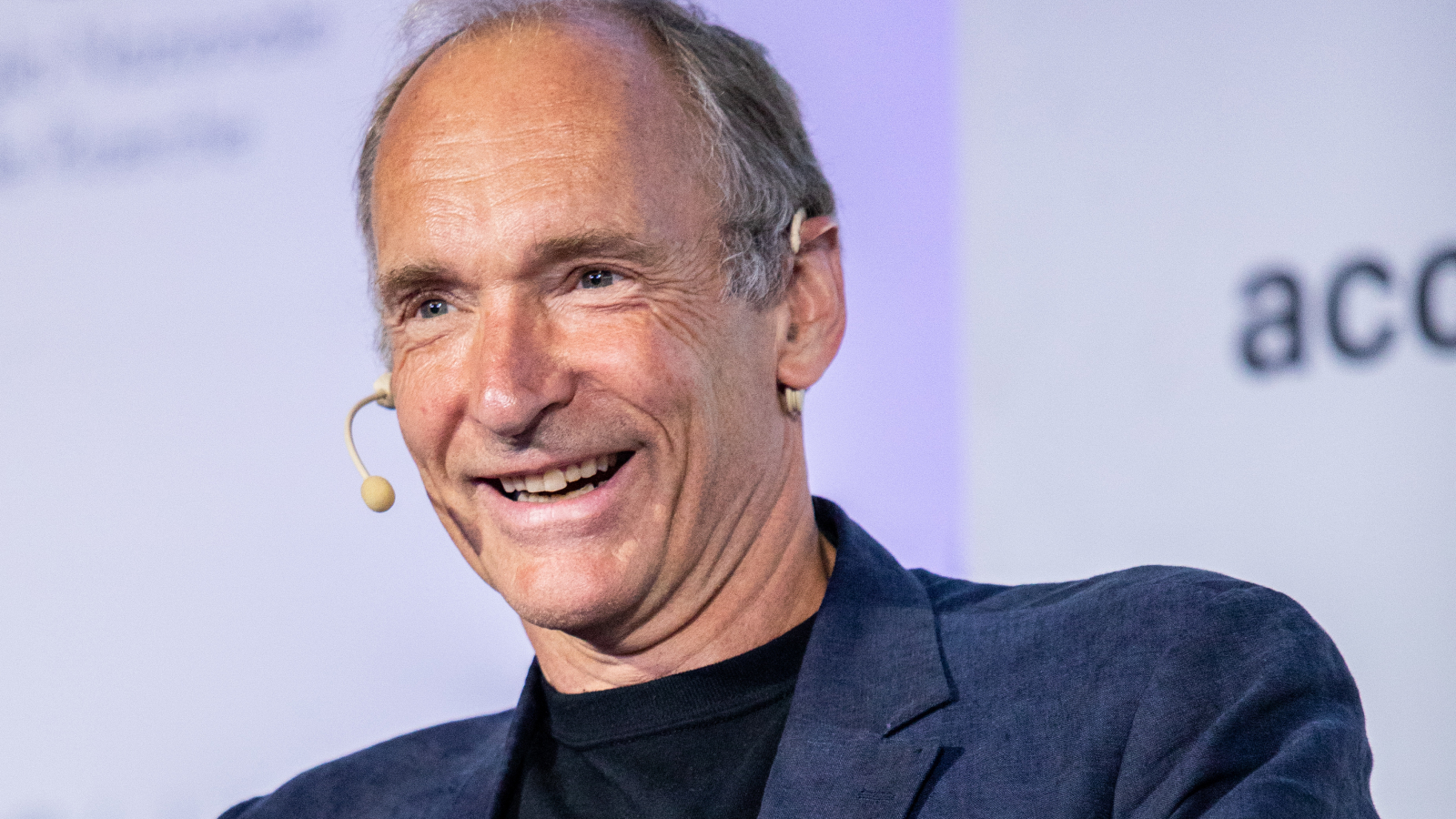

35 years after first proposing the World Wide Web, what does its creator Tim Berners-Lee have in mind next?

After seeing the balance of power shift to large corporations and big tech companies, the founder of the World Wide Web is determined to give users control over their data again.

When computer scientist Tim Berners-Lee sent a memo detailing his idea of a "distributed hypertext system" on March 12, 1989, it was largely ignored by his colleagues at CERN, the European Organization for Nuclear Research. This is not surprising: CERN is a place where scientists build huge colliders, not a think tank for computer geeks. Why should they care about one man's curious idea to create an interlinked web of information?

The answer was that he was trying to make their lives easier. Several thousand scientists worked at CERN at the time, but information about their projects sat in silos. Linking them together through one extended network of computers seems obvious now, but it took 18 months before Berners-Lee was granted permission to dedicate time to his idea.

He published the first web page for CERN users in December 1991 and freely distributed his software the following year. Exponential growth soon followed. By 1994, with over 10,000 web servers online, Berners-Lee saw the need for standards. He moved from CERN to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), where he founded the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C) to ensure that the web's royalty-free, open nature was baked into its principles.

Related: Internet history timeline: ARPANET to the World Wide Web

He also started talking about "the semantic web." This concept is built upon metadata and relationships — think of it as a machine-readable version of the internet that adds both context and structure.

Using this, "you can ask things like, 'let me listen to music which has been written by people who were born in towns in Minnesota with less than 200,000 inhabitants,'" Berners-Lee said in an InfiniteMIT video in 2010. In short, because information has been linked together — and is openly accessible — it can be used in original, unpredictable ways. Such a concept can't work if the data is siloed or controlled by corporations.

Pushing for a more open web

Berners-Lee helped to set up the World Wide Web Foundation in 2009, which aims to"[fight] for a world where everyone has affordable, meaningful access to a web that improves their lives and where their rights are protected.".

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

For the past decade, he has also pushed for the third evolution of the web, which he dubs "Web 3.0." This often gets confused with Web3, but they are very different: Web3 is based entirely around the use of blockchain to build a decentralized internet, with cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin used to trade. Web 3.0, by contrast, stays true to the founding principles of being open and royalty-free. It also builds on the two key ideas of the semantic web and giving people control over their data.

In 2016, Berners-Lee created the Solid protocol, a "single sign-on across the web," he told CNBC's Beyond The Valley podcast in February 2023. "And then you give everybody [their] own personal cloud storage, call it a Solid pod, they have complete control over that."

Rather than hundreds of companies controlling the data you have provided to them, as is the status quo, any app creator can access your data, or a portion of it, by tapping into your pod, with your permission. Berners-Lee used the example of sharing data with a vacation-planning app at the Global Freight Summit in November 2023. "So I'm going to show you all the data in my pod about all of the other family vacations that we've had before, just for the purposes of helping me find the next one. Then it will all vanish, [the app] won't have access anymore."

For Solid to work, Berners-Lee realized he needed to talk to governments and enterprises. That's why he set up Inrupt with co-founder John Bruce. The idea behind the company, Bruce told the Beyond The Valley podcast, was to "galvanize the efforts" around the Solid protocol and build "an enterprise-grade version of it all." The venture aims to make Solid safe and scalable so it can be used by governments and massive organizations who want to use data in a more ethical and consensual way.

Can the internet's creator make Web 3.0 a mainstream idea?

In the five-and-a-half years since its foundation, Inrupt has scored some successes. It worked with the Flemish government to create a "data utility company" called Athumi, giving consumers and businesses within Flanders their own pods in which they can store their personal data. This system enables users to control and share data, for example to share career data with prospective employers and smartwatch data with doctors.

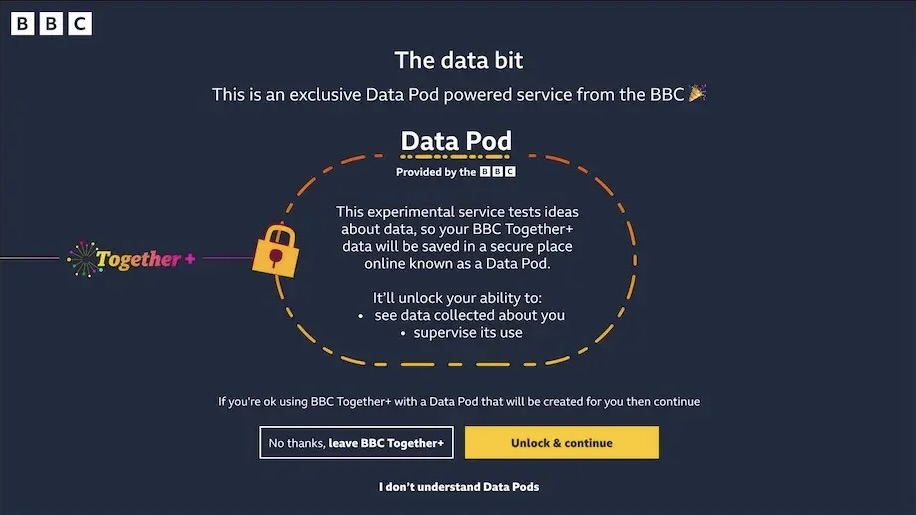

In 2022, the BBC also partnered with Inrupt to launch a six-month trial called "BBC Together + Data Pod" to give viewers control over their data when taking part in a watch party on its streaming service, iPlayer.

Max Leonard, principal technologist at Inrupt, told VideoWeek that "there was only a small number of people who were really bothered by [the data side of it], but they went into quite a lot of detail." He added: "But most people just wanted to get on and use the thing."

Inrupt's website also notes "customers" such as the U.K. and Swedish governments, British bank Natwest and the British National Health Service (NHS). There are also three American organizations including the insurance company Allstate, Brooklyn-based climate tech company BlocPower and the Bezos Earth Fund.

So far, then, Inrupt has not had an explosive impact. But Berners-Lee cites people's growing awareness of their personal data as a key driver of change. "People will realize that basically anything which works and doesn't give them data in their pocket is kind of robbing them of the power," he told the Beyond The Valley podcast. "There won't be suddenly a day when everything switches across, but just incrementally and inexorably, everything will be moving into this new, much more powerful world."

Tim Danton is a journalist and editor who has been covering technology and innovation since 1999. He is currently the editor-in-chief of PC Pro, one of the U.K.'s leading technology magazines, and is the author of a computing history book called The Computers That Made Britain. He is currently working on a follow-up book that covers the very earliest computers, including The ENIAC. His work has also appeared in The Guardian, Which? and The Sunday Times. He lives in Buckinghamshire, U.K.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus