Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Scientists searching for signs of intelligent extraterrestrial life should put themselves in the aliens' shoes, a new study suggests.

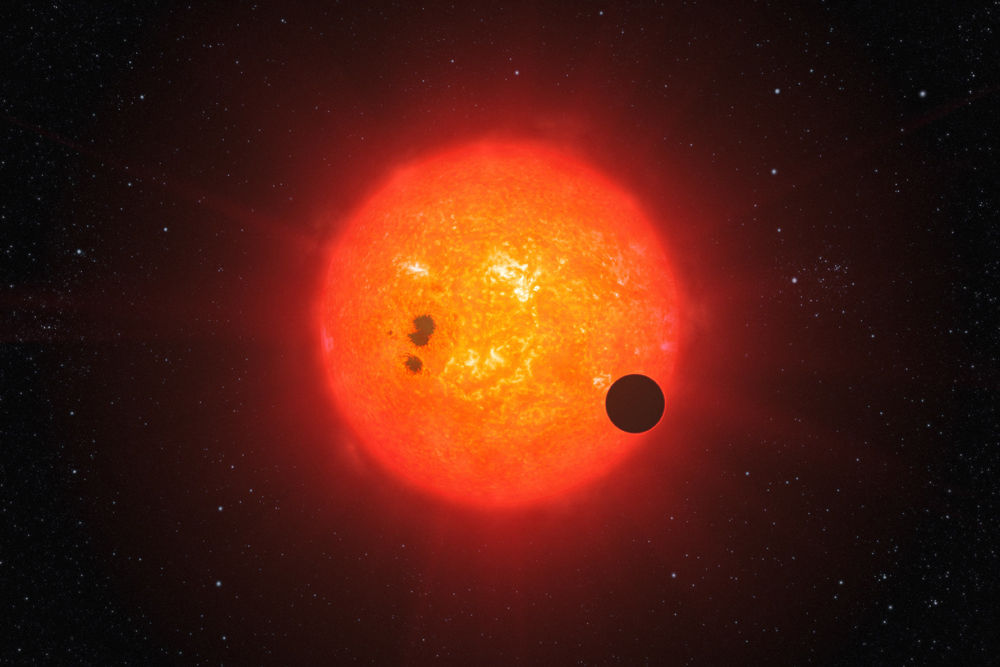

Researchers have identified and characterized many potentially habitable alien planets via the "transit method," which notes how parent stars' light changes when orbiting worlds cross these stars' faces from Earth's perspective. (NASA's Kepler space telescope is the most famous and prolific instrument to use this technique.)

Intelligent aliens could theoretically use this same strategy to discover Earth, and to determine that it has the ability to support life, scientists said. [13 Ways to Contact Intelligent Aliens]

"It's impossible to predict whether extraterrestrials use the same observational techniques as we do," study lead author René Heller, of the Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research in Germany, said in a statement. "But they will have to deal with the same physical principles as we do, and Earth's solar transits are an obvious method to detect us."

Advanced aliens who have made such a detection might try to send Earth a message to get in touch, the reasoning goes.

But cosmic geometry dictates that Earth's solar transits are visible from a limited swath of the sky — a sliver Heller and co-author Ralph Pudritz, a professor of physics and astronomy at McMaster University in Canada, dub the "transit zone."

The search for extraterrestrial intelligence (SETI) — including projects such as the recently launched Breakthrough Listen Initiative — should therefore focus on the transit zone, Heller and Pudritz wrote in the new study, which will be published in the journal Astrobiology.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The transit zone contains about 100,000 stars, according to the researchers, so there's no shortage of potential targets for SETI scientists' radio telescopes. (Observations by Kepler and other instruments suggest that every Milky Way star hosts at least one planet on average, and many of these worlds orbit in the "habitable zone" — the range of distances from a host star where water may exist in liquid form on a planet's surface.)

"If any of these planets host intelligent observers, they could have identified Earth as a habitable, even as a living world long ago, and we could be receiving their broadcasts today," Heller and Pudritz wrote in the new study.

To date, researchers have discovered about 2,000 confirmed exoplanets; Kepler is responsible for more than half of these finds.

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus