Medieval Germans Riddled with Tapeworms

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Sifting through preserved poop from a medieval port city in Germany, scientists discovered that the town's inhabitants were riddled with tapeworms.

The discovery also revealed a fascinating hidden record of dietary changes during that period, according to a new study. [The 10 Most Diabolical and Disgusting Parasites]

Previously, archaeological evidence has shown that that parasitic worms such as flatworms, roundworms and tapeworms — part of a group known as helminths — have been infecting people for centuries, the scientists reported.

"Humans can harbor them for years," study co-author Adrian Smith, an associate professor of zoology and infectious disease biology at the University of Oxford in the United Kingdom, told Live Science in an email. By excreting parasites' eggs, infested people helping the pests to spread, leaving a trail of egg-filled poo "wherever they go," Smith said.

"Thousands of eggs"

To understand how the parasites affected human health, Smith and his colleagues collected 152 poop samples from latrines and waste ditches at six sites in Europe, which dated from 3600 B.C. to the 17th century.

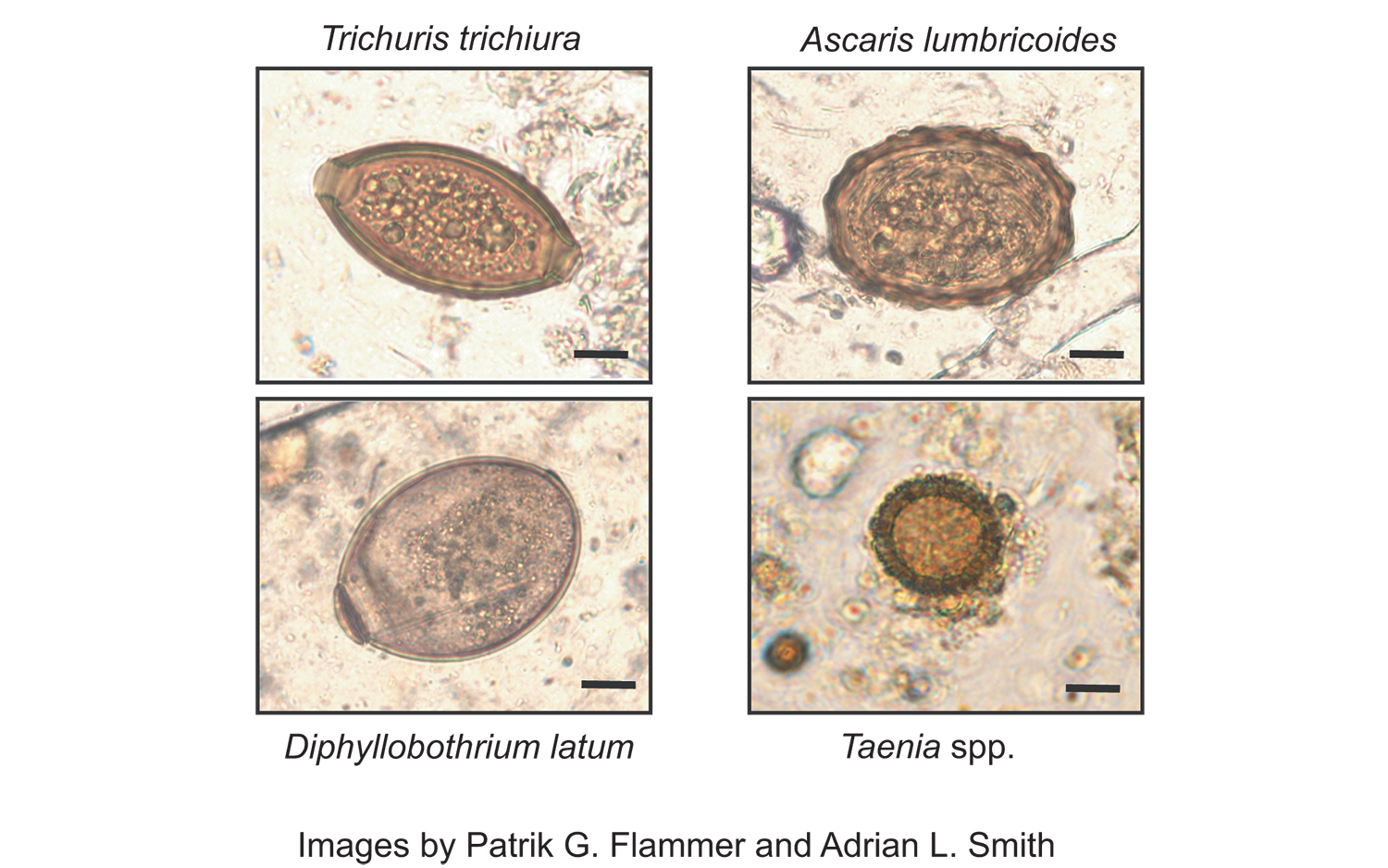

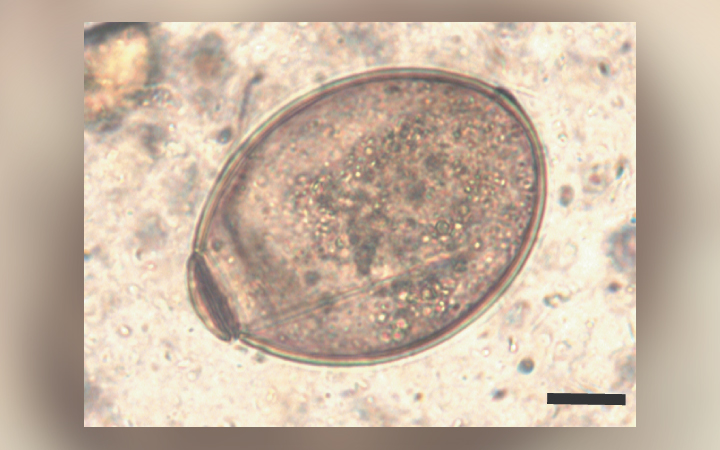

The scientists peered at preserved poo parasites through microscopes to identify the microbes' genuses and used DNA samples to confirm the species, Smith said. Parasitic nematode eggs appeared in samples from all the sites. But a group of 14th-century samples from one location — Lübeck, a medieval port city, then an important trading hub in Germany — stood out.

Fecal evidence from Lübeck contained "substantial numbers" of eggs belonging to the tapeworms Diphyllobothrium latum and Taenia saginata, which surprised the scientists, Smith said. Tapeworm eggs are typically absent or very scarce in archaeological studies of human poo; some of the Lübeck samples, however, contained hundreds or even thousands of eggs in a single gram of waste, Smith said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Tapeworms are typically transmitted to people when they eat undercooked fish or red meat, Smith explained. The worms in the Lübeck samples became much more common beginning in the 1300s, which suggests a significant change in the local diet, likely one that increased people's consumption of meat or fish, Smith said.

The early 1300s also brought industrial changes to Lübeck that may have affected the life cycle of D. latum, a tapeworm found in fish, Smith told Live Science. Growing numbers of tanneries and butcher shops may have polluted rivers where fish infected with D. latum lived, driving changes in the parasite that made human hosts more attractive, he said.

The researchers' discovery provides compelling clues about the livelihoods and health of medieval people, their levels of sanitation, "and, as seen with the tapeworms, dietary preferences," Smith said in the email.

"We have only begun to scratch the surface of how useful parasites might be" in archaeology, he said.

The findings were published online Oct. 3 in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B.

Originally publishedon Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is a science journalist and author of "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind-Control" (Hopkins Press). She formerly edited for Scholastic and was a channel editor and senior writer for Live Science. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to LS, she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in NYC. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post, How It Works Magazine and CNN.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus