Never-before-seen colossal comet on a trek toward the sun

A week after astronomers noticed a new object in the sky, they've identified it as a comet.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

A new visitor is swinging by the solar system: a never-before-observed comet that hails from the Oort Cloud.

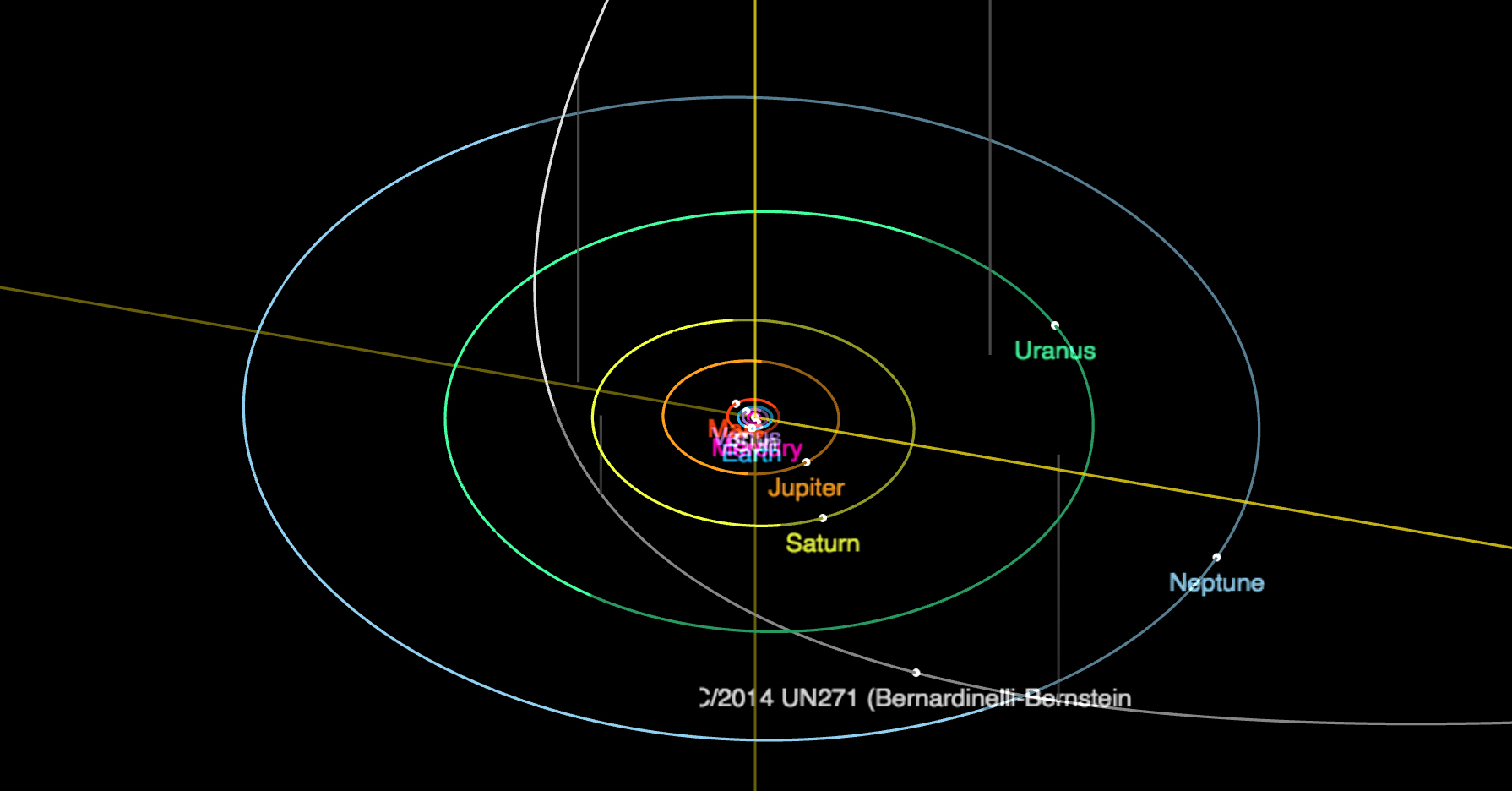

This alien object was just designated as a comet Wednesday (June 23), only a week after astronomers first observed it as a tiny, moving dot in archival images from the Dark Energy Camera at the Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory in Chile. The comet is now known as Comet C/2014 UN271, or Bernardinelli-Bernstein after its discoverers, University of Pennsylvania graduate student Pedro Bernardinelli and astronomer Gary Bernstein.

The comet, which may be an impressive 62 miles (100 kilometers) wide, is 20 times the distance from Earth to the sun away, heading toward our blue dot. It will reach its closest point to the sun in its orbit on Jan. 23, 2031, when it will be just beyond the orbit of Saturn, or about 10.95 times the distance between Earth and the sun.

"We will have practically 20 years to study it," said Peter Vereš, an astronomer at the Center for Astrophysics Harvard & Smithsonian and at the Minor Planet Center, which identifies and computes orbits for new comets, minor planets and other far-flung rocky bodies. That's an exciting opportunity, he said, because the comet is likely a near-pristine object from the Oort Cloud, a field of icy, rocky debris that likely surrounds the solar system like a crunchy shell.

Related: The 12 strangest objects in the universe

Unidentified orbiting object

Comet Bernardinelli-Bernstein first made its appearance in the 2014 archives of the Dark Energy Camera. Bernardinelli and Bernstein soon realized that the object, which looked like nothing more than a dot, was moving over time as they traced it through 2015, 2016, 2017 and 2018.

The astronomers sent the observation to the Minor Planet Center, which at first classified the object as an asteroid or minor planet, since its surface appeared to be chemically inert. The report of the new object triggered amateur astronomers to point their telescopes skyward, though, and some soon noticed a "coma," or haze of vapors and dust, emanating from the object.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"They found out, 'Oh look, this object is active,'" Vereš told Live Science.

Comets are active because the sun's heat and solar wind cause gas to release from the surface. It's likely that the surface has become more active over the past few years as the comet streaked closer to the sun, Vereš said, making the activity easier to spot.

A long journey

The comet takes approximately 5.5 million years to complete its orbit, which is vertical to the plane of the planets, Minor Planet Center researchers have calculated. At its farthest point away, it's approximately a light-year from the sun. Based on its orbit, the comet is likely an emissary from a far-off, ice-cold region past the outer edges of the solar system known as the Oort Cloud. Objects like the Bernardinelli-Bernstein comet were probably once part of the solar system, Vereš said, but they were kicked out by gravitational interactions with large planets like Saturn and Neptune.

Though the comet's history isn't certain, this newfound trek may be its first foray back into the solar system since its initial banishment, Vereš said. That's exciting, because the short-periodicity comets that circle within the solar system are significantly altered from their original form, baked and diminished by many rotations around the sun. Long-periodicity comets like Bernardinelli-Bernstein that stay in the outer parts of the solar system don't change as much, meaning they're a time capsule of conditions at their formation in the early days of the solar system.

"We are receiving more and more observations basically every day," Vereš said. To the eye, the comet still looks like a fuzzy dot and probably won't ever be visually impressive, he said; but sensitive instruments on large telescopes may soon be able to detect variations in the light coming from the comet that can reveal the molecules coming off its surface. These data could reveal what the comet is made of.

Originally published on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus