In Photos: Clever Chameleons Stick Out Their Tongues

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Chameleons are known for their color-changing trickery and tongue-lashing feats. Now, scientists have found the tiniest of these clever reptiles also pack the most power in their elastic tongues. Here's a look at the amazing animals and their tongue-y feats. [Read full article on tiny chameleons]

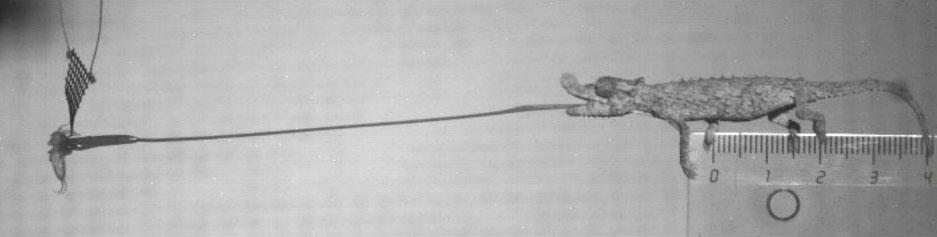

Tiny but mighty

A tiny Rhampholeon spinosus chameleon snags a cricket with its tongue. New research published January 4 in the journal Scientific Reports finds that these chameleons can accelerate their tongues at 264 times the force of gravity. (Photo Credit: © Christopher Anderson)

Titanic tongues

A Parson's chameleon (Calumma parsonii parsonii). Brown University research Christopher Anderson used high-speed video to record this species capturing a cricket with its tongue. He recorded a male Parson's chameleon 7.5 inches long (19 centimeters) flicking its tongue out 6.7 inches (17.1 centimeters), nearly its entire body length. Some chameleons can extend their tongues up to 2.5 body lengths from their mouths. (Photo Credit: © Christopher Anderson)

Madagascar leaf chameleon

Brookesia supercillaris, the Madagascar leaf chameleon. In a test of a 1.8-inch-long (4.5 centimeter) chameleon of this species, researchers found that the animal could extend its tongue at least 3.5 in. (9 cm), reaching a peak acceleration of 4.9 meters per second (11 mph). (Photo Credit: © Christopher Anderson)

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Tongue in action

A screenshot from a high-speed video of Trioceros hoehnelii, or von Höhnel's chameleon, snagging a cricket. These chameleons grow to about 10 inches (25 cm) long. To project their tongues in the blink of an eye, chameleons use bone, muscle and connective tissue. The tongue attaches to the hyoid bone, around which a tubular sheath of muscle wraps. When this tubular muscle contracts, it stretches connective tissue between the muscle and the bone. Like a stretched rubber band, this tissue recoils dramatically when let go, enabling a massively powerful tongue acceleration. (Photo Credit: © Christopher Anderson)

Tiny hunters

Triceros hoehnelii prepares to chow down on its cricket quarry. Pound-for-pound, small animals have higher metabolic needs than larger animals. Fortunately, smaller chameleons can shoot their tongues out farther and accelerate them faster than their larger cousins, helping them hunt effectively. (Photo Credit: © Christopher Anderson)

What a cutie!

A baby Tricoceros hoehnelii at less than a day old. This species calls eastern Africa home. (Photo Credit: © Christopher Anderson)

Champion chameleon

What a big nose you have! A male Kinyongia fischeri, or Fischer's two-horned chameleon, perches on a branch. In the lab, a 4.7-inch-long (12 cm) individual of this species shot its tongue out 2 inches longer than its body length, or a distance of 6.7 inches (17.1 cm). (Photo Credit: © Christopher Anderson)

Becoming a mama

A Triceros montium, or Cameroon mountain two-horned chameleon, lays eggs. Among amniotes (reptiles, mammals and birds that lay eggs on land or keep them in the female's body), chameleons have the highest capacity for explosive power. Their tongues release energy at a rate of up to 14,000 watts per kilogram, thanks to their elastic tissues. In comparison, the peak power seen in vertebrate muscles is 1,100 watts per kilogram in the beating wing of a quail. Only some species of salamanders have more impressive tongues than the smallest chameleons. (Photo Credit: © Christopher Anderson)

A Madagascar native

Furcifer lateralis, a chameleon species found only in Madagascar. These colorful chameleons grow up to about 10 inches (25 cm) in length and can change colors from dark to light. (Photo Credit: © Christopher Anderson)

Losing ground

Trioceros montium, a colorful chameleon species found in Cameroon. In one experiment, a 4-inch-long (11 cm) individual of this species stuck its tongue out 5.3 inches (13.5 cm) in pursuit of a cricket meal. This beautiful species is listed as "near threatened" by the International Union for Conservation of Nature, because it is losing habitat and possibly being over-collected for the international pet trade. (Photo Credit: © Christopher Anderson)

Follow Stephanie Pappas on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus