Top skywatching events to look forward to in 2021

From meteor showers to eclipses, there's some exciting stuff that will happen in the night sky next year.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Looking up at the night sky has captivated people since ancient times, with glowing and sometimes unexplained phenomena lighting up the heavens. Celestial, planetary or other phenomena that take place only sometimes and that occur high above our heads captivate, entertain and bring a certain joy to our curious minds. From meteor showers to eclipses, here are the most exciting skywatching events to look forward to in the new year.

Quadrantids meteor shower (January)

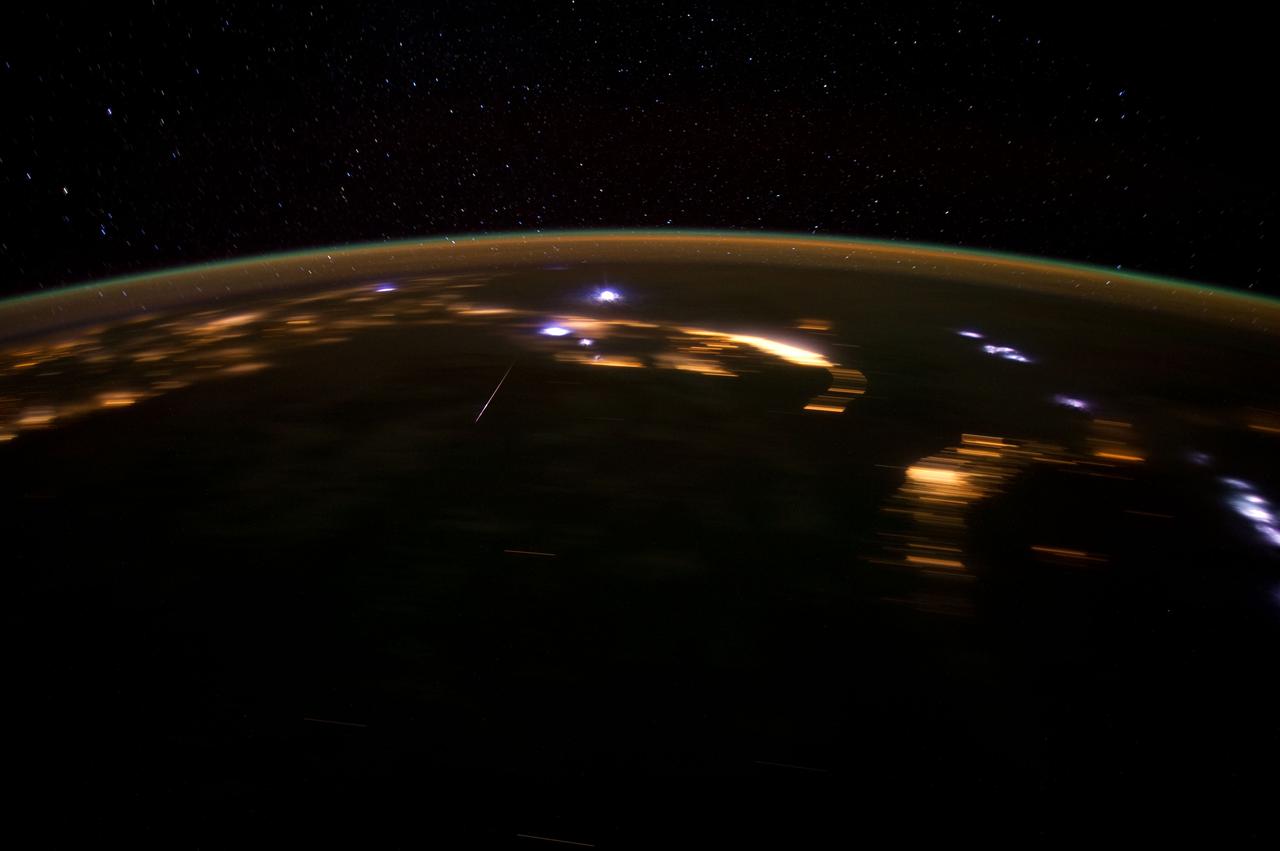

The new year will start out with some shooting stars, and (hopefully) some chances to wish upon them. The Quadrantids meteor shower, one of the best annual meteor showers, will peak on the evening of Jan. 2 through the early morning hours of Jan. 3, according to NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Though light from the moon (which will be about 84% full at the time) may make the skies too bright to see most of the meteors, some more spectacular ones may be visible, according to Earthsky. You will have better luck at seeing them if you're in the Northern Hemisphere. And compared with other meteor showers, the Quadrantids' peak is very short, only lasting a few hours on Jan. 3 at 9:30 a.m. EST (14:30 UTC), according to the International Meteor Organization. That would mean that western North America would have a good view of the meteor shower before dawn on Jan. 3, according to Earthsky.

Lyrids meteor shower (April)

The Lyrids meteor shower is one of the oldest known; the first sighting of the shower dates back to 687 B.C., according to NASA. This year, they will run from April 16 to April 25 and peak before dawn on April 22 after moonset, according to Earthsky. The Lyrids can bring up to 100 meteors per hour, but on average about 10 to 15 meteors per hour can be expected during the peak, according to Earthsky. The space debris that interact with the planet's atmosphere to form the Lyrids comes from the comet C/1861 G1 Thatcher, according to NASA. These beautiful meteors tend to leave behind a glowing dust train that can be seen for several seconds.

Eta Aquarids meteor shower (May)

This meteor shower will provide the best show for those in the Southern Hemisphere. The peak will be an hour or two before dawn on May 5, according to Earthsky. But this meteor shower has a "broad maximum," meaning that you can probably catch a few meteors fly by a couple of days before and after the actual peak, according to Earthsky. These meteors originate from comet 1P/Halley, and they are known for their speed, according to NASA. Because they travel so fast, about 148,000 mph (238,183 km/h), they leave behind glowing "trains" or lit up bits of debris that can streak the skies for several seconds to minutes, according to NASA.

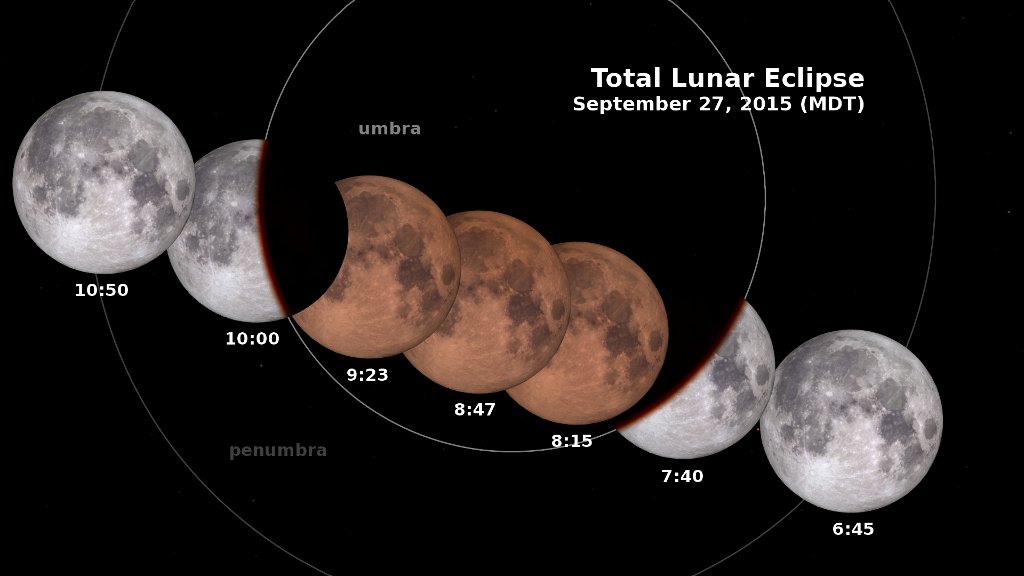

Total lunar eclipse (May)

A total lunar eclipse or "blood moon" will grace the skies on May 26, and should be visible from eastern Asia, Australia, areas across the Pacific Ocean and most of the Americas, according to Space.com and NASA. A lunar eclipse occurs when our planet's shadow blocks the sun's light from reflecting off the moon, shrouding our companion in darkness, according to Space.com. A lunar eclipse occurs only when there's a full moon; a total lunar eclipse means that Earth's shadow will completely block out the moon. A total lunar eclipse can also cause the moon to turn a copper or red color due to some light from the sun that passes through Earth's atmosphere and is bent toward the moon, according to Space.com.

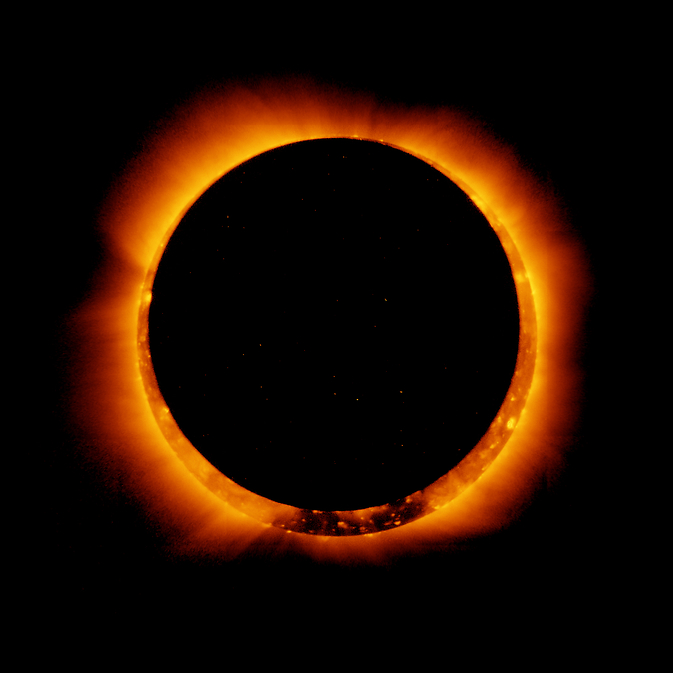

Annular solar eclipse (June)

On June 10, you might be able to see an "annular solar eclipse," which is also called a "ring of fire." This eclipse occurs when the moon passes between the sun and the Earth but doesn't completely cover the sun, creating a glowing ring (of fire) around the shadow. This particular annular eclipse will be visible only in northern Canada, Greenland and Russia, according to NASA. (Never look at the sun during a solar eclipse; looking at the sun is dangerous, according to NASA.)

Here's how to make a solar eclipse viewer so you can safely view the eclipse.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Perseid meteor shower (August)

The Perseid meteor showers are thought to be the best meteor shower of the year, according to NASA. At their peak, viewers can glimpse up to 100 meteors per hour, and they are thought to originate from the comet 109P/Swift-Tuttle. This year, the Perseids will likely peak on the night of Aug. 11 to Aug. 12, but should also be viewable the nights before and after, according to EarthSky. This meteor shower is best seen from the Northern Hemisphere in the pre-dawn hours, but can be viewed as early as 10 p.m. local time, according to NASA.

Orionid meteor shower (October)

The Orionids, known for their brightness and speed, are "considered to be one of the most beautiful showers of the year," according to NASA. These meteors, which can travel about 148,000 mph (238,183 km/h), sometimes leave behind glowing "trains." The meteors, which are thought to originate from the comet 1P/Halley are will be visible from both the Northern and Southern hemispheres after midnight, according to NASA. At its peak, viewers can see about 15 meteors per hour in a sky without a moon. But this year, a nearly full moon will likely make it difficult to see the shower, according to the Griffith Observatory. The Orionids will peak on the night of Oct. 20 to Oct. 21.

Partial lunar eclipse (November)

A partial lunar eclipse will will be viewable from the Americas, Australia and parts of Europe and Asia this November, according to Space.com and NASA. A partial lunar eclipse is one in which the Earth's shadow only partially covers the moon. This will be the second and final lunar eclipse of 2021, according to NASA. The show will begin on Nov. 19 at about 2:18 a.m. EST (07:18 UTC), peaking at 4:02 a.m. EST (09:02 UTC) and ending at 5:47 a.m. EST (10:47 UTC), according to timeanddate.com.

Geminid meteor shower (December)

The Geminid meteor shower will occur from Dec. 4 to Dec. 20. The Geminids are "usually the strongest meteor shower of the year," according to the International Meteor Organization. They will peak on the night of Dec. 13; they are best viewed at night and in pre-dawn hours and can be seen across the globe, according to NASA. The Geminid meteors tend to be bright, fast and appear yellow; in fact, they can travel about 79,000 mph (127,000 km/h). This meteor show is the "most reliable," and about 120 meteors per hour can be seen in good conditions, according to NASA.

Originally published on Live Science.

Yasemin is a staff writer at Live Science, covering health, neuroscience and biology. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Science and the San Jose Mercury News. She has a bachelor's degree in biomedical engineering from the University of Connecticut and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus