Medieval Map Points to World's Richest Man, Maybe Ever

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Who is the richest person to ever have lived? Put down that Forbes Magazine — it's not Jeff Bezos.

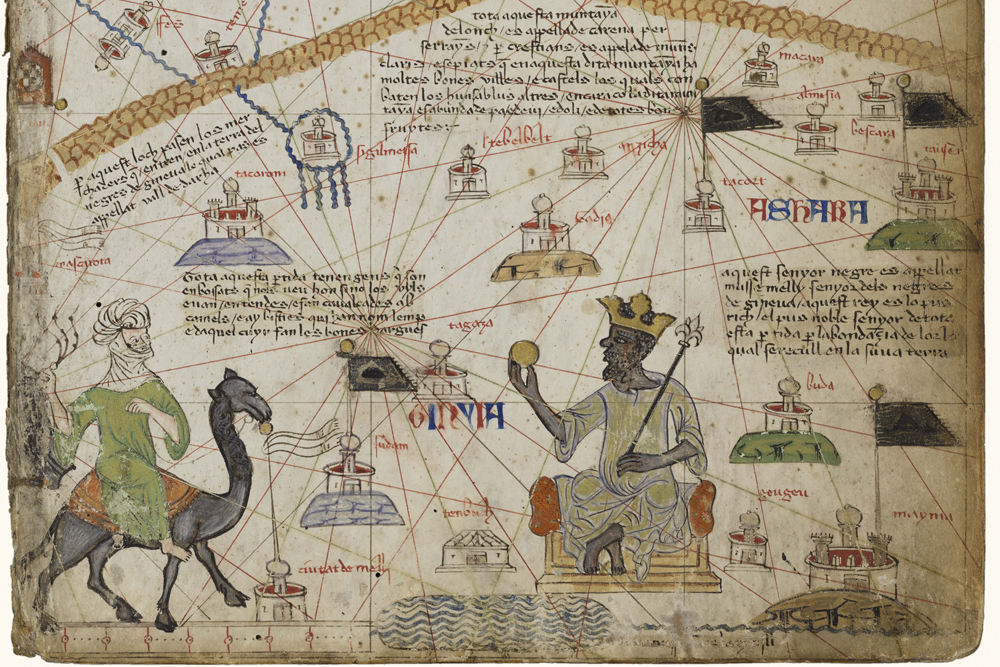

The real answer is in the pages of a Medieval manuscript, The Catalan Atlas. Centered on a page of trade routes sits a West African king holding a golden coin: Mansa Musa, the wealthiest person probably ever to walk the globe.

A reproduction of the Atlas is on display in a new exhibit, which opened Jan. 26 at the Block Museum of Art at Northwestern University in Evanston, Illinois. The exhibit, "Caravans of Gold," spotlights Africa's massive wealth and influence during the Middle Ages. The map, produced on the Mediterranean island of Majorca in 1375, contains just one example. [Cracking Codices: 10 of the Most Mysterious Ancient Manuscripts]

"Clearly, Mansa Musa and West Africa and its gold resources are of greatest importance," said Kathleen Bickford Berzock, the curator of the exhibit at the Block Museum. [Gallery: Images of Medieval African Riches]

Unimaginable wealth

The exhibit is meant to debunk stereotypes about Africa, Bickford Berzock said. While academic historians have extensively documented the importance of Africa in the Medieval world, the continent is often seen as a backwater in the public imagination. The later incursions by colonialist powers, which would strip Africa of people and resources, blotted out much of the rich culture and history that came before.

"It tells us a lot about the world we live in today to understand the long history of exchange and interaction on a global scale," Bickford Berzock told Live Science. "It also helps people think about the history of Africa before western involvement in things like the Atlantic slave trade."

Mansa Musa puts a face to the phenomenon. The ruler of the Mali empire, he had full control of the region's gold production — and Mali's gold was the purest, most sought-after gold of the day, Bickford Berzock said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"It's hard to imagine anybody having that kind of wealth today," she said, "Basically, unlimited access to wealth."

Far and wide

Other artifacts in the collection tell a similar tale. Africa was not just simply a place that Europe plundered for raw materials. It had a rich culture of sculpture, textile art and other production, Bickford Berzock said. One item in the exhibit, a seated figure found in Nigeria, was made of copper that was likely mined in Europe. Coin molds from Tadmekka, Mali, still hold flecks of the gold from the dinar coins that were a dominant form of currency of the day. The discovery of the molds confirmed Arabic texts at the time, which referred to Tadmekka as the source of dinars, Bickford Berzock said.

Trade routes snaked out from West Africa deep into sub-Saharan regions and far into East Asia and the Middle East, she said. Chinese porcelain has been found at Medieval archaeological sites in the Sahara. Ivory from Savannah elephants appears in Medieval European art. And metals, textiles, spices and more were swapped back and forth across long distances.

Some of the artistry invented in Medieval Africa survives into the modern day. On display in the new Block Museum exhibit are large biconical beads made of gold filigree. Next to an 11th-century example of one of these beads from either Egypt or Syria, Bickford Berzock and her colleagues have placed 19th- and 20th-century examples of gold-plated biconical beads, the descendants of the nearly 1,000-year-old objects made in Africa.

The exhibit is a work of cooperation between western museums and museums in Morocco, Mali and Nigeria, Bickford Berzock said. Many of the objects on display have never before left their home countries, she added.

The exhibition will remain at the Block Museum until July 21, 2019. It will then travel to Ontario's Aga Khan museum in fall of 2019 before arriving at the Smithsonian National Museum of African Art in Washington, D.C., in spring of 2020.

- 7 Bizarre Ancient Cultures That History Forgot

- 10 Biggest Historical Mysteries That Will Probably Never Be Solved

- Photos: Ancient Rock Art of Southern Africa

Originally published on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus