Ancient Mycenaean armor is so good, it protected users in an 11-hour battle simulation inspired by the Trojan War

Researchers recruited volunteers from the Hellenic Armed Forces to test the strength of replicas of 3,500-year-old body armor.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Body armor from the Bronze Age was strong enough to protect a Mycenaean soldier in battle 3,500 years ago, according to a new study that had 13 soldiers fight in a replica of it for 11 hours.

Researchers took a suit of armor found in 1960 by archaeologists in Dendra, a village located near what was once the ancient Greek city of Mycenae, and recruited 13 soldiers from the marines of the Hellenic Armed Forces to test the artifact's mettle, according to a study published Wednesday (May 22) in the journal PLOS One.

For decades, archaeologists have grappled with whether the armor, which includes a boar's tusk helmet and a suit consisting of bronze plates, was hardy enough for combat.

"Since its discovery, the question has remained as to whether the armor was purely for ceremonial purposes, or for use in battle," lead study author Andreas Flouris, a professor of physiology at the University of Thessaly in Greece, and his colleagues told Live Science in an email. "The Dendra armor is considered one of the oldest complete suits of armor from the European Bronze Age."

To find out, researchers equipped volunteers with replicas of the armor and weapons, including spears and stones, and had them complete an 11-hour simulation of Bronze Age warfare based off of historical accounts plucked from the pages of the Greek poet Homer's famous work "The Iliad," an epic account of roughly the last 50 days of the Trojan War.

Related: 2,800-year-old figurines unearthed at Greek temple may be offerings to Poseidon

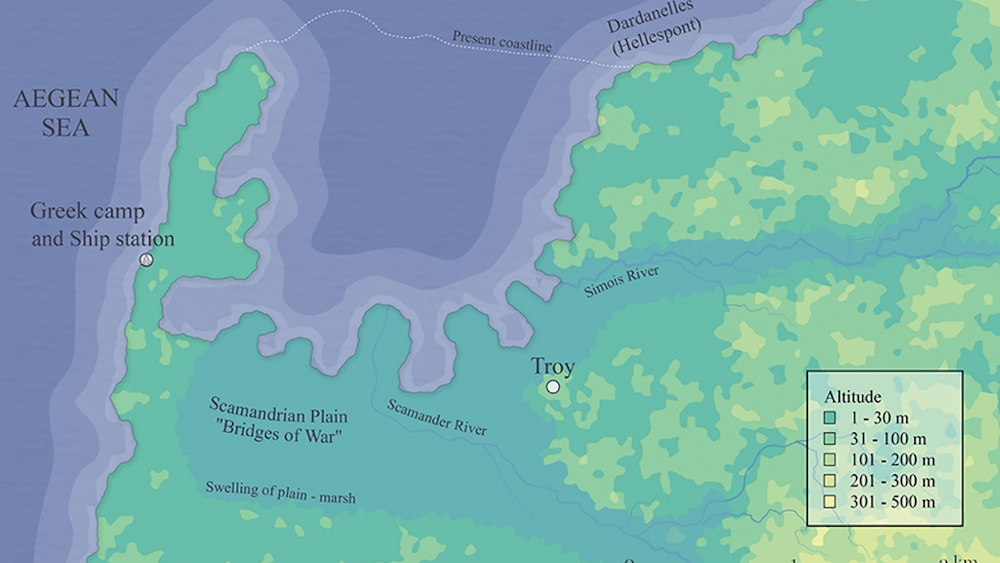

"We extracted the information needed to create a Late Bronze Age combat simulation protocol, replicating the daily activities performed by elite warriors in the Late Bronze Age," Flouris and colleagues said. "Thereafter, we used paleoclimate data to re-create the environmental conditions at the end of the Bronze Age in Troy."

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Research suggests that the temperature in this region during the Late Bronze Age would have been roughly 64 to 68 degrees Fahrenheit (18 to 20 degrees Celsius) with an annual relative humidity between 70% and 80%.

Researchers created the armor replicas using a blend of gilded metals that included copper and zinc, the closest alloy to the original bronze material. A suit followed the exact measurements of the artifact, right down to the "dimension, curvature and perforations of the original" and weighed 51 pounds (23 kilograms) once complete, according to the study.

In addition to replicating the armor, the volunteers followed diets similar to what a Mycenaean soldier would have eaten in preparation for battle, including a meal of bread, beef, goat cheese, green olives, onions and red wine.

"Interestingly, our results for blood glucose showed that the nutrition plan provided adequate energy for the volunteers during the 11-hour protocol," Flouris said.

During the trials, volunteers participated in various encounters, including duels, foot warrior versus chariot, distance encounters and chariot versus ship, according to the study. The armor didn't limit anyone's fighting ability or cause severe strain on the user, the team found.

The simulation proved to researchers that the armor would have held up in battle thousands of years ago.

"It is clear that armor of this type was suitable for use in battle, not just ceremonial," Flouris and colleagues said. "The efficacy and variety of Mycenaean swords and spears has long been recognised. The addition of 'heavy' armor will have given elite Mycenaean warriors considerable advantages over those with a shield only for defense or with the lighter 'scale' armor in use in the Middle East."

Not only that, but the Mycenaeans "were some of the best equipped" soldiers during that time period, the researchers said.

"Add the combination of armored warriors brought to battle in their chariots, and therefore arriving at the front line with full resources of energy, and these warriors must have been formidable opponents," Flouris and colleagues said.

Jennifer Nalewicki is former Live Science staff writer and Salt Lake City-based journalist whose work has been featured in The New York Times, Smithsonian Magazine, Scientific American, Popular Mechanics and more. She covers several science topics from planet Earth to paleontology and archaeology to health and culture. Prior to freelancing, Jennifer held an Editor role at Time Inc. Jennifer has a bachelor's degree in Journalism from The University of Texas at Austin.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus