a technique that measures small shifts in Earth's magnetic field to identify certain metals — to find a sunken Confederate ship that was famously captured by freedom seeker Robert Smalls. Smalls liberated himself and his family from slavery in 1862 when he commandeered the CSS Planter, sailing it from Confederate waters into a Union blockade, according to the Iowa Department of Cultural Affairs.

Written records

New attention to old records is also playing a part in reconstructing the places and people of the Underground Railroad. Though there are plenty of documents dating to the time when the network was active, most were overlooked by the academic community, under the assumption that no one would have kept records about such a clandestine and risky operation, said historian Anthony Cohen, president of The Menare Foundation, a nonprofit organization dedicated to preserving Underground Railroad history.

Cohen, a consultant for the new docuseries, told Live Science that in recent years, researchers have identified many firsthand sources that hold valuable information about how people built, maintained and used that secret escape route.

"Slave narratives, autobiographies, newspaper reports, court records — people were caught in the act and prosecuted — those records remain to tell the story," Cohen said. The rise of the internet and initiatives by museums and archives to digitize records and make them available digitally have also broadened access to details from the Underground Railroad, he added.

"As those records have been more broadly broadcast and more deeply understood, other information has followed," Cohen said. "We have a very clear picture of how the Underground Railroad operated — if not every place it operated — and we're constantly discovering more."

Originally published on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is a science journalist and author of "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind-Control" (Hopkins Press). She formerly edited for Scholastic and was a channel editor and senior writer for Live Science. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to LS, she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in NYC. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post, How It Works Magazine and CNN.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus