Underground Castles? How Desert Spiders Craft Vertical Tunnels

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Beachgoing sandcastle builders know the exquisite frustration of tunneling into sand that's too dry. The tunnel simply won't hold its shape and quickly collapses.

But some types of desert spiders have mastered the technique of working with dry sand, excavating subterranean burrows — a few grains of sand at a time — that somehow retain their form and withstand pressures from wind and the shifting weight of the sand around them.

In a new study, scientists closely observed four species of desert spiders known to excavate vertical sand tunnels for hiding, resting and breeding, in order to dig up their engineering secrets. Unexpectedly, the researchers discovered that the arachnids used different yet equally effective methods for collecting and moving sand while they worked, and they strengthened the tunnels as they dug with carefully laid supporting layers of silk webbing. [Photos: Modeling Scorpions' Lairs in 3D]

Burrow-dwelling spiders like those in the study are strictly nocturnal. For the scientists, that meant spending long hours crouched in sandy environments with a flashlight, the study's lead author Rainer Foelix, an arachnologist at the Neue Kantonsschule Aarau in Switzerland, told Live Science in an email.

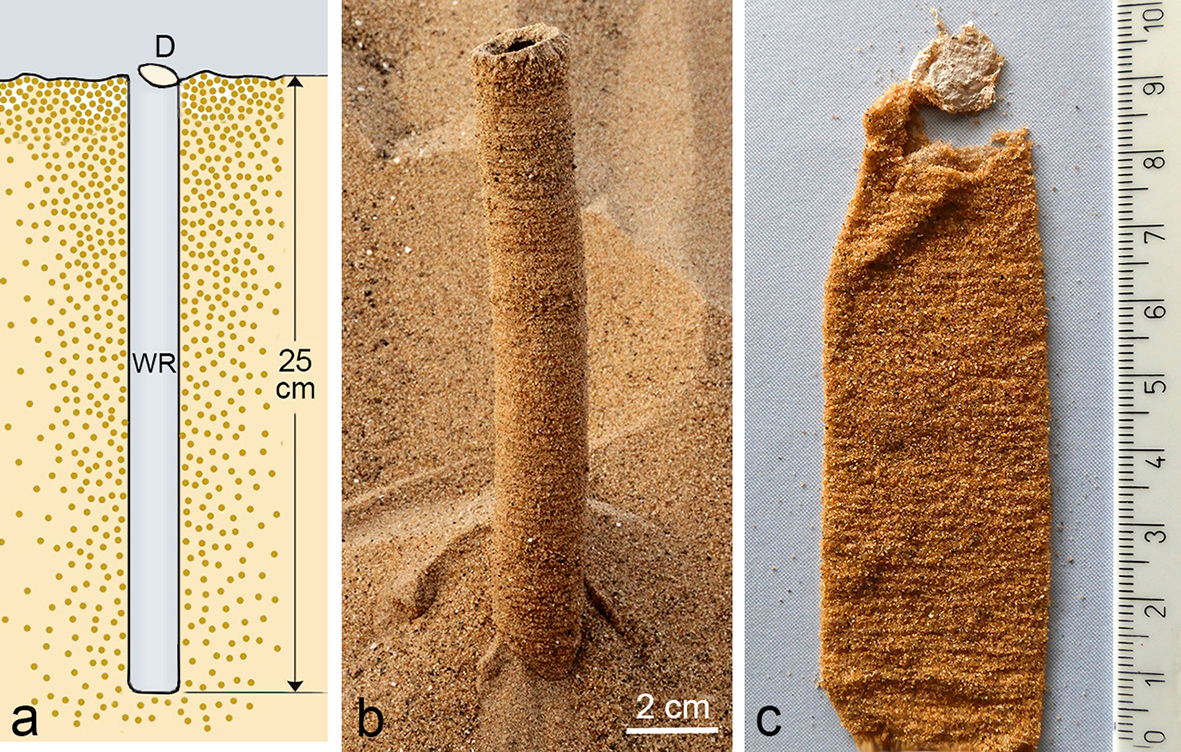

One of the spider species — Cebrennus rechenbergi, which is native to the deserts of northern Morocco — is also known as the cartwheeling spider for the unusual rolling locomotion that it uses when threatened. It has a body length of about 0.8 inches (2 centimeters), and digs burrows measuring about 10 inches (25 cm) deep and around 0.8 inches in diameter. When study co-author Ingo Rechenberg, a professor at the Technische Universität Berlin (Technical University of Berlin) and the scientist who discovered and named the spider, observed how these spiders worked, he noted that they built their tunnels "like people build a well," Foelix told Live Science.

First, the C. rechenbergi spider excavated a hole on the surface; then it added a stabilizing ring of silk, in the same way a human well builder would add a tin sheet to hold the walls of the hole in place. Once the walls of a tunnel section were secured, the spider would remove another layer of sand and soil, moving farther down and reinforcing the walls as it went, the study authors reported.

"Rechenberg watched carefully and noticed that a spider has to make about 800 runs to carry a small load of sand aboveground" — a task that took the spider about 2 hours to finish, Foelix said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

But how did the spiders remove so much sand? It turned out that different species of burrow-digging spiders used very different methods, according to the study.

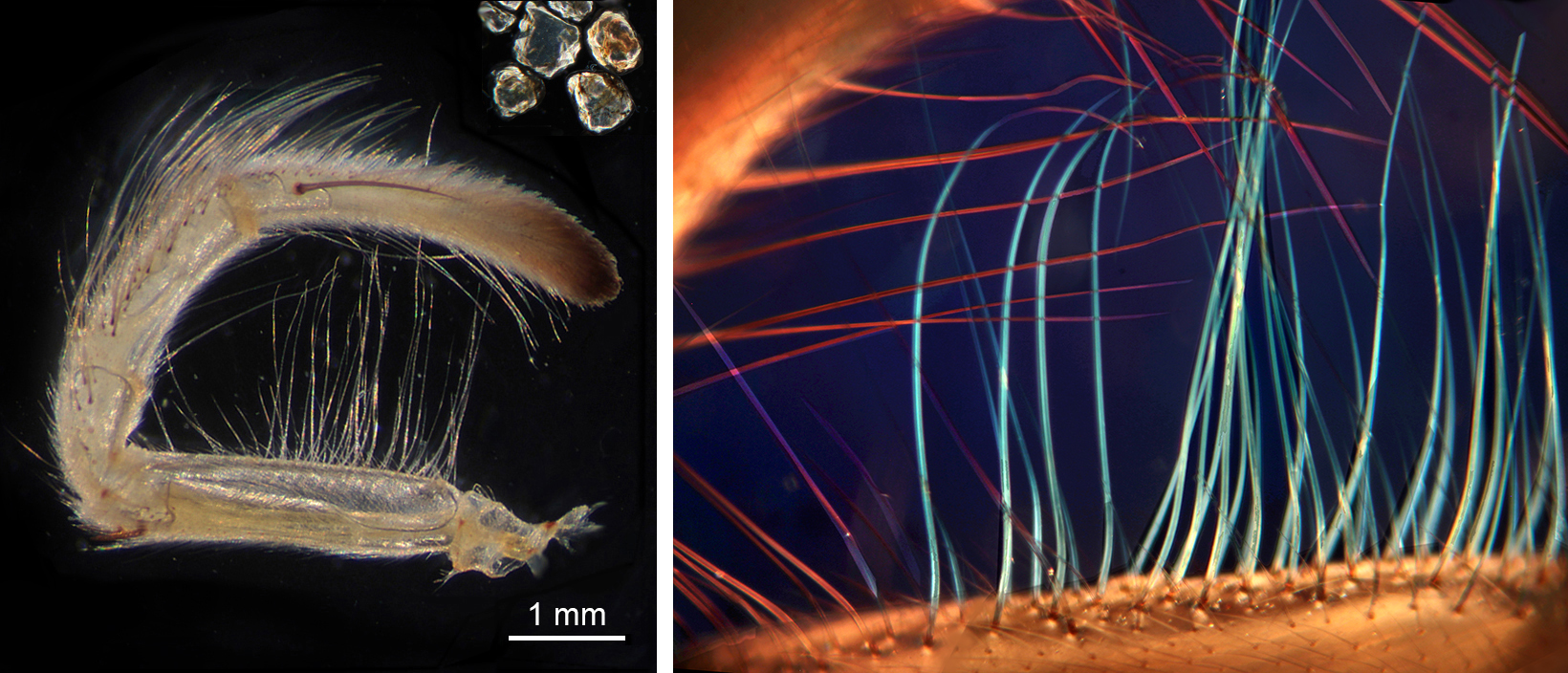

C. rechenbergi relied on long bristles fringing its pedipalps and chelicerae — appendages that frame its head and mouth — to carry sand out of its growing tunnel. Some of the bristles grow at right angles to other tiny hairs, forming a type of mesh basket that contains arid sand even when there's nothing else holding grains together. In fact, the tiny piles of sand that the spider discarded from these "baskets" disintegrated immediately once the arachnid released them, the scientists wrote in the study.

However, the wolf spider Evippomma rechenbergi — also discovered and named by Rechenberg — which inhabits the same desert environment as C. rechenbergi, lacks the specialized bristles of its neighbor. When the scientists carefully inspected clumps of sand left at the mouth of the wolf spider's burrow, they detected strands of silk binding the sand together, to make it easier to carry.

Another type of wolf spider, Geolycosa missouriensis, found in North America, was known from prior research to transport solid pellets of sand. But it did not appear to bind them with silk, perhaps relying on surface moisture to hold the sand grains together. However, as the researchers gathered their data about this spider from previous studies, they could not say for sure what technique the spiders used to consolidate their sand bundles.

The variety of sand-moving methods demonstrated by the spiders — using a hairy "carrying basket," blending sand with silk or clumping sand grains together — showed that these tiny builders are capable of finding unique construction solutions to address similar environmental challenges, Foelix told Live Science.

In fact, the researchers were surprised to see that spiders living in the same ecosystem practiced such diverse techniques for achieving the same goal, he said. And considering there are other types of tunnel-digging spiders — as well as ants and wasps — there are likely even more practices that these industrious insect engineers are putting to work, which are yet to be discovered, Foelix said.

"Certainly, many more species need to be inspected," he added.

The findings were published online Dec. 11 in the Journal of Arachnology.

Original article on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is a science journalist and author of "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind-Control" (Hopkins Press). She formerly edited for Scholastic and was a channel editor and senior writer for Live Science. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to LS, she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in NYC. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post, How It Works Magazine and CNN.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus