How big can snowflakes get?

What is the largest snowflake ever recorded?

In 1887, a rancher named Matt Coleman spotted huge snowflakes that had fallen onto one of his cattle pastures in western Montana during a snowstorm and declared them as "larger than milk pans."

With a width of 15 inches (38 centimeters) and a thickness of nearly 8 inches (20 cm), these colossal flakes currently hold the record for being the largest snowflakes ever recorded, according to Guinness World Records.

Despite there being no photographic evidence of the jumbo-size snowflakes, they remain a popular piece of precipitation trivia. But it does raise the question: Is it even possible for a single snowflake to form to be the size of a dinner plate? And, what's the biggest a snowflake can really get?

Kenneth Libbrecht, a physics professor at the California Institute of Technology, said such monster flakes are rare but not impossible. That's because there's a common misconception of what makes a snowflake an actual snowflake.

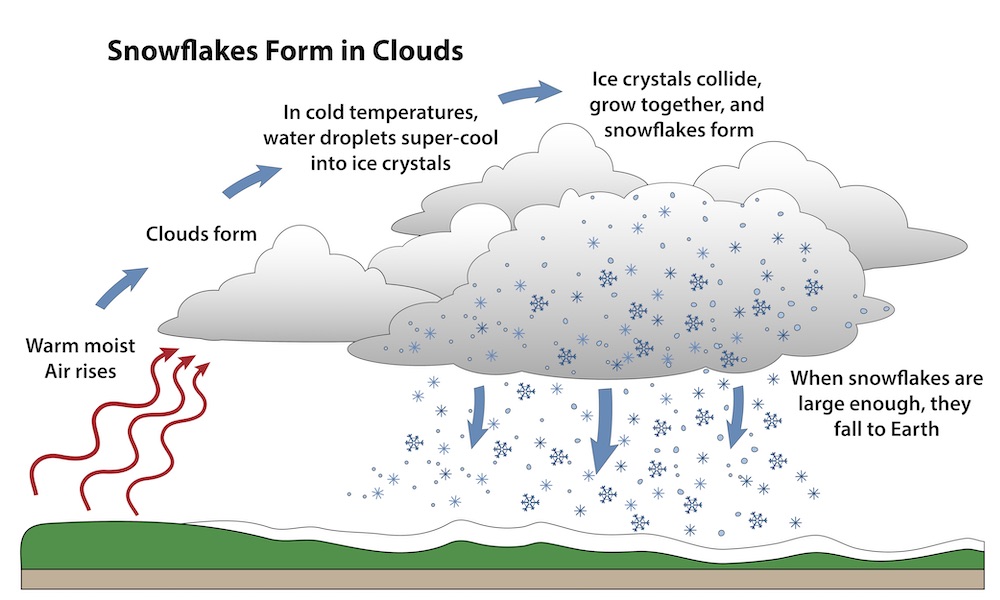

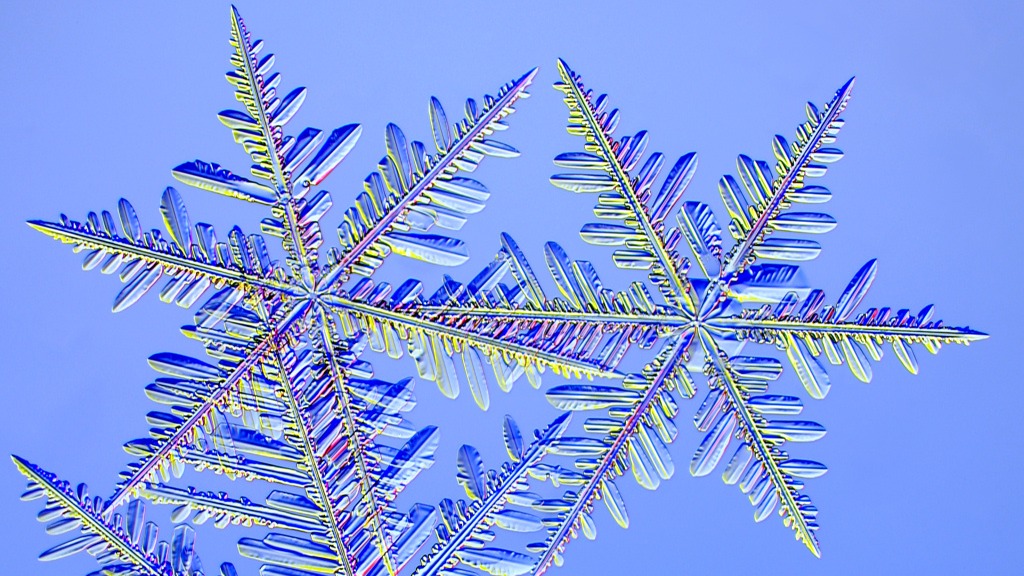

When people talk about snowflakes, what they're actually referring to are snow crystals, which are single crystals of ice within which the water molecules line up in a hexagonal pattern that causes them to "display that characteristic six-fold symmetry we are all familiar with," Libbrecht told Live Science.

Related: How much snow if needed for an official 'White Christmas?'

Snowflakes, on the other hand, can encompass everything from an individual snow crystal to hundreds or even thousands of snow crystals that smash and stick together in midair as they fall to the ground to form clusters or aggregates.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

In cold places, "you see them all the time, these big puffballs falling out of the sky," Libbrecht said, "They're not snow crystals; people call them snowflakes, but I like to call them puffballs because that's more indicative of what they're shaped like."

So, it's possible that the infamous gobs that Coleman saw on his cattle ranch more than a century ago were simply a bunch of ice crystals that had collided together to form one aggregated snowflake.

However, the typical size of a snow crystal is far smaller.

After spending much of his career studying and photographing snow crystals, including writing several books and creating a website dedicated to the topic, Libbrecht said that the largest snow crystal he's ever spotted in the wild was a "monster."

"It's the biggest one I'd ever seen, about 10 millimeters, [0.4 inches]" Libbrecht said. "It was about as big as a dime."

In his lab, under controlled conditions where there's no wind to shred snow crystals apart in midair and temperatures can be set to an ideal 5 degrees Fahrenheit (minus 15 degrees Celsius) — perfect for snow crystal formation, Libbrecht said — he's "easily seen" crystals grow to similar sizes.

"That's about as big as they get," he said. "I've been studying this for a while and I know a lot of other snowflake photographers, and we compare notes. Ten millimeters — that's a big one."

The reason snow crystals top out at that size is due to the wind.

"The main limit on size is just that these large crystals are quite fragile," he said. "They have to grow quickly, and if there is any wind they break apart. So the weather conditions for making such large crystals are rare."

Although snow crystals may be small in stature, the variety of shapes they can take on is astounding. In the 1930s, Ukichiro Nakaya, a Japanese physicist who produced the world's first artificial snowflakes, documented their many different shapes in a morphology diagram, which, depending on the temperature and humidity at which they form, can range from simple prisms and columns to more detailed rosettes and fernlike stellar dendrites.

For example, six-armed dendrites begin forming at below freezing while columns take shape at around minus 10 degrees Fahrenheit (minus 25 degrees Celsius).

"When you grow them in the lab you can see what happens under different conditions," Libbrecht said. "It's remarkably diverse growth. Not all crystals grow under such a diversity of shapes, that's kind of unique to ice."

Jennifer Nalewicki is former Live Science staff writer and Salt Lake City-based journalist whose work has been featured in The New York Times, Smithsonian Magazine, Scientific American, Popular Mechanics and more. She covers several science topics from planet Earth to paleontology and archaeology to health and culture. Prior to freelancing, Jennifer held an Editor role at Time Inc. Jennifer has a bachelor's degree in Journalism from The University of Texas at Austin.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus