Traces of the World's First 'Microbrew' Found in a Cave in Israel

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

The world's oldest beer may have been brewed for a funeral 13,000 years ago.

At a graveyard cave in Israel, archaeologists discovered traces of mashed wheat and barley lining pits carved into the bedrock. The researchers interpreted these residues as leftovers from beer brewing, perhaps part of a funerary feast.

"This accounts for the oldest record of man-made alcohol in the world," Li Liu, a professor of Chinese archaeology at Stanford University, said in a news release.

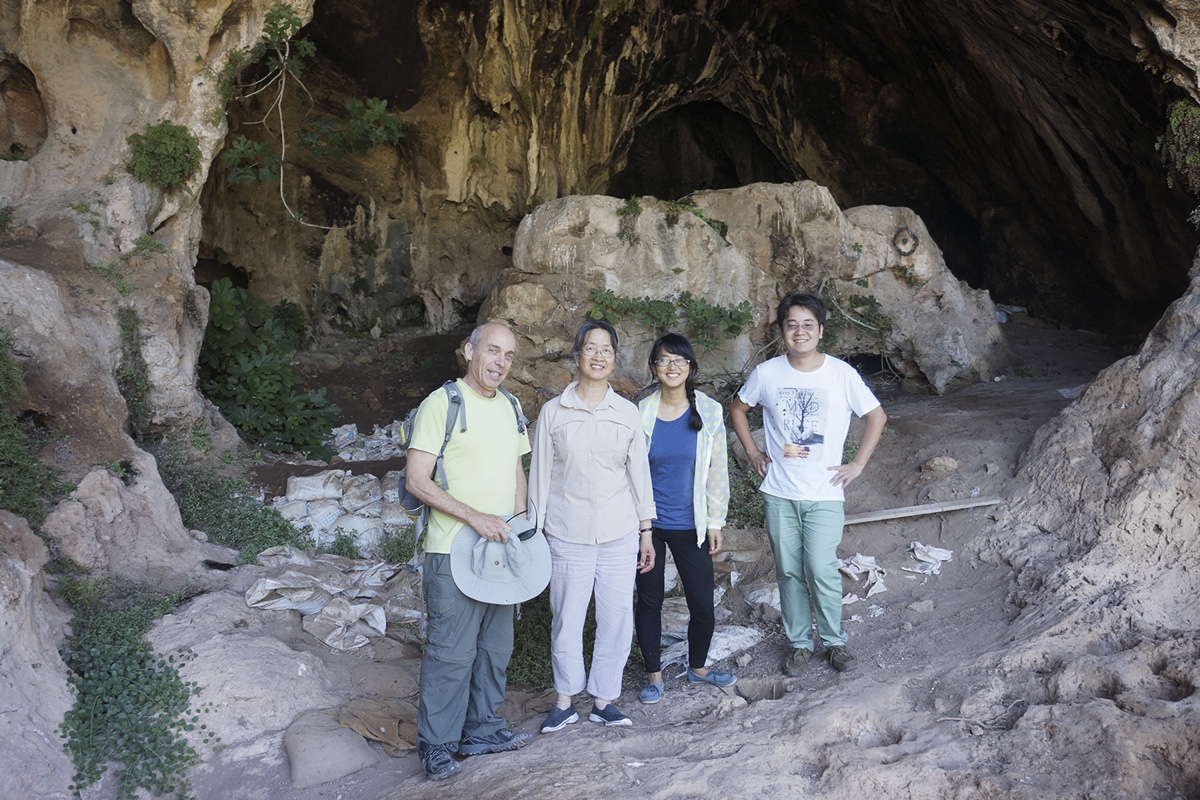

Liu's team had been trying to learn about ancient diets from plant residues on the stone pits found in the Raqefet Cave, a Natufian grave site near Haifa, Israel. [Raise Your Glass: 10 Intoxicating Beer Facts]

The Natufians were a Stone Age culture that lived in the Near East from around 15,000 to 11,500 years ago. They established some of the earliest settlements in the world and may have been among the earliest people to domesticate plants and animals.

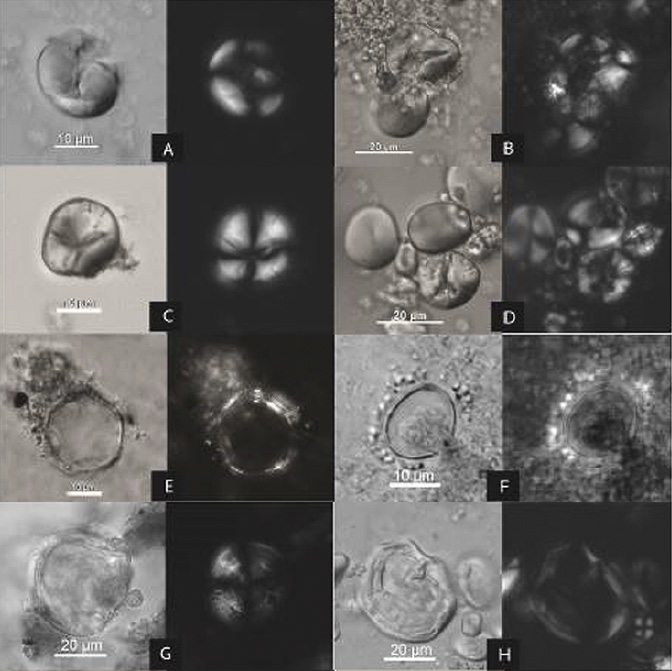

At Raqefet Cave, Liu's team collected residue samples from the stone pits, or mortars that had been dug into the cave. Under a microscope, they saw damaged-looking starch granules, thought to be from wheat or barley that was malted and mashed during beer brewing.

To test this hypothesis, the researchers conducted experiments to look at how starch granules transformed during the brewing process. To re-create Natufian-style beer, they turned barley into malt, which they mashed and heated and left to ferment with yeast. Under the microscope, the modern starch granules matched the ones found at Raqefet Cave, Liu and her colleagues reported in the Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"I thought [the study] was pretty exemplary in terms of the procedures and techniques," said Brian Hayden, an archaeologist at Simon Fraser University in Canada who was not involved in the study, but reviewed the paper before publication. "They show that in the brewing process, the starch grains undergo some morphological changes."

Hayden told Live Science that there has been considerable debate among archaeologists about the nature of the Natufian culture and other complex hunters and gathers of the same period. He's argued that this was a society with surpluses, wealth, social inequality and extensive trade networks —and finding evidence for brewing helps support that point of view.

"Brewing by itself indicates that this is a society with surpluses," Hayden told Live Science. "A lot of the residual material from brewing is discarded."

He added that there is evidence for feasting in the Natufian culture, and ethnographic evidence suggests that feasting for many traditional societies involves making alcohol.

"We were predicting that eventually somebody would find the smoking brew pot and demonstrate that there was brewing in the Natufian," Hayden said.

Pat McGovern, a biomolecular archaeologist at the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, has also been waiting for evidence of alcohol consumption from the Paleolithic period, or Old Stone Age, which he calls the "Holy Grail" in his book "Ancient Brews" (W. W. Norton & Co., 2017).

"The earliest evidence we had for ancient beverages until now was from the Neolithic period," McGovern told Live Science. "I believe that this article is on the right track in finding out more about fermented beverages during 99 percent of humankind's history, dating back millions of years."

McGovern does, however, think the starch analysis could be strengthened by further chemical and pollen studies. "It would be good to have additional verification by different methods of the ingredients that were used, and of the mashing or fermentation process," he said. "I'm not totally convinced, but I think it was highly probable that people were making a fermented beverage in this period, and that it was used for religious burial practices."

The findings at Raqefet Cave might also add to the debate over whether a thirst for beer or a hunger for bread may have driven people to domesticate grain. In July, another group of archaeologists working at a Natufian site in east Jordan reported that they found the earliest evidence of bread making — 14,000-year-old traces of charred flatbread made from wild grain.

Original article on Live Science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus