Oldest American, Hester Ford, dies, leaving 120 great-great-grandchildren

Hester Ford, America’s oldest woman, celebrated her 116th birthday on Aug. 15 at her home in Charlotte. She has died of natural causes. First reported by @qcitymetro. 📸 @TCooperHullPics pic.twitter.com/JVRMYT0NYsApril 17, 2021

Hester McCardell Ford, a woman recognized as the oldest living American, died Saturday (April 17) at the age of 115 — or possibly 116, depending on which census report you read.

Born in Lancaster County, South Carolina, she married John Ford at age 14, The Charlotte Observer reported, and bore the first of her 12 children the next year, at age 15. At the time of her death a century later, she had 68 grandchildren, 125 great-grandchildren and at least 120 great-great-grandchildren.

"She was a pillar and stalwart to our family and provided much needed love, support and understanding to us all," her great-granddaughter Tanisha Patterson-Powe said in an email to the Observer.

Related: Extending life: 7 ways to live past 100

Hester Ford, a Charlotte woman believed to the oldest American, has died. She was at least 115. https://t.co/iIZeWFCPjO pic.twitter.com/Or77PMp4NqApril 18, 2021

Her family noted that some U.S. Census Bureau documents indicate that Ford was born in 1905, while others cite 1904 as her birth year, according to the Observer. Either way, Ford became the oldest living American in November 2020 after the previous record holder, Alelia Murphy, died at 114 years and 140 days old, according to data compiled by the Gerontology Research Group, an organization that tracks "supercentenarians," meaning people who live to age 110 or older.

Hester and John Ford moved to Charlotte, North Carolina, around 1960, and following her husband's death in 1963, Hester Ford lived alone for many decades, until she was 108. She then moved in with family and spent her days singing with relatives, playing games, getting some fresh air and exercise, watching home movies and flipping through old photo albums, her granddaughter Mary Hill told the Observer.

When asked for the secret to her longevity in a 2020 interview with the Observer, Ford responded, "I just live right, all I know." Of course, scientists have their own theories about how supercentenarians like Ford continue to thrive into old age.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

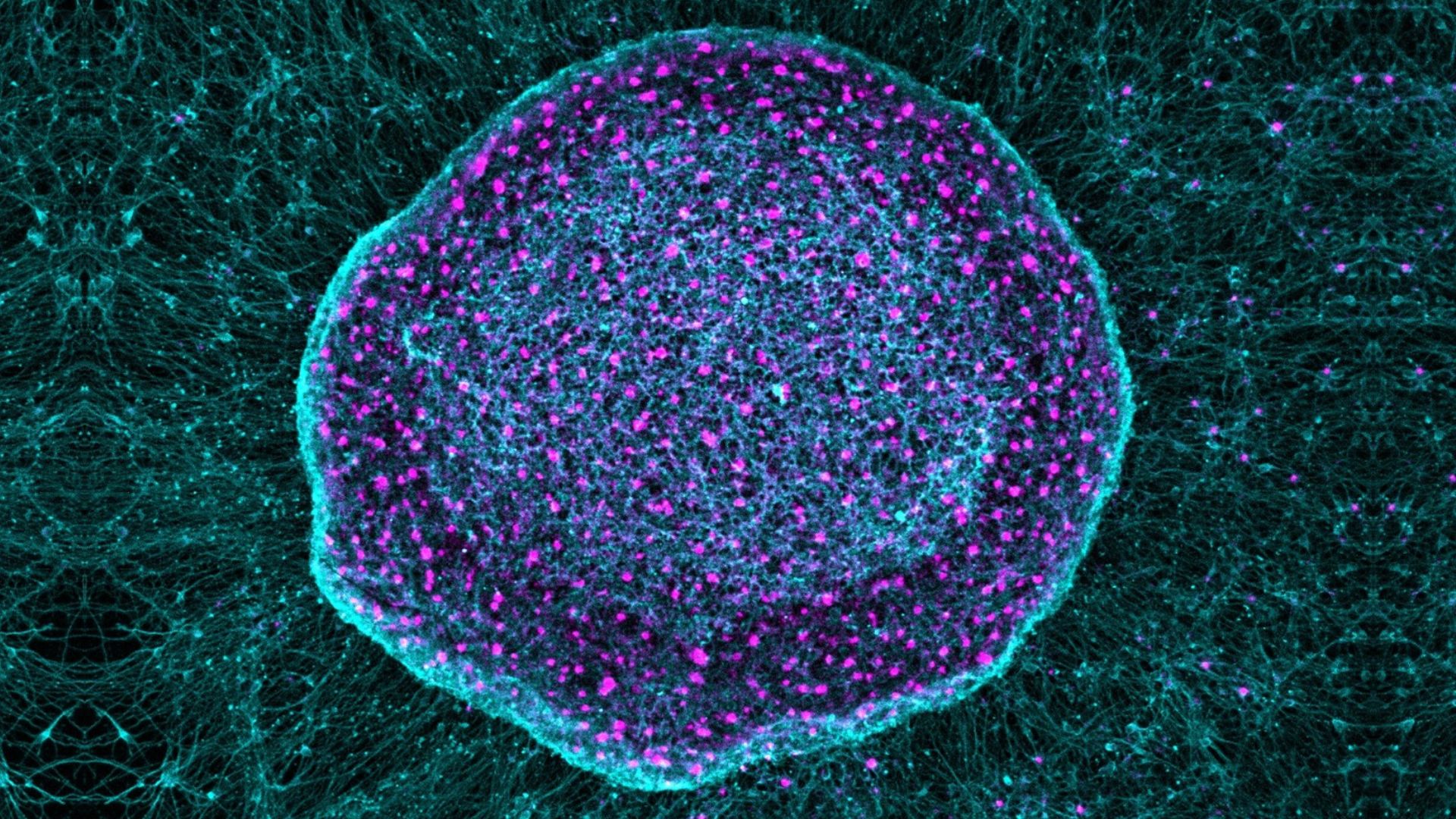

For example, a 2019 study published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences found that supercentenarians may have above-average levels of a rare immune cell in their blood, helping them ward off disease, Live Science previously reported. The cells, called CD4 CTLs, are a kind of T helper cell that can directly attack infected and cancerous cells. In the study, about 2.8% of young participants' T helper cells were CD4 CTLs, compared with 25% in the supercentenarians studied.

Other studies suggest that specific genes may be linked to longevity. For example, variants of the ABO, CDKN2B, APOE and SH2B3 genes may be more common in centenarians than in people who live an average life span; these variants may help reduce the risk of certain age-related diseases, such as heart disease and Alzheimer's.

Beyond biology, lifestyle and psychological factors may also help people survive for impressive periods of time. According to some research, optimistic people tend to live longer than pessimistic people; this may be because having a rosy attitude helps "foster health-promoting habits and bolster resistance of unhealthy impulses." (Granted, that may also be a bit of a "chicken-or-the-egg" question.)

Certain diets have also been linked to longevity, but the science behind how a reduced-calorie or moderate-carb diet might extend life span, and in which people, remains fuzzy.

For the record, Hill said her grandmother typically started her day with a breakfast of grits, pancakes, waffles or oatmeal, according to the Observer. Then, she'd have sausage or bacon with a side of eggs, a piece of toast and half a banana.

Read more about Ford's life in The Charlotte Observer.

Originally published on Live Science.

Nicoletta Lanese is the health channel editor at Live Science and was previously a news editor and staff writer at the site. She holds a graduate certificate in science communication from UC Santa Cruz and degrees in neuroscience and dance from the University of Florida. Her work has appeared in The Scientist, Science News, the Mercury News, Mongabay and Stanford Medicine Magazine, among other outlets. Based in NYC, she also remains heavily involved in dance and performs in local choreographers' work.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus