Einstein's Crude, Racist Travel Diaries Have Been Published in English

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

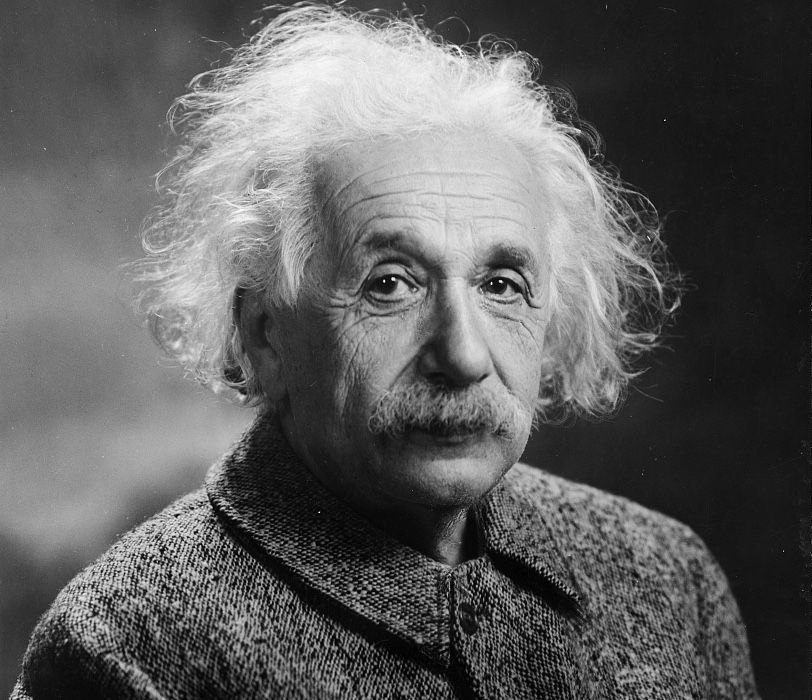

Albert Einstein, the most important physicist of the modern era and a man who famously attacked American racist ideologies, wrote down detailed, racist ideas about people from China, Japan, Sri Lanka and India.

The physicist wrote these thoughts in his travel diaries while visiting Asia between October 1922 and March 1923. German speakers have had access to the travel diaries for a long time as part of a larger collection of Einstein's personal writings, but the writings were recently published in English for the first time by the Princeton University Press. They complicate the picture of Einstein, who was the best known of the many Jewish scientists who left Nazi Germany as refugees in the early 1930s, as an anti-racist and advocate for human rights.

As reported by Smithsonian magazine, Einstein publicly aligned himself with the values of the U.S. civil rights movement. In 1931, while still in Germany, he submitted an essay to the famous black sociologist, anti-capitalist and anti-racist writer W.E.B. Du Bois' magazine The Crisis. Later, during a speech at Lincoln University in Pennsylvania, he said, "There is separation of colored people from white people in the United States. It is a disease of white people. I do not intend to be quiet about it."

Einstein's personal writing in the early 1920s, however, did not reveal that anti-racist spirit. Very much a grown man in his mid-40s and already a famous Nobel Prize winner for his work on the photoelectric effect, Einstein wrote of people from China (as reported in The Guardian) that, "even those reduced to working like horses never give the impression of conscious suffering. A peculiar herd-like nation... often more like automatons than people."

Later, he added, "I noticed how little difference there is between men and women; I don't understand what kind of fatal attraction Chinese women possess which enthrals the corresponding men to such an extent that they are incapable of defending themselves against the formidable blessing of offspring."

Einstein's comments on people from India and Sri Lanka were similarly demeaning, while he jotted down less-nasty but nonetheless racist and borderline eugenic thoughts about those from Japan.

"Pure souls as nowhere else among people. One has to love and admire this country," he wrote of Japan, but later added, "Intellectual needs of this nation seem to be weaker than their artistic ones — natural disposition?"

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

It might be tempting to ascribe Einstein's racist writing to the norms of the era within which he wrote, but his expressed views — views that unscientifically assume deep, biologically rooted intellectual differences among races — were not universal at the time.

Franz Boas, a scientific anthropologist and older contemporary of Einstein who moved from Germany to the United States in 1899 (also to become a professor in the Ivy League, at Columbia University), wrote extensive critiques of the pop-pseudoscience of "scientific racism." Boas' work revealed the unscientific methods underpinning eugenic claims of sharp divisions among races.

Du Bois, who Einstein later corresponded with, similarly used rigorous scientific tools to debunk so-called "scientific racism."

Einstein, despite his public comments on the issue, clearly missed the scientific memo.

Originally published on Live Science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus