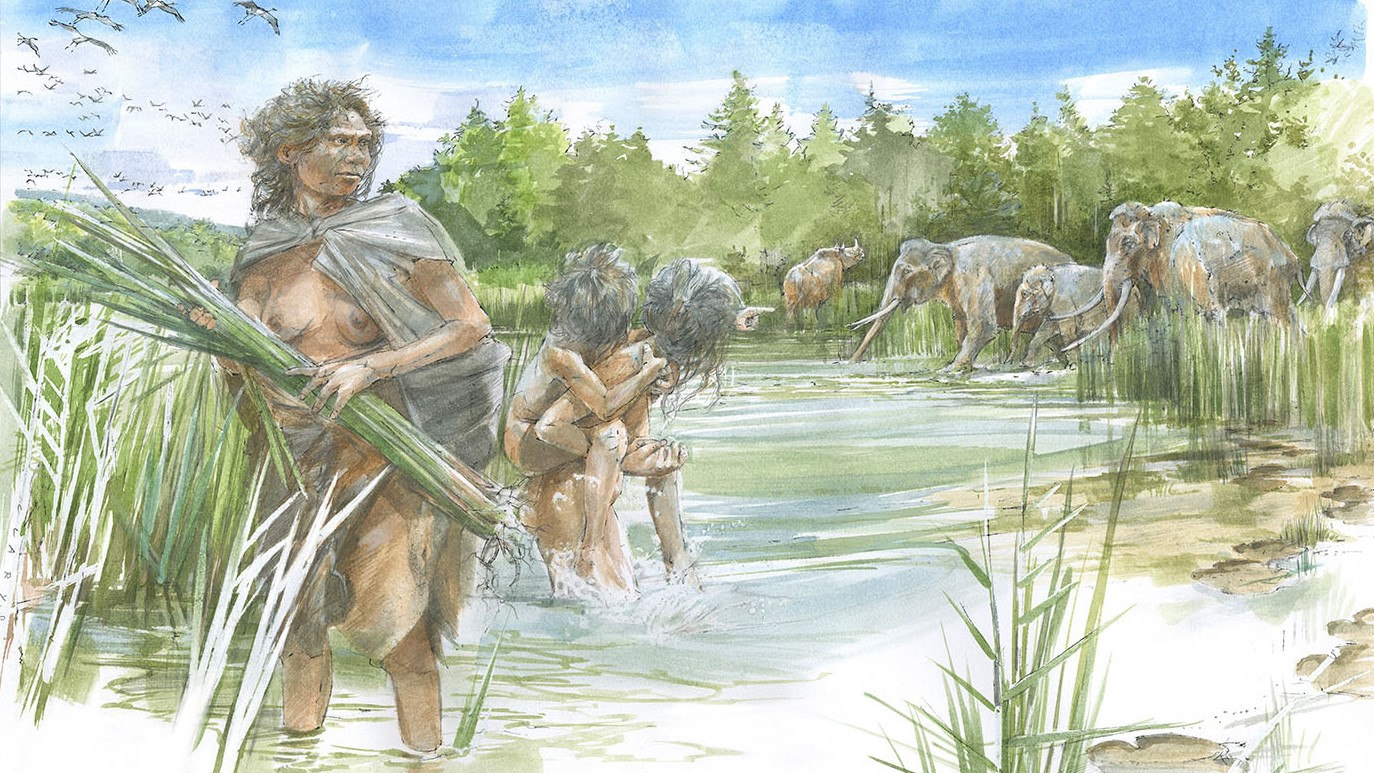

300,000-year-old footprints reveal extinct humans went on a lakeside family outing among giant elephants and rhinos

Footprints belonging to Homo heidelbergensis adults and children suggest that these human relatives foraged and played on the shores of a lake where prehistoric beasts gathered to drink.

In a forest clearing of birch and pine trees in what is today central Europe, herds of long-extinct beasts once gathered to drink on the shores of an ancient lake. Now, researchers have confirmed that early human relatives and their children foraged and bathed among them.

Three rare, 300,000-year-old footprints from a Lower Paleolithic (around 3 million to 300,000 years ago) fossil site in northwestern Germany reveal that Homo heidelbergensis, an extinct species of human that existed from about 700,000 to 200,000 years ago, co-existed with prehistoric elephants and rhinos, whose footprints were also found at the site. While a 2018 study in the journal Scientific Reports documented a similar neighborly relationship between early humans and prehistoric beasts in Ethiopia from 700,000 years ago, this is the first footprint evidence of H. heidelbergensis from Germany and only the fourth record of the species' footprints worldwide.

"These three footprints represent a significant 'direct' proof of the hominin presence on the site," Flavio Altamura, an archeologist at the University of Tübingen in Germany and lead author of a study describing the fossils, told Live Science in an email. While one footprint clearly belonged to an adult, the others were much smaller. "Since two footprints are related to young individuals, this is also proof of the existence of children on the spot," Altamura said.

The discovery is remarkable because signs of children at prehistoric sites are scarce. Most of the evidence researchers have about the earliest periods of humanity comes from tools, human remains and food waste in the form of animal bones, Altamura explained. "You have to look for children's bones, that are very rare, and it is very hard to link tools and food waste with children's activity. So it is very difficult to say something about their behavior and the kind of life they were [leading]."

The newly found footprints provide clues about what it was like to be a child 300,000 years ago. "This is a rare snapshot of childhood in prehistory," Altamura said.

The footprints reveal aspects of our human relatives' daily lives, which researchers describe in a study published May 12 in the journal Quaternary Science Reviews. The findings show that long-extinct "Heidelberg people" dwelled on the shores of an ancient lake among herds of the largest land animals at the time — prehistoric elephants called Palaeoloxodon antiquus that had straight tusks and weighed up to 13 tons (12 metric tons).

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The researchers also unearthed tracks belonging to a rhinoceros, which they identified as Stephanorhinus kirchbergensis or S. hemitoechus. They are the first footprints of either species ever found in Europe.

The human footprints were probably left during a small family outing, Altamura said. "We may suggest that a small hominin group that included children was walking among elephants and other species on the muddy shore of an ancient lake, perhaps looking for and collecting food, or bathing, or just playing there."

These are not the oldest H. heidelbergensis children’s footprints unearthed among animal prints, however. A similar collection of human footprints and animal tracks was unearthed between 2013 and 2015 at a 700,000-year-old archeological site in Ethiopia called Melka Kunture. There, a cluster of tracks belonging to 11 adults and children potentially as young as 12 months old suggested that children were present when tools were made and animals butchered.

"Children and adult footprints were found on the border of a pond where other animals congregated and where hippos were butchered by hominins, suggesting that children were assisting adults and learning since their first years how to survive in the then wild environment," Altamura, who co-authored the 2018 study of the Ethiopian fossils, said.

Sascha is a U.K.-based staff writer at Live Science. She holds a bachelor’s degree in biology from the University of Southampton in England and a master’s degree in science communication from Imperial College London. Her work has appeared in The Guardian and the health website Zoe. Besides writing, she enjoys playing tennis, bread-making and browsing second-hand shops for hidden gems.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus