'Powerful, maybe even frightening' woman with diadem may have ruled in Bronze Age Spain

This is only the sixth known diadem from ancient Spain.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Archaeologists in Spain have discovered "one of the most lavish burials of the European early Bronze Age": the grave of an elite woman wearing a silver diadem in what might be one of Western Europe's first palaces. She might even have been a queen of sorts who ruled over the realm.

The woman's remains were buried next to a man who was slightly older and died a few years earlier, the researchers found. But the man had far fewer and inferior goods in his grave, raising questions about which individual had more power and whether she was a ruler, according to the study, which was published online Thursday (March 11) in the journal Antiquity.

When interpreting such a burial, it's important to have an open mind about the past, said study co-researcher Roberto Risch, a professor of archaeology at the Autonomous University of Barcelona. "Traditionally, in a very male-dominated academia, you would say, 'Oh, she is the partner of him. He was the big guy — he is a little bit older, and if she is the partner, she is just a beautiful woman and she gets a lot of ornaments," Risch told Live Science.

But given that she outlived the man and still received more opulent goods, it's likely that the woman had power of her own, Risch said. "What she is wearing — it's not because of him, because she is alone," Risch said. "There is no more him around. He died before."

Related: 6 times that showed us women from antiquity were totally badass

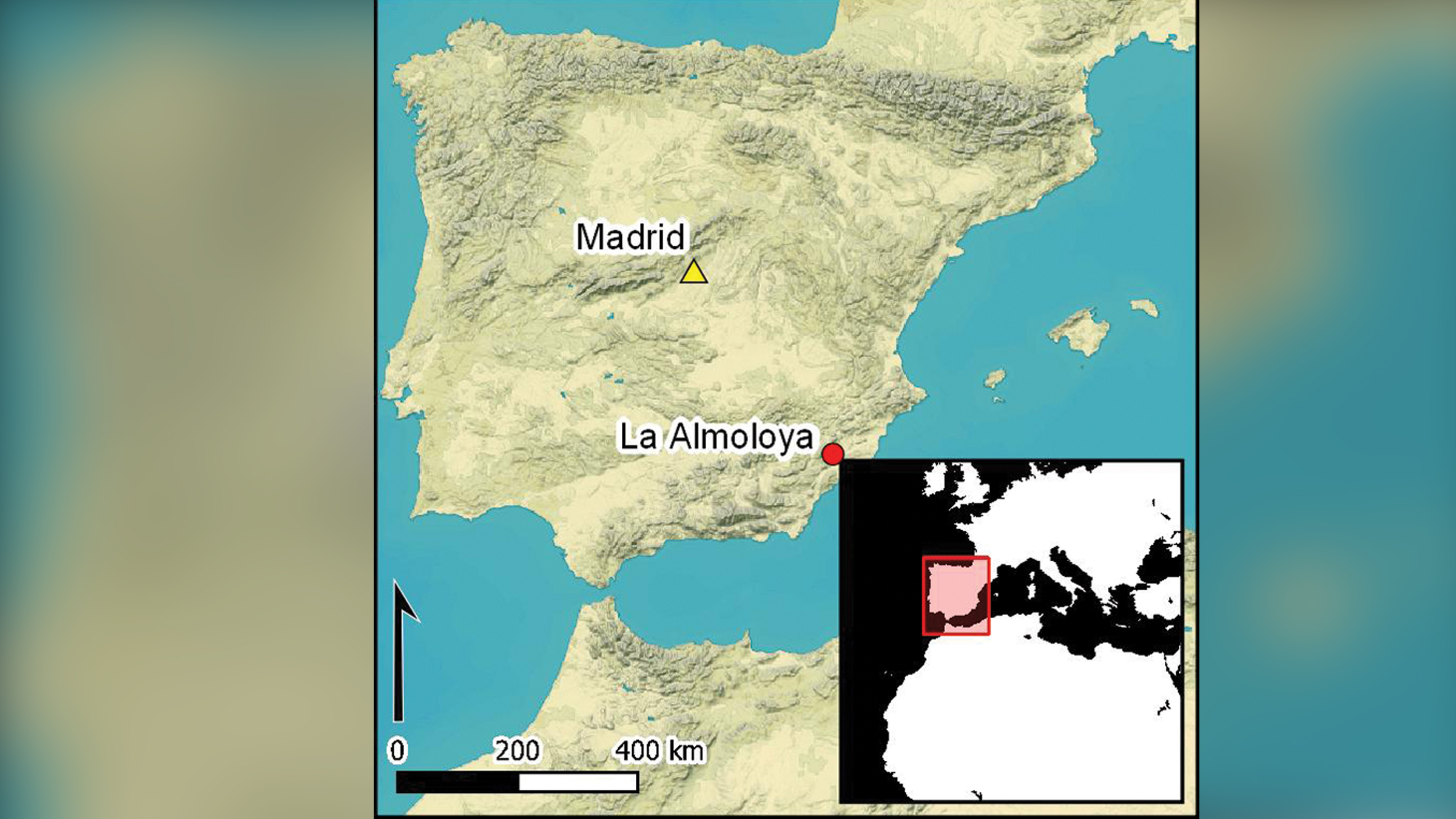

Archaeologists have known about this site — known as La Almoloya, in the southeastern region of Murcia, Spain — since the 1800s, when Belgian mining engineers discovered the ruins of a Bronze Age society there. This economically tiered society, known as El Argar (2200 B.C. to 1550 B.C.), was complex; the Argaric people built monumental structures, grew and processed cereals such as barley and wheat, kept domesticated animals, traded with faraway cultures and practiced metallurgy, according to a 2020 study published in the journal PLOS One.

Over the millennia, grave robbers have pilfered countless El Argar burials. So archaeologists were stunned in August 2014, when they unearthed a pit burial containing a large ceramic pot that held the remains of two individuals — a man who died when he was 35 to 40 years old and a woman who died when she was 25 to 30 — who were buried in the governing hall of a palatial building. Radiocarbon dating showed that they both died in the mid-17th century B.C., but that the man died a few years before the woman; the burial was later reopened for her interment when she died, Risch said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Testing of the ancient DNA at the Max Planck Institute in Germany showed that the man and women were not biologically related but that they had a 12- to 18-month-old daughter buried in a nearby building. A forthcoming study of the daughter's burial will investigate why she was not buried with her parents, said study co-researcher Cristina Rihuete Herrada, a professor of archaeology at the Autonomous University of Barcelona.

The woman was buried wearing the silver diadem, beaded necklaces, silver-crafted rings, bracelets, spiral hairpieces and earplugs with spirals. The inclusion of a silver-rimmed drinking cup suggests that "apparently, she was so noble that her lips are not allowed to touch the drinking pot. The pot is covered with silver foil, so her lips only touch[ed] silver," Risch said. A silver-handled awl for making holes in textiles suggests that she had power over linen production, a thriving industry based on the looms found at La Almoloya, he said.

The man was buried with a beaded necklace, gold earplugs with silver spirals, copper bracelets, silver spiral hairpieces and a copper-bladed dagger. The burial also had a bowl and animal offerings.

The burial's silver, most of it hers, weighs about half a pound (230 grams). To put this burial's riches into context, this amount of silver was enough to pay 938 daily wages or buy more than 7,300 lbs. (3,350 kilograms) of barley at that time, the researchers said.

Silver diadem

Of the 29 treasures found in the burial, the silver diadem is the most valuable; it's one of only six ever found from Bronze Age Spain. Diadems are often interpreted as symbols of rank that were worn by leaders, the researchers wrote in the study. This particular type of diadem — with a flat, mushroom-like circle on the front — could be worn facing upward or downward. (Archaeologists have found it both ways in burials.)

The silver diadem is now corroded, but "to have a woman looking at your eyes with a shiny mirror that looks into you … She must have been quite somebody," Risch said. "The look of this woman must have been very powerful, maybe even frightening."

"The look of this woman must have been very powerful, maybe even frightening."

Roberto Risch

This diadem likely signified that the woman was part of the dominant ruling class, just like crowns found in other Bronze Age societies, including the Wessex culture in what is now the southern U.K. and the Únětice culture in what is now Central Europe, Rihuete Herrada said.

Moreover, other burials from the El Argar culture show that upper-class women were often buried with posh, gender-specific goods, often starting at about age 6, while men weren't given this honor until about age 12, Rihuete Herrada told Live Science. This suggests that "girls would acquire this gender status earlier than boys," she said.

But it's an ongoing question of what gender meant in the El Argar society. In the case of this tomb, "we have class and gender working together," Rihuete Herrada said.

So, were the woman's diadem and other treasures emblems of power, or merely burial ornaments? The researchers are leaning toward the former, they said.

"In the Argaric society, women of the dominant classes were buried with diadems, while the men were buried with a sword and dagger. The funerary goods buried with these men were of lesser quantity and quality," they said in a statement. "As swords represent the most effective instrument for reinforcing political decisions, El Argar dominant men might have played an executive role" in maintaining order, but perhaps the women were the ones making the political decisions, they said.

Next, the researchers plan to study marks left by muscles on the El Argar's people's bones to see how they handled the division of labor, Rihuete Herrada told Live Science. An analysis of the skeletons found in the ceramic pot revealed both had marked health conditions. The man had a healed head injury and bone wear and tear that likely came from extensive horseback riding.

Meanwhile, the woman had several congenital conditions, including a missing neck vertebra and rib, two fused lower vertebrae and a short left thumb, as well as rib markings that might indicate a heart infection. "She would have a shorter neck; she would have a special thumb. If you couple that with all these jewels that transform her aspect, that would add to her singularity amongst that community," Rihuete Herrada said.

The public will be able to see the artifacts from the burial and other El Argar sites, as well as a virtual 3D Bronze Age settlement with goggles, in Mula and Pliego, Spain, once pandemic restrictions lift, Risch said.

Originally published on Live Science.

Laura is the managing editor at Live Science. She also runs the archaeology section and the Life's Little Mysteries series. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus